History of Lesotho facts for kids

The history of people living in the area now known as Lesotho goes back thousands of years. Lesotho, then called Basotholand, became a single country under King Moshoeshoe I in 1822. Under King Moshoeshoe I, the Basotho people joined other groups. They fought against a time of great trouble and movement called the Lifaqane, which was linked to famine and the rule of Shaka Zulu from 1818 to 1828.

The country's growth was shaped by contact with British and Dutch settlers from the Cape Colony. Missionaries invited by Moshoeshoe I created a writing system for the Sesotho language between 1837 and 1855. Lesotho set up ways to talk with other countries and got guns. These guns were used against the Europeans and the Korana people who were moving into their lands.

There were often fights over land with both British and Boer settlers. Moshoeshoe had a big win against the Boers in the Free State–Basotho War. But after a final war in 1867, he asked Queen Victoria for help. She agreed to make Basutoland a British protectorate. In 1869, the British signed a treaty with the Boers. This treaty set the borders of Basotholand, which later became Lesotho. It gave away western lands, making Moshoeshoe's kingdom half its original size.

The British control over Basotholand changed over time. Lesotho finally became independent in 1966 and was called the Kingdom of Lesotho. However, the ruling Basotho National Party (BNP) lost the first elections after independence. The Basotho Congress Party (BCP) won, but Leabua Jonathan of the BNP refused to give up power. He declared himself Prime Minister. The BCP started a rebellion, which led to a military takeover in January 1986. This forced the BNP out of office.

Power then went to King Moshoeshoe II, who had been a ceremonial king. But he was forced to leave the country when the military no longer supported him. His son was then made King Letsie III. The country remained unstable. In August 1994, King Letsie III took control by force. Things became more stable in 1998 when the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) won elections. These elections were seen as fair by international observers. Despite protests from other parties, the country has been fairly stable since then.

Contents

Ancient History of Lesotho

Lesotho's southern and eastern mountains, including the Maloti Mountains, were home to the San people for thousands of years. We know this from their rock art. The San people lived by hunting animals and gathering plants, moving from place to place.

Later, during a big movement of people called the Bantu expansion, Bantu-speaking groups settled in the lands that are now Lesotho. They also settled in the fertile areas around modern-day Lesotho. The AmaZizi people were among the first to settle in Lesotho after this expansion. The Zizi were known as skilled iron workers. Both the Zizi and nearby tribes said they came from the early Bantu settlers. These settlers later split into the Nguni and the Sotho groups.

Medieval History of Lesotho

The Lesotho highlands attracted people who hunted and gathered between 550 and 1300 AD. This was during a time called the Medieval Warm Period. During this time, the Drakensberg area was completely empty. Some people living in the highlands at that time also kept cattle for food.

Early Modern History of Lesotho

The Basotho people faced several big problems in the early 1800s. One idea is that the first problems came from Zulu groups. These groups were forced to move from their homes as part of the Lifaqane (or Mfecane). They caused a lot of damage to the Basotho people they met as they moved.

Another problem was that soon after the Zulu groups passed, the first Voortrekkers arrived. These were Dutch settlers who traveled north. Some of them were welcomed by the Basotho during their difficult journey. Early Voortrekker stories describe how the lands around the Basotho's mountain home had been burned and destroyed. This left empty land that later Voortrekkers began to settle.

However, this way of looking at history for southern Africa is debated. Some historians argue that the Mfecane did not happen as described. They say the Zulu were not more aggressive than other groups. They also argue that the land the Voortrekkers saw as empty was not settled because people did not value open plains for grazing animals.

Basutoland Under British Rule

Wars with the Boers

In 1818, Moshoeshoe I brought different Basotho groups together and became their king. During his rule (1823–1870), there were many wars (1856–68) with the Boer settlers. These settlers had moved into traditional Basotho lands. These wars led to a large loss of land, now known as the "Lost Territory."

A treaty was signed with the Boers of Griqualand in 1843. An agreement was also made with the British in 1853 after a small war. However, arguments with the Boers over land started again in 1858 with Senekal's War. They became more serious in 1865 with the Seqiti War. The Boers won several battles, killing about 1,500 Basotho soldiers. They took a large area of arable land (land good for farming). They kept this land after a treaty was signed at Thaba Bosiu.

More fighting led to an unsuccessful attack on Thaba Bosiu by the Boers. A Boer commander, Louw Wepener, was killed. But by 1867, much of Moshoeshoe's land and most of his forts had been taken.

Fearing defeat, Moshoeshoe asked High Commissioner Philip Wodehouse for British help again. On March 12, 1868, the British government agreed to protect the territory. The Boers were told to leave. In February 1869, the British and Boers agreed to the Convention of Aliwal North. This agreement set the borders of the protectorate. The farming land west of the Caledon River stayed with the Boers. This area is called the Lost or Conquered Territory. Moshoeshoe died in 1870 and was buried on top of Thaba Bosiu.

Becoming Part of the Cape Colony

In 1871, the British protectorate was added to the Cape Colony. The Basotho people resisted the British. In 1879, a southern chief named Moorosi started a rebellion. His fight was stopped, and he was killed. The Basotho then began to fight among themselves over how to divide Moorosi's lands.

The British tried to take away weapons from the local people. Much of the colony rebelled in the Gun War (1880-1881). They caused many losses for the British forces sent to stop them. A peace treaty in 1881 did not completely stop the fighting.

Returning to British Control

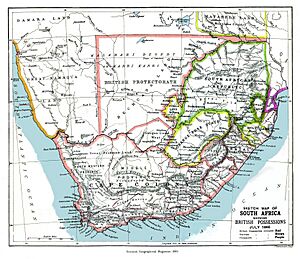

The Cape Town government could not control the territory. So, in 1884, it was returned to direct British control as the Territory of Basutoland. The colony was bordered by the Orange River Colony, Natal Colony, and Cape Colony. It was divided into seven administrative districts. These were Berea, Leribe, Maseru, Mohale's Hoek, Mafeteng, Qacha's Nek and Quthing.

The colony was ruled by the British Resident Commissioner. He worked with the pits (national assembly) of traditional chiefs, who were led by one main chief. Each chief ruled a part of the territory. The first main chief was Lerothodi, Moshoeshoe's son. During the Second Boer War, the colony remained neutral. The population grew from about 125,000 in 1875 to 349,000 by 1904.

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, Basutoland was still controlled by the British. There were talks about transferring it to the Union. However, the people of Basutoland did not want this, so it did not happen.

During World War I, over 4,500 Basotho joined the military. Most served in the South African Native Labour Corps, which worked on the Western Front. In 1916, Basutoland raised over £40,000 to help with the war. A year later, the ship SS Mendi sank, and over 100 Basotho were killed.

The Basotho people in Basotholand had a different future than those in the lands that became the Orange Free State. The Orange Free State became a Boer-ruled area. After the Boer War, the British took control. This colony was later added to the Union of South Africa as one of its provinces. It is still part of modern-day Republic of South Africa, now called the Free State.

In contrast, Basotholand, along with Bechuanaland and Swaziland, was not included in the Union of South Africa. These protectorates became independent countries in the 1960s. By being a protectorate, Basotholand and its people were not under Afrikaner rule. This saved them from experiencing Apartheid, a system of unfair rules. They generally did better under British rule. Basotho people in Basotholand had better health services and education. They also gained more political freedom through independence. However, these protected lands had less ability to make money than the "lost territory" given to the Boers.

After Britain joined World War II, it was decided to recruit people from the High Commission Territories (HTC) of Swaziland, Basutoland, and Bechuanaland. Black citizens from these areas were recruited into the African Auxiliary Pioneer Corps (AAPC). This was a labor unit because some people did not want black soldiers to carry weapons. Recruiting for the AAPC started in July 1941. By October, 18,000 people had arrived in the Middle East. A group called the Commoner's League in Basutoland was banned. Its leaders were put in prison because they asked for better training for the recruits.

The AAPC did many kinds of manual labor. They helped the Allied war effort during campaigns in North Africa, Dodecanese, and Italy. During the Italian campaign, some AAPC units even helped British artillery units.

On May 1, 1943, the British troopship SS Erinpura was sunk. This caused the loss of 694 men from AAPC's Basotho Companies. It was the unit's worst loss of life during the war. A total of 21,000 Basotho joined the war effort. 1,105 of them died. Basotho women also helped by knitting warm clothes for the soldiers.

From 1948, the South African National Party started its apartheid policies. This indirectly ended any support among Basotho people or British colonial authorities for Lesotho to join South Africa.

In 1955, the Basutoland Council asked to make its own laws. In 1959, a new constitution gave Basutoland its first elected legislature. This was followed by general elections in April 1965. In these elections, the Basotho National Party (BNP) won 31 seats, and the Basutoland Congress Party (BCP) won 25 of the 65 seats.

Kingdom of Lesotho

On October 4, 1966, the Kingdom of Lesotho became fully independent. It was governed by a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral Parliament. This Parliament had a Senate and an elected National Assembly.

Early results of the first elections after independence in January 1970 showed that the Basotho National Party (BNP) might lose power. Prime Minister Chief Leabua Jonathan, who led the BNP, refused to give up power to the rival Basotholand Congress Party (BCP). Many believed the BCP had won the elections. Prime Minister Leabua Jonathan said there were problems with the election. He cancelled the election results, declared a national emergency, stopped the constitution, and closed the Parliament.

In 1973, a temporary National Assembly was created. It had many members who supported the government and was mostly controlled by the BNP, led by Prime Minister Jonathan. Besides the Jonathan government making Basotho leaders and the local people unhappy, South Africa had almost closed Lesotho's borders. This was because Lesotho supported the African National Congress (ANC), a political group fighting for rights. South Africa also publicly threatened to take stronger action against Lesotho if the Jonathan government did not stop the ANC presence. This opposition from inside and outside the country led to violence and disorder in Lesotho. This eventually resulted in a military takeover in 1986.

Under a military order in January 1986, the King was given executive and law-making powers. He was to act on the advice of the Military Council, a group of leaders from the Royal Lesotho Defense Force (RLDF) who took power. A military government led by Justin Lekhanya ruled Lesotho. They worked with King Moshoeshoe II and a civilian cabinet chosen by the King.

In February 1990, King Moshoeshoe II lost his executive and law-making powers. He was sent away by Lekhanya, and many ministers were removed. Lekhanya accused them of causing problems in the army and harming Lesotho's image abroad.

Lesotho's Path to Democracy

Lekhanya announced the creation of a National Constituent Assembly. Its job was to write a new constitution for Lesotho to return to democratic, civilian rule by June 1992. However, before this could happen, Lekhanya was removed from power in 1991 by a rebellion of younger army officers. This left Phisoane Ramaema as the head of the Military Council.

King Moshoeshoe II at first refused to return to Lesotho under the new rules. These rules meant the King would only have ceremonial powers. So, Moshoeshoe's son was made King Letsie III. In 1992, Moshoeshoe II returned to Lesotho as a regular citizen. Then in 1995, King Letsie gave up the throne for his father. After Moshoeshoe II died in a car accident in 1996, King Letsie III became king again.

In 1993, a new constitution was put in place. It stated that the King had no executive power and could not get involved in politics. Then, multi-party elections were held. The BCP won by a lot, taking every seat in the 65-member National Assembly. Prime Minister Ntsu Mokhehle led the new BCP government.

In early 1994, the country became more unstable. First the army, then the police and prison services, had rebellions. In August 1994, King Letsie III, with some military members, took control by force. He stopped Parliament and appointed a ruling council. But because of pressure from inside and outside the country, the elected government was put back in place within a month.

In 1995, there were a few incidents of unrest. This included a police strike in May for higher wages. But mostly, there were no serious challenges to Lesotho's government in 1995-96. In January 1997, armed soldiers stopped a violent police rebellion and arrested those involved.

In 1997, disagreements within the BCP leadership caused a split. Dr. Mokhehle left the BCP and formed the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD). Two-thirds of the parliament members followed him. This allowed Mokhehle to stay as prime minister and leader of a new ruling party. The BCP became an opposition party. The remaining BCP members did not accept this and stopped attending Parliament sessions. Multi-party elections were held again in May 1998.

Although Mokhehle finished his term as prime minister, he did not run for a second term due to his poor health. The LCD won the elections by a lot, getting 79 of the 80 seats in the expanded Parliament. As a result, Mokhehle's Deputy Prime Minister, Pakalitha Mosisili, became the new prime minister.

The big election win caused opposition parties to claim there were many problems with how the votes were counted. They said the results were dishonest. However, a commission called the Langa Commission, appointed by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), investigated. Its findings agreed with international observers and local courts that the election results were not affected by these incidents. While the report found the election results were fair, opposition protests in the country grew stronger.

The protests led to a violent demonstration outside the royal palace in early August 1998. There was a lot of violence, looting, injuries, and destruction of property. In early September, younger members of the armed services rebelled. The Government of Lesotho asked a SADC task force to step in. They wanted to prevent a military takeover and bring stability back. So, a joint force of South African and later Botswana troops entered Lesotho on September 22, 1998. They stopped the rebellion and put the democratically elected government back in power. The soldiers who rebelled were put on trial by the military.

After stability returned to Lesotho, the SADC task force left the country in May 1999. Only a small task force, joined by Zimbabwe troops, stayed to train the LDF. Meanwhile, a temporary group called the Interim Political Authority (IPA) was created in December 1998. Its job was to review the voting system. It created a new voting system that made sure smaller parties would have a chance in the National Assembly. The new system kept the existing 80 elected Assembly seats but added 40 seats to be filled based on how many votes parties got.

Elections were held under this new system in May 2002. The LCD won again, getting 54% of the votes. However, for the first time, opposition political parties won many seats. Despite some problems and threats of violence, Lesotho had its first peaceful election. Nine opposition parties now hold all 40 of the proportional seats, with the BNP having the most (21). The LCD has 79 of the 80 constituency-based seats.

In June 2014, Prime Minister Thomas Thabane stopped Parliament because of conflict within his group of parties. This led to criticism that he was weakening the government. In August, after Thabane tried to remove Lieutenant General Kennedy Tlai Kamoli from leading the army, the Prime Minister left the country for three days. He said a military takeover was happening. Kamoli denied that any takeover had occurred.

On May 19, 2020, Thomas Thabane officially stepped down as prime minister of Lesotho. This happened after months of pressure. Moeketsi Majoro, an economist and former Minister of Development Planning, was chosen as Thabane's replacement.

On October 28, 2022, Sam Matekane became Lesotho's new prime minister. He formed a new government with other parties. His Revolution for Prosperity party, formed earlier that year, won the October 7 elections.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Lesoto para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Lesoto para niños

- History of Africa

- History of South Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- History of Eswatini

- List of heads of government of Lesotho

- List of Kings of Lesotho

- Politics of Lesotho

Sources