History of Trinity College, Oxford facts for kids

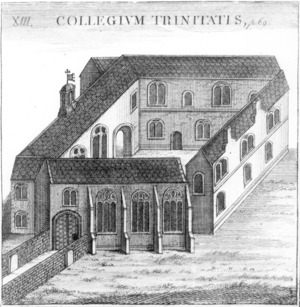

Trinity College, Oxford, has a long and interesting history, stretching back over 450 years! It's one of the oldest colleges at the University of Oxford, founded on March 8, 1555. Trinity College was built on the site of an even older college called Durham College. When it first opened its doors on May 30, 1555, its founder, Sir Thomas Pope, wanted it to be a Catholic college focused on teaching theology (the study of religion). Today, Trinity is a modern college, and it has welcomed both male and female students since 1979.

Contents

How Trinity College Began

In 1553, King Edward VI gave the land and buildings of the old Durham College to two men, Dr. George Owen and William Martyn. Two years later, in February 1555, they sold the property to Sir Thomas Pope. Sir Thomas was a very successful politician who had helped set up another college, Magdalene College, Cambridge. The land he bought in Oxford was perfect, with a library, dining hall, and student rooms already built.

At this time, Queen Mary I was very interested in making Oxford a strong center for Catholic studies again. Sir Thomas Pope, who was wealthy but had no children, likely saw this as a chance to gain influence with the Queen and make sure his family name would be remembered. Just sixteen days after buying the land, on March 8, 1555, he received official permission from the King to start a new college.

The new college was named "The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the Foundation of Thomas Pope." This long name is still used today! The old Durham College had been dedicated to the Virgin Mary, St. Cuthbert, and the Trinity, so it's thought that Trinity College got its name from the last part of that dedication.

Trinity was quite small at first, with a President, twelve fellows (teachers and researchers), eight scholars, and twenty commoners (students). Sir Thomas Pope insisted that the fellows should study theology. He chose Thomas Slythurst to be Trinity's first President. On March 28, 1555, Sir Thomas Pope visited the college and officially transferred all the property to it. Students at Trinity studied classical texts, philosophy (including math and astronomy), and other subjects. The college officially opened its doors to students on May 30, 1555.

Early Years of Trinity (1555–1600)

Trinity College faced some money problems in its early days, especially after Sir Thomas Pope decided to add four more student places. To help, Pope loaned money to the college and slowly gave it more land. By 1557, Trinity owned five large estates, which brought in about £200 in rent, plus more from smaller land holdings. He also sent many valuable items for the chapel, sixty-three books for the library, and kitchen tools. The college rules were also updated and finalized in 1558.

Sir Thomas Pope died on January 29, 1559. His will mentioned Trinity, providing money for a fence between Trinity and its neighbor, St. John's, and for a safe house outside the city for times of plague. His body was later moved to the college chapel.

After Pope's death, Trinity's Catholic focus caused problems with the new Protestant Queen Elizabeth, who became queen in 1558. She quickly removed the Catholic President, Thomas Slythurst. Luckily, the new President, Arthur Yeldard, was practical enough to keep his job for forty years. Trinity slowly changed with the times. The college even melted down its church treasures and bought new English-language psalm books when told to by the Crown. Many fellows who disagreed with these changes left the college. In 1583, Trinity had its first disagreement with Balliol, another college, when Balliol accused Trinity of not being truly Protestant.

The number of commoners (students who weren't religious scholars) grew steadily in the late 1500s. Students were divided into groups: servitors (who worked for their education), battelers, and fellow commoners (from wealthier families). Trinity also hired its first professional gardener during this time.

Trinity in the 1600s

The 1600s at Trinity were shaped by two important Presidents: Ralph Kettell (1599–1643) and Ralph Bathurst (1664–1704).

President Ralph Kettell

Ralph Kettell oversaw many changes. He rebuilt the dining hall and nearby buildings after the hall collapsed in 1618. The library was improved and its collection grew with gifts of books. A librarian was even hired to look after the books. Kettell was good at managing money and raised funds from former students. He also used his own money to improve the college.

Wealthy students had to contribute to a "plate fund," which helped build a large collection of gold and silver items. Trinity became financially stronger, and extra money was used to improve student housing. Kettell also built Kettell Hall nearby to provide more rooms for Trinity students. As a result, the number of students grew to over 100 by 1630.

The English Civil War (1640s)

The 1640s were tough for Trinity because of the English Civil War. In 1642, the college loaned £200 to King Charles I, which was never paid back. In 1643, almost all of Trinity's valuable gold and silver items, worth £537, were taken by the Crown and never seen again. Only a few pieces survived.

Many students and fellows left, and the college had to rent out rooms to members of the King's court. Trinity faced serious financial problems. When Oxford surrendered to Parliament's forces in 1646, representatives from both sides were Trinity graduates. After the war, many royalist supporters in Oxford were removed, including Trinity's President, Hannibal Potter, who had replaced Kettell. Potter was forced to leave and stayed away for 12 years.

After the war, a review showed Trinity had only three fellows, nine scholars, and twenty-six commoners. Some were expelled for not supporting Parliament. A new President, Robert Harris, was put in charge. Trinity slowly recovered and its finances improved. Harris died in 1658, and the fellows quickly elected William Hawes as his successor. Hawes also became ill and resigned shortly before his death, allowing the fellows to elect Seth Ward, a very capable leader. However, Ward didn't stay long.

The Restoration and Ralph Bathurst

The Restoration in the 1660s brought back many people who had been removed, including former President Hannibal Potter. He returned and died in 1664. The new President was Ralph Bathurst, who had been involved with the college for many years. His main goal was to increase the number of students.

Bathurst's Trinity (1664–1704)

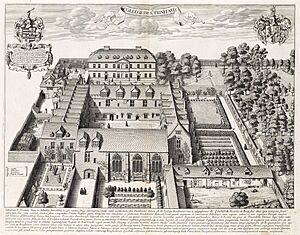

President Bathurst spent about thirty years improving Trinity's buildings. He rebuilt the old chapel, which was falling apart, and replaced the old kitchen. The President's own living quarters were also updated. The new chapel, finished in 1694, was so impressive that it was the only college building visited by Peter the Great during his trip to Oxford.

Bathurst also oversaw the building of a new block of rooms, designed by the famous architect Sir Christopher Wren. This building now forms the northern side of the college's "Garden Quadrangle." Funds were raised from former students and fellows, and the new block was ready by 1668. Bathurst wanted to expand even more, so an identical building was constructed from 1682–84, forming the western side of the Garden Quadrangle.

As Bathurst hoped, these improvements led to more students joining Trinity, and they were generally wealthier. By the 1680s, there were over a hundred students again. Trinity became known as Oxford's most expensive college, attracting students from England's middle classes. The college still admitted a few servitors (students who worked for their education) each year.

College life also changed. While prayers were still required, the rules for missing them became less strict, as did curfew times. Students from important families might not have been punished as strictly for poor performance. However, the daily schedule still included seven hours of study for all students. Lectures covered more subjects, including "experimental philosophy" in addition to classical education. Trinity also had the first college library specifically for undergraduate students in Oxford.

Trinity in the 1700s

The 1700s were a quieter time for Trinity College. President Bathurst died in 1704 and was followed by several other Presidents. George Huddesford served the longest, for 44 years, starting in 1731. He was later replaced by Joseph Chapman, who remained President until 1805.

More floors were added to the Garden Quadrangle buildings in 1728, changing the look of Wren's original design. The dining hall was also updated around 1774, changing from an older Gothic style to a more decorative Baroque style. Trinity's land grew slightly for the first time since it was founded, with new land purchased between 1780 and 1787.

Two of Britain's Prime Ministers, Lord North and William Pitt the Elder, studied at Trinity during this century. The college library, which got its first rules for borrowing books in 1765, was often visited by the famous writer Samuel Johnson. However, fewer Trinity students actively pursued their degrees during this time. The cost of living increased, and religious rules became less strict, meaning that Trinity's students were mostly from the middle and upper classes, who didn't always need a formal degree. The last servitor was admitted in 1763.

College culture changed, with concerns about student behavior and keeping dogs for hunting. Guns were banned in 1800. To improve academics, the college started holding fixed oral exams twice a year for all students from 1789 onwards.

Trinity in the 1800s

At the start of the 1800s, there was a general concern that Oxford colleges weren't focused enough on academics. This led the University to introduce stricter exams for degrees. Trinity College generally welcomed these educational reforms. Exams became more standardized, and by 1817, a student named John Henry Newman noted that Trinity had become "the strictest of colleges." However, he also observed that it had been ten years since a Trinity student had earned the highest honors. By the time John Wilson became President in 1850, it was clear that both Trinity and the University needed reforms to focus more on learning rather than just religious teaching.

A royal commission (a special committee) was set up in 1850 to look into university practices. President Wilson wanted to improve Trinity, suggesting higher pay for lecturers so they could provide daily tutorials, better library access for students, and a system of exhibitions (scholarships). The royal commission also made it easier for colleges to change their original rules. By 1870, eight fellows no longer had religious duties, and by 1882, it was optional for fellows (except the Chaplain) to be priests. For the first time, marriage was also allowed for Trinity fellows.

Trinity also decided to open its scholarships to all students in 1816. From 1825, former scholars could become fellows, though religious rules still applied to that position. In 1843, Trinity allowed students from other colleges to become fellows at Trinity.

Blakiston's Trinity (1907–1938)

Herbert Blakiston became President of Trinity on March 17, 1907. He had been at Trinity for over 25 years, first as a student, then a tutor, chaplain, and senior tutor. He even wrote the college's first official history in 1898. Blakiston was efficient but sometimes seemed cold. He was careful with money and remained President until 1938. He continued to work for the college until his death in 1942.

During this time, students sometimes had wild parties, setting bonfires. Blakiston didn't usually expel students for this, as he didn't want to discourage other middle-class families from sending their sons to Trinity. For similar reasons, he only admitted one non-white student during his 24 years and strongly opposed allowing female students into the university in 1920. Trinity's rivalry with the more liberal Balliol College was also very strong during this period.

When World War I started in 1914, the number of students at Trinity dropped sharply. In May, there were 150 students, but by the end of the year, there were only about 30, and by the end of the war, it was in single digits. Blakiston wrote to the families of students who died, including the family of Noel Chavasse, a soldier who received the highest military honor twice. With so few paying students, college finances were weak, and many staff, including Blakiston, took pay cuts. Money from rooms rented by the armed forces helped the college in the long term. A new bathhouse was even built by the soldiers staying there, at no cost to the college.

Many fellows also joined the army, forcing Blakiston to take on more administrative duties for both the college and the university, including being the Vice-Chancellor of the university from 1917 to 1920. However, he always remained focused on the college and worked to keep Trinity independent.

In total, 820 people connected to Trinity served in the war, and 153 of them died. After the war, Trinity quickly recovered, with student numbers back to normal within two years. In 1919, Blakiston suggested building a new library as a memorial to those who died, and this idea was chosen. The new library, which opened in 1928, was paid for by many generous donations. Blakiston took a personal interest in its design.

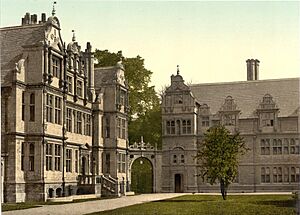

During this period, Trinity was still better known for its sports than its academics, though some fellows, like Cyril Hinshelwood, did important research. Other building work included restoring the chapel and building a new bathhouse.

Recent History (1939–Present)

Trinity College was not as badly affected by World War II (which started in September 1939) as it was by the first war. The university offered special courses for future officers, and Trinity also hosted Balliol students after their own accommodation was taken over. Trinity kept a good number of students and managed to maintain a good standard of living despite wartime shortages. However, the number of casualties was still high; 133 former Trinity students died serving, many in the Royal Air Force.

After the war, the number of students at Trinity increased significantly, though it remains one of Oxford's smaller colleges. New student accommodation, called the Cumberbatch buildings, opened in 1966. The college also benefited from a university-wide effort to clean the many stone buildings in Oxford that had turned black over centuries. The dining hall was renovated just in time for Trinity to host the Queen, Prince Philip, and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in 1960.

As more graduate students joined, a special common room for them, the Middle Common Room, was created in 1964. The number of fellows also increased. These expansions were mostly paid for by donations. Later additions included properties on Rawlinson Road (1970) and Staverton Road (1986), and a new staircase of rooms on site (1992).

As government funding for poorer students grew, Trinity's image as a college mainly for the middle classes seemed old-fashioned. The rivalry with Balliol College became strong again, leading to some well-known events. Slowly, many of the college's stricter traditions began to disappear. This period of change sped up under President Alexander George Ogston. Trinity got its first female lecturer in 1968. Students were allowed to have overnight guests from 1972 and weekend guests from 1974. The late-night curfew was mostly removed in 1977.

By this time, the college also changed from using college servants to having professional staff. This meant that breakfast and lunch became self-service, and the first student kitchen facilities were provided in 1976. The student common room also started managing its own money from 1972.

By far the most important change was the admission of the first women to Trinity in October 1979. This change went smoothly. The first female fellow was elected in 1984, completing the shift from a traditional, male-only institution to a modern, co-educational college.

In 2017, Trinity's first woman President, Hilary Boulding, celebrated sixteen women who had studied at Trinity in a poster and booklet called "Feminae Trinitatis." These included famous people like Dame Frances Ashcroft, Siân Berry, Dame Sally Davies, Olivia Hetreed, Kate Mavor, Sarah Oakley, Roma Tearne, and opera singer Claire Booth.

In 2019, the Cumberbatch Building was taken down to make way for the new Levine Building. This building is expected to be finished by the end of 2021. It will include 46 new student bedrooms, an auditorium, teaching rooms, a function room, and a café. It is named after Peter Levine, who studied at Trinity in the 1970s. His very generous donation, given in memory of his parents, made this project and many other college improvements possible.

The grounds of Trinity College were partly the inspiration for "Fleet College" in Charles Finch's book The Last Enchantments.

|

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |