History of speciation facts for kids

The study of speciation is about how new species form from existing ones. This scientific journey began in the mid-1800s with Charles Darwin. Many scientists back then saw a link between where species lived (biogeography) and how they changed over time (evolution).

In the 1900s, the field of speciation grew a lot. Important scientists like Ernst Mayr studied how species are spread out and related. This area of science became very important during the "modern evolutionary synthesis" in the early 20th century. Since then, research into speciation has grown even more.

Today, the language used to describe speciation is more complex. Scientists still discuss how to group the different ways new species form. They also talk about how species become unable to reproduce with each other (reproductive isolation). The 21st century has seen new ways to study speciation. These include using molecular biology to understand family trees (phylogenetics) and how living things are classified (systematics).

Contents

Early Ideas About New Species

Charles Darwin first wrote about species evolving and splitting into new groups in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species. He called this process specification. The word speciation was first used much later, in 1906, by biologist Orator F. Cook.

Darwin's book mainly focused on small changes within a species. It talked less about how one species might divide into two. Many people think Darwin's book didn't directly explain how new species truly originate. Darwin believed new species formed when they moved into new ecological niches, or specific roles in an environment.

Darwin's Thoughts on Speciation

There is some debate about whether Darwin fully understood how geography affects speciation. In his book, Darwin mentioned how barriers like mountains or oceans can stop animals from moving freely. He said these barriers are important for the differences seen in animals from different parts of the world.

Some historians believe Darwin's ideas on speciation were confusing. They think his views might have led other scientists to misunderstand him. However, Darwin never fully agreed with the idea that geography was the main cause of new species.

Evolutionary biologist James Mallet argues that Darwin's book did discuss speciation. Some of Darwin's friends and later scientists said he failed to explain why different species can't have babies together. But Darwin's notes show he thought about how being separated could lead to new species. Many of Darwin's ideas about speciation are similar to modern theories. These include adaptive radiation, where many new species quickly evolve from one, and ecological speciation.

Darwin's Puzzles

When thinking about how new species begin, Darwin faced two big questions:

- How do new species evolve?

- Why do we see clear, separate species in nature, instead of a mix of everything?

Scientists now widely agree that a key reason for new species is reproductive isolation. This means different groups can no longer have babies together. Darwin also thought about why species are so distinct.

Darwin was puzzled by why living things are grouped into clear species. In his book, he asked, "Why, if species have descended from other species by tiny changes, do we not see countless forms in between?" He wondered why nature wasn't just a big mix instead of having well-defined species. This puzzle is about not seeing many in-between forms in different places.

Another puzzle was not seeing many in-between forms over time. Darwin knew that many transitional forms must have existed. He wondered why we don't find them in huge numbers in the Earth's rocks. The fact that clear species exist in nature, both now and in the past, suggests that something in nature creates and keeps species separate.

You can learn more about how these puzzles might be solved in the article Speciation.

How Geography Shapes Species

Scientists knew that geography played a role in species even before Darwin. Many naturalists understood that being separated could affect how species relate. For example, in 1833, C. L. Gloger wrote about how birds change based on climate. But he didn't realize that being separated by geography showed how new species had formed in the past.

Another scientist, Wollaston, studied island beetles in 1856. He saw that being isolated was key to their differences. However, he didn't connect this pattern to the formation of new species. One naturalist, Christian Leopold von Buch, did recognize these geographic patterns in 1825. He clearly stated that geographic isolation could lead to new species. Some historians believe Von Buch was likely the first to truly suggest geographic speciation.

In 1868, Moritz Wagner was the first to propose the idea of geographic speciation. He used the term Separationstheorie, meaning "separation theory." Edward Bagnall Poulton, another evolutionary biologist, emphasized how geographic isolation helps new species form. He even created the term "sympatric speciation" in 1904.

Wagner and other naturalists like Karl Jordan and David Starr Jordan noticed something important. Closely related species were often found in different geographic areas. This led them to believe that geographic isolation was very important for new species to appear. Karl Jordan is thought to have seen how changes and isolation work together to create new species. David Starr Jordan supported Wagner's idea in 1905, showing lots of evidence from nature. He said geographic isolation was obvious but often ignored by geneticists.

Most scientists who classify living things (taxonomists) accepted the geographic model of speciation.

Ernst Mayr helped define many early terms used to describe speciation. He brought together all the ideas of his time in his 1942 book, Systematics and the Origin of Species, from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist. He also wrote Animal Species and Evolution in 1963. Like Jordan's work, Mayr's books were based on direct observations of nature. They showed how geographic speciation happens.

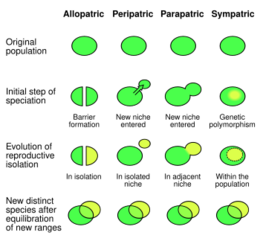

Mayr described three main ways new species form:

- Geographic: Now called allopatric, where populations are completely separated.

- Semi-geographic: Now called parapatric, where populations are next to each other.

- Non-geographic: Now called sympatric, where populations live in the same area.

Mayr's 1942 book was very important for over 20 years and is still useful today.

Mayr focused a lot on how geography helps speciation. Islands were often a key example in his ideas. One of his ideas was peripatric speciation. This is a type of allopatric speciation where a small group breaks off from a main population. This idea came from Wagner's "separation theory." It focused on small, isolated groups of species. This model was later updated to include sexual selection by Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro.

The Modern Understanding of Evolution

Many geneticists in the past didn't connect how genes work with how new species become unable to reproduce with each other. Ronald Fisher suggested a model of speciation in his 1930 book, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. He described how natural selection could act on populations living in the same or nearby areas. He also said that reproductive isolation could be completed by a process called reinforcement.

The main people who brought speciation into the modern understanding of evolution were Ernst Mayr and Theodosius Dobzhansky. Dobzhansky, a geneticist, wrote Genetics and the Origin of Species in 1937. In it, he explained the genetic basis for how speciation could happen. He realized that speciation was a big unsolved problem in biology. He disagreed with Darwin's idea that new species formed by moving into new niches. Instead, he argued that reproductive isolation was due to barriers that stopped genes from flowing between groups.

Later, Mayr did a lot of work on the geography of species. He stressed how important geographic separation and isolation were. His 1942 book filled in the gaps in Dobzhansky's ideas about how so many different living things came to be. Both their works led to our modern understanding of speciation. This also led to a lot of new research. This understanding also spread to plants, with books like Variation and Evolution in Plants by G. Ledyard Stebbins and Plant Speciation by Verne Grant.

In 1947, scientists agreed on a common understanding of evolution. This "20th century synthesis" included speciation. Since then, these ideas have been proven true many times.

Recent Discoveries

After the modern synthesis, speciation research continued, mostly in natural history and biogeography. There was less focus on genetics. The study of speciation has grown the most since the 1980s. This has led to many new publications, terms, ideas, and theories. This "third phase" of work, as Jerry A. Coyne and H. Allen Orr called it, has made the language of speciation more complex. The research has become "enormous, scattered, and increasingly technical."

Since the 1980s, new research tools have made studies stronger. These include new methods, ideas, models, and ways of thinking. Coyne and Orr talk about five main areas of modern research:

- Genetics (the study of genes).

- Molecular biology (studying life at a molecular level) and analysis (like phylogenetics, which looks at evolutionary relationships).

- Comparing different species.

- Mathematical models and computer simulations.

- The role of ecology (how living things interact with their environment).

Scientists who study ecology realized that ecological factors in speciation were not getting enough attention. This led to more research on how ecology helps speciation, which is now called ecological speciation. This focus on ecology created many new terms about barriers to reproduction. For example, allochronic speciation happens when breeding times are different. Habitat isolation occurs when species live in different parts of the same area.

Sympatric speciation, which Mayr once thought was unlikely, is now widely accepted. Research on how natural selection affects speciation, including the process of reinforcement, has also grown.

Scientists have long debated the roles of sexual selection, natural selection, and genetic drift in speciation. Darwin talked a lot about sexual selection. But it wasn't until 1983 that biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard recognized how important sexual selection is for speciation. Natural selection helps speciation when it leads to reproductive isolation. Genetic drift has been studied a lot since the 1950s. This is especially true for models where speciation happens due to random changes in gene frequency.

Mayr supported founder effects. This is when a small group of individuals, like those on an island, break off from a larger population. They have only a small sample of the genes from the main group. Later, other biologists developed similar models of speciation by genetic drift. They noted that islands often have species found nowhere else. The role of selection in speciation is widely supported. However, speciation by founder effect is debated and has faced criticism.

How Speciation is Classified

Throughout the history of speciation research, how to classify and define different ways new species form has been discussed. Julian Huxley divided speciation into three types: geographical, genetic, and ecological. Sewall Wright suggested ten different ways. Ernst Mayr strongly supported the idea that physical, geographic separation of species populations was very important for speciation. He first proposed the three main types we know today: geographic, semi-geographic, and non-geographic. These are now called allopatric, parapatric, and sympatric.

The term "modes of speciation" is not always clearly defined. It often refers to speciation based on a species' geographic distribution. More simply, modern classification often describes speciation as happening along a "gene flow continuum." This means it's based on how genes are exchanged between populations, rather than just geography. Even so, geographic ideas can be translated into gene flow models. But this has sometimes caused confusion in scientific writings.

As research has grown, the geographic way of classifying speciation has been questioned. Some researchers think the traditional classification is old-fashioned. Others still argue for its value. Those who prefer non-geographic classifications often say it simplifies the complex process of speciation.

One main criticism of the geographic framework is that it divides a continuous biological process into separate groups. Another criticism is that if speciation is seen as a continuous flow of genes, then parapatric speciation would cover almost the entire range. Allopatric and sympatric would only be at the extremes.

Coyne and Orr argue that the geographic classification is useful. This is because biogeography controls how strong the evolutionary forces are, as gene flow and geography are clearly linked. Other scientists believe that the sympatric vs. allopatric division is important. It helps to figure out how much natural selection affects speciation.

Some scientists classify speciation by its genetic basis or by what causes reproductive isolation. Here, the geographic ways of speciation are seen as types of assortive mating. Other researchers believe the geographic scheme is a "distraction." They think it might mislead us if the real goal is to understand how natural selection influences differences between species. They say that to fully understand speciation, we must explore the "spatial, ecological, and genetic factors" involved.

History of Speciation Processes

Sympatric Speciation

Sympatric speciation has been a debated topic since Darwin's time. Mayr and other scientists thought Darwin believed new species formed when they entered new ecological niches. This is a form of sympatric speciation. Before Mayr, sympatric speciation was seen as the main way new species formed. In 1963, Mayr strongly criticized this idea, pointing out its flaws. After that, scientists lost interest in sympatric speciation. But it has recently become popular again. Some biologists believe Mayr misunderstood Darwin's view on speciation. Today, sympatric speciation is supported by lab experiments and observations from nature.

Hybrid Speciation

For most of speciation's history, hybridization (when two different species produce offspring) was a debated topic. Botanists (plant scientists) and zoologists (animal scientists) had different views on its role. Carl Linnaeus first suggested hybridization in 1760. Øjvind Winge confirmed a type of hybridization called allopolyploidy in 1917. Later experiments also confirmed these findings. Today, it is widely accepted as a common way new species form.

Historically, zoologists thought hybridization was rare in animals. But botanists found it common in plants. Botanists like G. Ledyard Stebbins and Verne Grant strongly supported the idea of hybrid speciation from the 1950s to the 1980s. Hybrid speciation, also called polyploid speciation, happens when the number of chromosome sets increases. It is like a form of sympatric speciation that happens very quickly. Grant coined the term recombinational speciation in 1981. This is a special type of hybrid speciation where a new species forms from hybridization and cannot reproduce with its parent species. Recently, biologists have increasingly recognized that hybrid speciation can also happen in animals.

Reinforcement

The idea of speciation by reinforcement has a complex history. Its popularity among scientists has changed a lot over time. The theory of reinforcement went through three stages:

- It seemed possible because hybrid offspring were not fit (healthy or able to survive well).

- It seemed unlikely because hybrids might have some fitness.

- It seemed possible again based on studies and realistic models.

Alfred Russel Wallace first proposed it in 1889. He called it the Wallace effect, a term rarely used today. Wallace's idea was different from the modern one. He focused on isolation after mating and group selection. Theodosius Dobzhansky gave the first detailed, modern description of the process in 1937. But the term "reinforcement" itself was not used until 1955 by W. Frank Blair.

In 1930, Ronald Fisher gave the first genetic description of reinforcement in The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. In 1965 and 1970, the first computer simulations were run to test if it was possible. Later studies showed that if hybrids were completely unfit, it led to more isolation before mating.

After Dobzhansky's idea became popular, it gained a lot of support. Dobzhansky suggested it was the final step in speciation. For example, after an allopatric population (separated by geography) comes back into contact. In the 1980s, many evolutionary biologists started to doubt the idea. This was not based on evidence, but on new theories that thought it was an unlikely way for reproductive isolation to happen.

Since the early 1990s, reinforcement has become popular again. Scientists now accept its possibility. This is mainly due to a sudden increase in data, evidence from lab studies and nature, complex computer simulations, and new theoretical work.

The scientific language about reinforcement has also changed. Different researchers use various definitions for the term. It was first used to describe differences in mating calls of Gastrophryne frogs in an area where two groups met. Reinforcement has also been used to describe geographically separated populations that come back into contact.

Some scientists define reinforcement as any increase in isolation before mating. This is as long as it is a response to selection against mating between two different species. Coyne and Orr argue that "true reinforcement" is only when isolation increases between groups that can still exchange genes.

See also

- Laboratory experiments of speciation