History of Eswatini facts for kids

The Kingdom of Eswatini, also known as Swaziland, has a long and interesting history. People have lived here since the early Stone Age. The first known people were hunter-gatherers called Khoisan. Later, many Nguni people settled in the area. They came during the great Bantu migrations. People speaking languages like modern Sotho and Nguni arrived by the 11th century. The country gets its name from King Mswati II. He was a powerful king who expanded the country's size. Today, the people of Eswatini belong to different clans. These clans are grouped by when and how they settled in the country.

Contents

Early Settlements in Eswatini (Before 1700s)

The first people known to live in this region were Khoisan hunter-gatherers. Later, many Bantu groups moved into the area. These groups came from the Great Lakes regions of eastern and central Africa. We know that farming and iron use started around the 4th century. People speaking languages related to Sotho and Nguni settled here by the 11th century.

The Swazi settlers were once known as the Ngwane people. Before coming to Eswatini, they lived near the Pongola River. Before that, they were near the Tembe River, close to modern-day Maputo. King Dlamini III led the Swazi people from about 1720 to 1744. He was the father of Ngwane III. Ngwane III was the first king of modern Swaziland.

Conflicts with the Ndwandwe people forced the Swazi to move north. Ngwane III set up his capital at Shiselweni. Later, under King Sobhuza I, the Ngwane people moved their capital to Zombodze. This is in the heart of present-day Eswatini. As they moved, they included older clans into their nation. These clans are known as the Emakhandzambili.

Building the Swazi Nation (1740s–1868)

Under Ngwane III, the Swazi people settled in what is now Eswatini. They first settled north of the Pongola River. The Ngwane Kingdom was formed during Ngwane III's rule, from about 1745 to 1780. The early Swazi people moved from the Lubombo mountains to the Pongola River banks.

King Ngwane III set up Swazi settlements near the Ndwandwe Kingdom. The Swazis often had conflicts with their Ndwandwe neighbors. Ngwane III's capital was in southern Eswatini, at Shiselweni. This was near Nhlangano and Mahamba.

The Swazis created a kingdom with a king and Queen Mothers. If a crown prince was too young, a Queen Regent would rule. When Ngwane died, LaYaka Ndwandwe became Queen Regent. She ruled until Ndvungunye became king. King Ndvungunye ruled from 1780 until 1815. He was followed by Ngwane IV, after Queen Regent Lomvula Mndzebele's rule.

Ngwane IV was also known as Sobhuza I and Somhlolo. He was a respected king of Swaziland. Sobhuza continued to expand the country's territory.

The conflict between Swaziland and the Ndwandwe kingdom led Somhlolo (Sobhuza I) to move his capital. He moved it from Shiselweni to Zombodze, in the center of Eswatini. Somhlolo became king in 1815. He brought the Emakhandzambili clans into his kingdom. This added to the Bemdzabuko, or "true Swazi" people.

Somhlolo was a smart leader from 1815 to 1839. This period included the Mfecane period. This was when Shaka Zulu created his powerful kingdom. Sobhuza used his diplomatic skills to avoid fighting Shaka. He made alliances when it helped him. Because of this, Eswatini was not affected by the Mfecane wars.

In 1839, Somhlolo was followed by his son, Mswati II. Mswati II is known as the greatest of the Swazi fighting kings.

Mswati inherited a large area. It stretched north to present-day Barberton. It also included the Nomahasha district in Mozambique. Mswati kept expanding Swazi territory. The clans added during his rule were called Emafikamuva. During his reign, the territory grew northward. His capital was at Hhohho in northern Eswatini.

Mswati also improved the military organization of his regiments. His own regiment was called Inyatsi. He performed the sacred incwala ceremony at Hhohho. This was different from his predecessors who used the Ezulwini valley. Mswati was a strong king. He attacked other African tribes to get cattle and captives. Within Eswatini, he used his power to limit the Emakhandzambili chiefs.

Mswati made land grants to the Lydenburg Republic in 1855. However, the details of this sale were not clear. The Boers were not very strong then and could not fully use the land. Mswati continued to fight other African tribes. He fought in areas like Zoutpansberg and Ohrigstad. His death in 1865 ended the conquests by Swazi kings.

Mswati was to be followed by Ludvonga. However, Ludvonga died young. So, the Swazi National Council chose Mbandzeni instead. King Mbandzeni appointed Chief Manzini Mbokane as a main tribal advisor. Chief Manzini Mbokane was a leader of the King's Advisory Council, later called Liqoqo.

European Influence and Concessions (1868–1899)

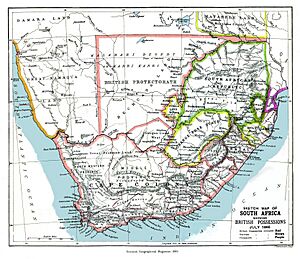

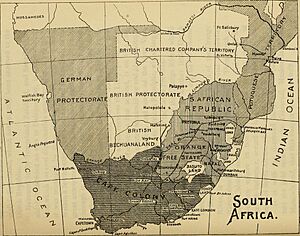

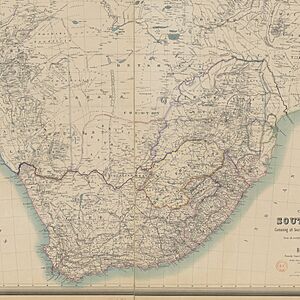

The independence of the Emaswati people was affected by British and Dutch rule. This happened in Southern Africa during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1881, the British government signed an agreement. It recognized Swazi independence. But in 1894, another agreement placed Swaziland under the South African Republic as a protectorate.

Swazi people first met Europeans when Dutch Trekboers arrived in the 1840s. By 1845, about 300 Boer families had settled in Ohristad and Lydenburg. Two sales documents from 1846 and 1855 show the sale of Swazi land to the Dutch republics. This was for 170 cattle. These documents seemed to give all Swazi territory to the Dutch.

After King Mswati II died in 1865, Queen Regent Tsandzile Ndwandwe ruled until 1875. In 1868, the South African Republic tried to take over Swaziland. Mbandzeni was chosen as crown prince after his half-brother Ludvonga died in 1872. There were threats from Prince Mbilini, a rival for the throne. Mbilini was allied with the Zulu King Cetshwayo. However, Mbilini was not successful.

The British stopped any attacks from Cetshwayo. The Transvaal Boers also wanted to show their power over Swaziland by supporting Mbandzeni. In 1879, the same year as the Zulu war, Mbandzeni helped the British. The British were then controlling the Transvaal. He helped them defeat Sekhukhune and break up his kingdom. In return, Swaziland's independence was promised forever. It would be protected from Boer and Zulu attacks.

In 1881, the Pretoria Convention recognized British control over the Transvaal State. Article 24 of this agreement guaranteed the independence of Swaziland. It also recognized its borders and the Swazi people in their country. However, this agreement reduced the size of Swazi territory. Some Swazi people became residents of the Transvaal territory.

The London Convention of 1884 also recognized Swaziland as an independent country. Mbandzeni was its King. But between 1885 and 1889, more land deals were made. The number of Europeans in Swaziland grew. Mbandzeni became worried about some of these deals. He asked for British help. Boer movements into Swaziland also increased these requests. The situation in the country got worse. There were raids, cattle theft, and children being taken from Swazi villages by Boers. Britain refused to get involved. They said there were too many non-British Europeans and that the South African Republic held too many concessions.

After Mbandzeni's death in 1889, the Swazi Government made a statement. Queen Regent Tibati Nkambule and the Swazi Council appointed Sir Theophilus Shepstone. They also appointed Chief Ntengu Mbokane and two other officers. These officers represented the South African Republic and Britain. A temporary council was set up to manage the country. This included dealing with land deals and European residents. A special court was created to check which land deals were valid.

The London Convention of 1894 finalized the situation for Swaziland. The Swazi proclamation supporting this convention was signed in December 1894. This convention recognized the status of Swaziland, its people, and its kings. However, for administrative matters, Swaziland would be a protected state of the Transvaal republic. This came with guarantees for the rights of Swazi people and their government system. This administration lasted until the Anglo-Boer War began in 1899.

Ngwane V became crown prince after Mbandzeni's death in 1889. He was crowned in 1895. In 1898, he was accused of causing the deaths of his advisors. He fled to British Zululand but returned after his safety was guaranteed. He was charged with a lesser crime and fined. His judicial powers were also reduced. In October 1899, the Anglo-Boer War started. This ended the Transvaal's control over Swaziland. King Ngwane V ruled until December of that year. He died while dancing the sacred incwala.

The Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902)

Eswatini was involved in the Second Boer War (1899–1902). At the start of the war, the South African Republic governed Eswatini. The main colonial office was in Bremersdorp (now Manzini). In September 1899, colonists started leaving the area. King Ngwane V (Bhunu) was told that he would be in charge while the White residents were away.

On October 4, 1899, an official notice was issued for all White inhabitants to leave. Most British people were taken to the border with Mozambique. Other South African civilians went to different places. People with dual nationality were still expected to fight. Many of them escaped to Mozambique or the Colony of Natal.

Soon, Swaziland forces were involved in small fights. On October 28, 1899, a new Swaziland Commando unit attacked a British police post. The South African unit had about 200 men, while the outpost had only 20. King Bhunu warned the police post of the attack. The police retreated. The Commandos burned the abandoned post and a nearby shop. Then they burned another village.

Meanwhile, the Swazi people had been told to stay calm and not join the war. But King Bhunu felt free from colonial control for the first time. He started to settle old disagreements with political rivals. News of some violent deaths reached the Boer forces. King Bhunu was striking against anyone he suspected of wrongdoing. On December 10, 1899, King Bhunu died from a serious illness.

His mother, Labotsibeni Mdluli, became regent. She began to remove the remaining advisors and favorites of Bhunu.

Swazi regiments moved around the country during these internal conflicts. The South African authorities worried that the violence could spread to Boer farms. These farms were worked by women and children. The farms were evacuated, and people moved to Piet Retief. Farmers from Piet Retief and Wakkerstroom often took their sheep into Swaziland for winter grazing. In January 1900, this practice was discouraged. By April 1900, it was forbidden.

The British also worried about Swaziland. They thought supplies might be smuggled to the Boers through Eswatini. Queen-regent Labotsibeni tried to stay neutral in the larger war. She was focused on making sure her grandson, Sobhuza II, would become king. Sobhuza II was underage. There were other possible candidates for the throne. One was Prince Masumphe, who had ties to the Boers. By May 1900, the Queen worried the Boers might get involved in the succession. She started talking with the British. She planned to flee to their area if needed.

Her messages reached the government of Natal and then Cape Town. A reply from Johannes Smuts assured her that the British had not forgotten the Swazi. British representatives would return to Eswatini soon. Frederick Roberts, a high-ranking military officer, also agreed to contact the Queen. His representatives were to convince her of three things: first, to stop the Boers from occupying the mountains; second, to formally ask for British protection; and third, to end the killings in Eswatini.

British contact with the Swazi helped them in their siege of Komatipoort. This was a nearby South African stronghold. In September 1900, the British captured Komatipoort and Barberton. Some Boers fled into Eswatini. The Swazi disarmed them and took their cattle. The end of South African presence in the area raised questions about what to do with Eswatini. Smuts had been trying to convince the British to take control of Eswatini. By September, he had some support from civil authorities. But military leaders did not want to send forces to occupy the area.

The fall of Komatipoort made Eswatini more important for the Boers. To communicate with their contacts in Mozambique, the Boers had to send messengers through Eswatini. This was hard because British forces could pass through some Swazi areas. By November 1900, the Queen told Roberts and Smuts that she was "doing her best to drive Boers out of her country."

On November 29, 1900, Roberts was replaced by Herbert Kitchener. By late December, Smuts contacted Kitchener's office about Eswatini. Smuts had become the Resident Commissioner of Swaziland. However, the British had no real power over the area. He tried to convince Kitchener to send military forces and put Smuts in charge. Kitchener had a different idea. He started talking directly with Labotsibeni. Kitchener insisted on three points: first, the Swazi must not join the war; second, no British forces would enter Eswatini unless the Boers invaded; and third, the Swazis were now directly under the British Crown. They owed loyalty to Queen Victoria.

In late 1900 and early 1901, there were reports of retreating Boers trying to flee through Eswatini. British forces were sent to make the Boers surrender or flee. On February 9, 1901, a British column captured several Boer wagons and many cattle and sheep near the Swaziland border. Most captured Boers were sent to a camp. On February 11, another column was at the southern border of Eswatini. On February 14, British forces reached Amsterdam. Envoys from the Queen-regent asked for help to drive the Boers from her land. In response, the Imperial Light Horse and the Suffolk Regiment entered Eswatini.

Joined by armed Swazis, the two regiments captured about 30 Boers. Heavy rains slowed their movement. On February 28, 1901, 200 more British soldiers entered Eswatini. This force captured the transport convoy of the Piet Retief Commandos. About 65 Boers were captured. The remaining Commandos retreated to the southern border of Eswatini. They were then captured by British forces there. By early March, the Swazis were taking goods from Boer homes. By this time, another British force had reached Mahamba. Queen-regent Labotsibeni was ordering her Impis (warriors) to clear her land of Boers.

Records from the Devonshire Regiment show that the Swazis were acting as "a ninth column, commanded by the Queen of the Swazis." On March 8, 1901, some remaining Piet Retief Commandos, with women and children, were attacked. This attack was supposedly led by Chief Ntshingila Simelano. Thirteen Boers and one African guide were killed. The incident scared other Boers. Between March 8 and 11, about 70 Boers and various women and children surrendered to the British. They preferred this to facing the Swazis. The British warned Labotsibeni to stop further killings.

On April 11, 1901, Louis Botha complained to Kitchener. He said British officers were making the Swazis fight the Boers. He claimed this led to killings of Boers, women, and children. The British officer, Allenby, said the killings were partly because the Swazi wanted to stop Boer invasions. They also feared what the Boers would do when the British left. Allenby did not allow many armed Swazis to join his column. But he used a few as guides. Smuts finally entered Eswatini that month. But he could not control any British forces.

The presence of British troops allowed the Queen-regent to complain about a unit called "Steinaecker's Horse." This unit was known for taking Boer property. As the Boers became poor, the unit started taking cattle from the Swazi. Labotsibeni complained that this unit was made of robbers. Botha responded by sending a Commando unit against the Horse. They were ordered not to bother the Swazi. The Swazi National Council let them pass. Between July 21 and 23, 1901, the Ermelo Commandos forced most of "Steinaecker's Horse" to retreat. They captured about 35 men and burned Bremersdorp.

Both the British and the Boers continued to be in Eswatini. Small fights happened occasionally. For example, on November 8, 1901, the 13th Hussars captured 14 Boers near Mahamba. These fights ended in February 1902. This was when the last Boer unit in Eswatini was defeated.

In 1903, after the British won the Anglo-Boer War, Eswatini became a British protectorate. Much of its early government was run from South Africa. This lasted until 1906. Eswatini became independent on September 6, 1968. It was then called the Kingdom of Swaziland. Sobhuza II was the king at independence. He had become King in 1899 after his father Ngwane V died. His official crowning was in December 1921. After this, he tried to get land issues resolved in London, but it was not successful.

Swaziland as a British Protectorate (1903–1968)

Quick facts for kids

Swaziland Protectorate

Eswatini/KaNgwane

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903–1968 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: God Save the Queen

|

|||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Mbabane | ||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) Siswati, IsiZulu |

||||||||

| Religion | Congregationalism (Christian mission churches of the London Missionary Society/LMS); Anglicanism, Methodism, Catholicism, Swazi Religion | ||||||||

| Government | Protectorate | ||||||||

| Resident Commissioner | |||||||||

|

• 1903-1907

|

Francis Enraght-Moony | ||||||||

|

• 1964-1968

|

Francis Alfred Lloyd | ||||||||

| Paramount Chief | |||||||||

|

• 1903-1968

|

Sobhuza II | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council (1964–1967) | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||

| 31 March 1903 | |||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1968 | ||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

During the time Eswatini was a British protectorate (1903 to 1968), it was mostly governed by a Resident Commissioner. This person followed rules set by the British High Commissioner to South Africa. These rules were made with the Resident Commissioners. They also took advice from White settlers and the Swazi king. In 1907, Swazi land was divided. One-third was for the Swazi nation (reserves). The other two-thirds became crown and commercial land for Europeans. This division happened in 1909. Swazis living in European areas were given five years to leave.

British Resident Commissioners in Swaziland

| Date | Name |

|---|---|

| 1903–1907 | Francis Enraght-Moony |

| 1907–1916 | Robert Thorne Coryndon |

| Jan 1917 – Oct 1928 | Sir De Symons Montagu George Honey |

| Oct 1928 – 1 Apr 1935 | Thomas Ainsworth Dickson |

| Oct 1935 – Nov 1937 | Allan Graham Marwick |

| Nov 1937 – 30 Sep 1942 | Charles Lamb Bruton |

| 30 Sep 1942 – 25 Aug 1946 | Eric Kellett Featherstone |

| 25 Aug 1946 – 1951 | Edward Betham Beetham |

| 1951–1956 | David Loftus Morgan |

| 1956–1964 | Brian Allan Marwick |

| 1964–1968 | Francis Alfred Lloyd |

In 1921, the British created Swaziland's first law-making group. It was called the European Advisory Council (EAC). It had elected White representatives. Their job was to advise the British Resident Commissioner on matters not related to Swazis. In 1944, the Commissioner changed the EAC's role. He also made the paramount chief (the Swazi king) the official native authority. This meant the king could issue legal orders to the Swazis. But these orders were subject to British restrictions.

Due to the royal family's resistance, this rule was changed in 1952. It gave the Swazi paramount chief more freedom than other British-ruled areas in Africa. Also in 1921, after more than twenty years of Queen Regent Labotsibeni's rule, Sobhuza II became Ingwenyama (lion), or head of the Swazi nation.

In the early years of British rule, it was thought that Eswatini would join South Africa. But after World War II, South Africa increased its racial discrimination. This made the United Kingdom prepare Eswatini for full independence. Political activity grew in the early 1960s. Several political parties were formed. They competed for power and economic growth. However, these parties were mostly in cities. They had few connections to rural areas, where most Swazis lived.

The traditional Swazi leaders, including King Sobhuza II, formed the Imbokodvo National Movement (INM). This group was popular because it was closely linked to the Swazi way of life. The protectorate government decided to hold an election in mid-1964. This would be for the first legislative council where Swazis could participate. The INM and four other parties competed. The INM won all 24 elected seats.

Swazi soldiers also served in World War II.

Gaining Independence (1968–1980s)

Before independence, the INM had become very strong politically. The INM then adopted many demands from other parties. This included the demand for immediate independence. In 1966, the UK Government agreed to discuss a new constitution. A committee agreed on a constitutional monarchy for Swaziland. This meant a king would rule with a parliament. Self-government would follow parliamentary elections in 1967. Swaziland became independent on September 6, 1968.

Swaziland's first elections after independence were in May 1972. The INM received almost 75% of the votes. The Ngwane National Liberatory Congress (NNLC) received just over 20% of the votes. This gave the NNLC three seats in parliament.

Because of the NNLC's success, King Sobhuza canceled the 1968 constitution on April 12, 1973. He also dissolved parliament. He took all government powers himself. He banned all political activities and trade unions. He said his actions removed foreign political practices that did not fit the Swazi way of life. In January 1979, a new parliament was formed. Its members were chosen partly by indirect elections and partly by the king.

King Sobhuza II died in August 1982. Queen Regent Dzeliwe then became the head of state. In 1984, a disagreement led to a new prime minister. It also led to Dzeliwe being replaced by a new Queen Regent, Ntombi. Ntombi's only child, Prince Makhosetive, was named heir to the Swazi throne. At this time, real power was with the Liqoqo. This was a traditional advisory group. They claimed to give binding advice to the Queen Regent. In October 1985, Queen Regent Ntombi showed her power by dismissing the main leaders of the Liqoqo.

Prince Makhosetive returned from school in England. He became King Mswati III on April 25, 1986. This helped end the ongoing internal disagreements. Soon after, he ended the Liqoqo. In November 1987, a new parliament was elected, and a new cabinet was appointed.

Recent History (1980s and 1990s)

Mswati III is the current king of Eswatini. He has ruled since his crowning in 1986. He rules with Queen Mother Ntombi Tfwala. In 1986, Sotsha Dlamini became Prime Minister. In 1987, the king dissolved parliament early. Eswatini then held its third parliamentary election under the traditional tinkhundla system.

In 1988 and 1989, an underground political party, PUDEMO, criticized the king and his government. They called for 'democratic reforms'. To address this political challenge and growing calls for more government accountability, the king and prime minister started a national discussion. This discussion was about Eswatini's future government. This led to some political changes approved by the king. These included direct and indirect voting in the 1993 national elections. In this election, voters were registered, and the number of voting areas increased. The election was considered fair.

Eswatini's economy and population grew in the 1980s. The economy grew by about 3.3% each year between 1985 and 1993. The population grew by about 3% each year during the same time. Eswatini's economy in the 1980s still relied on South Africa. About 90% of imports came from South Africa. About 37% of exports went to South Africa. Eswatini, along with Lesotho, Botswana, and South Africa, were members of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Government income depended heavily on money from this Union. This money made up between 48.3% and 67.1% of state revenues between 1981 and 1987.

The 1990s saw more student and worker protests. They pushed the king to make reforms. Progress toward constitutional reforms began. This led to the current Eswatini constitution in 2005. This happened despite objections from political activists. The current constitution does not clearly state the status of political parties. The first election under the new constitution was in 2008. Members of parliament were elected from 55 areas (tinkhundla). These MPs served five-year terms until 2013.

In 2011, Eswatini faced an economic crisis. This was due to less money from SACU. The government of Eswatini asked for a loan from South Africa. However, the Swazi government did not agree with the loan's conditions, which included political reforms. During this time, there was more pressure on the Swazi government for reforms. Public protests by groups and unions became more common. Improvements in SACU money from 2012 eased the financial pressure on the Swazi government. The new parliament was elected on September 20, 2013. Sibusiso Dlamini was reappointed prime minister for the third time by the king.

In 1989, Sotja Dlamini was removed as prime minister. Obed Dlamini, a former trade union leader, replaced him. He was prime minister until 1993. Then Prince Mbilini took over. During both Obed's and Mbilini's time, there was growing labor unrest. This led to a big general strike in 1997. After this strike, Prince Mbilini was replaced by Sibusiso Dlamini as Prime Minister.

The constitution for independent Swaziland was created by Britain in November 1963. It set up legislative and executive councils. The Swazi National Council (Liqoqo) opposed this. Despite this, elections happened. The first Legislative Council of Swaziland was formed on September 9, 1964. Changes to the original constitution were accepted by Britain. A new constitution was created, setting up a House of Assembly and Senate. Elections under this constitution were held in 1967.

After the 1973 elections, King Sobhuza II suspended the constitution. He then ruled the country by decree until his death in 1982. At this point, Sobhuza II had ruled Eswatini for 83 years. This made him the longest-ruling monarch in history. After his death, Queen Regent Dzeliwe Shongwe was head of state. In 1984, she was replaced by Queen Mother Ntombi Twala. Mswati III, Ntombi's son, was crowned king on April 25, 1986.

On April 19, 2018, King Mswati III announced that the Kingdom of Swaziland had renamed itself the Kingdom of Eswatini. This was to mark the 50th anniversary of Swazi independence. The new name, Eswatini, means "land of the Swazis" in the Swazi language. It was also partly to avoid confusion with Switzerland.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Suazilandia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Suazilandia para niños