G. Ledyard Stebbins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

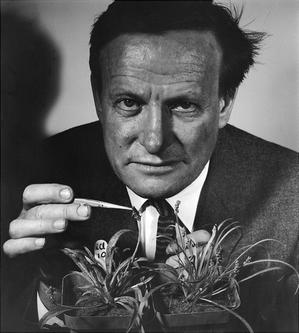

G. Ledyard Stebbins

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

George Ledyard Stebbins Jr.

January 6, 1906 |

| Died | January 19, 2000 (aged 94) |

| Awards |

|

George Ledyard Stebbins Jr. (born January 6, 1906 – died January 19, 2000) was an American scientist. He was a botanist, who studies plants, and a geneticist, who studies how traits are passed down. Many people think he was one of the most important scientists studying evolution in the 1900s.

He earned his Ph.D. (a high-level degree) in botany from Harvard University in 1931. Later, he worked at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he studied how plant species change over time. He worked with E. B. Babcock and other scientists called the Bay Area Biosystematists. This work helped him create a big picture of how plants evolve, using ideas from genetics.

His most famous book was Variation and Evolution in Plants. In this book, he combined genetics with Darwin's idea of natural selection. This helped explain how new plant species form. His book was a key part of the "modern synthesis" of evolution. It still helps scientists understand plant evolution today.

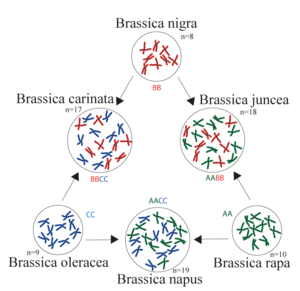

Stebbins also studied how hybridization (when two different species mix) and polyploidy (when plants have extra sets of chromosomes) affect plant evolution. His ideas in this area are still very important for research.

In 1960, Stebbins helped start the Department of Genetics at the University of California, Davis. He was also involved in many groups that supported science and evolution. He became a member of important scientific groups like the National Academy of Sciences. He received the National Medal of Science. Stebbins also helped create science programs for high schools in California. He worked to protect rare plants in the state too.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Stebbins was born in Lawrence, New York. He was the youngest of three children. His father, George Ledyard Stebbins, was a rich real estate investor. He helped develop Seal Harbor, Maine and create Acadia National Park. His mother was Edith Alden Candler Stebbins. Both parents were from New York and were Episcopalian.

Stebbins was known as Ledyard to tell him apart from his father. The family often visited Seal Harbor, where they encouraged their sons to learn about nature. In 1914, his mother got tuberculosis. The family moved to Santa Barbara, California for her health. In California, Stebbins went to the Cate School in Carpinteria. There, he was inspired by Ralph Hoffmann, a teacher who loved natural history, birds, and plants.

Stebbins first studied political science at Harvard University. But by his third year, he decided to focus on botany.

Stebbins started his graduate studies at Harvard in 1928. He first studied how flowering plants are classified and where they grow. He worked with Merritt Lyndon Fernald. Stebbins earned his Master of Arts (MA) degree in 1929. He then continued to work on his Ph.D.

He became interested in using chromosomes to classify plants. His supervisor, Merritt Lyndon Fernald, did not support this method. Stebbins decided to focus his Ph.D. work on the cytology (study of cells) of plant reproduction in the plant group Antennaria. He worked with cytologist E. C. Jeffrey.

During his Ph.D. studies, Stebbins also got advice from geneticist Karl Sax. Sax found some mistakes in Stebbins's work. He disagreed with Stebbins's ideas, which followed Jeffrey's views but not those of other geneticists. Jeffrey and Sax argued about Stebbins's paper. The paper was changed many times to include both their ideas.

Harvard gave Stebbins his Ph.D. in 1931. In March of that year, he married Margaret Chamberlin. They had three children. In 1932, he started teaching biology at Colgate University. While at Colgate, he continued his work on plant genetics. He studied the genetics of Antennaria and how chromosomes behave in hybrid peonies.

Stebbins and Percy Saunders, a biologist, went to the 1932 International Congress of Genetics. There, Stebbins was very interested in talks by Thomas Hunt Morgan and Barbara McClintock. They spoke about chromosomal crossover, which is when chromosomes exchange parts. Stebbins repeated McClintock's experiments with peonies. He published several papers on the genetics of Paeonia. This helped him become known as an important geneticist.

Research at UC Berkeley

In 1935, Stebbins was offered a research job at the University of California, Berkeley. He worked with geneticist E. B. Babcock. Babcock needed help with a big project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. They were studying the genetics and evolution of plants from the group Crepis. They wanted to make Crepis a model organism for genetic studies, like the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Like the plants Stebbins had studied before, Crepis often formed hybrids. It also showed polyploidy (extra sets of chromosomes) and could make seeds without fertilization (called apomixis). Stebbins and Babcock worked together and published many papers and two large books. Their first book in 1937 separated the Asian Crepis species into a new group called Youngia. The second book, published in 1938, was called The American Species of Crepis: their interrelationships and distribution as affected by polyploidy and apomixis.

In this book, Babcock and Stebbins explained the idea of the polyploid complex. This is how polyploidy helps plants evolve. Some plant groups, like Crepis, have many ways of reproducing. They have sexually reproducing plants with normal chromosome numbers. But they also have polyploid plants with extra chromosomes.

Babcock and Stebbins noticed that allopolyploid types, which form from two different species mixing, spread out more widely than other types. They suggested that polyploids formed this way can live in more different environments. This is because they get traits from both parent species. They also showed that hybridization in these polyploid groups could help different species exchange genes. Their work helped us understand how new species form. A Swedish botanist, Åke Gustafsson, called this book the most important work on species formation at that time.

Stebbins wrote a review paper in 1940 called "The significance of polyploidy in plant evolution." It showed that polyploidy was important for creating large, complex, and widespread plant groups. However, he also argued that polyploidy was common only in herbaceous perennials (plants that live for many years and have soft stems). It was less common in woody plants and annuals (plants that live for one year).

He believed that polyploids played a "conservative" role in evolution. This meant they didn't often lead to completely new types of plants. This was because problems with fertility made it hard for them to get new genetic material. He continued this work in a 1947 paper, "Types of polyploids: their classification and significance." In it, he described a system for classifying polyploids. He also shared his ideas about the role of paleopolyploidy (ancient polyploidy) in the evolution of flowering plants. He thought that chromosome number could help build the family tree of plants. These papers were very important and helped other scientists study polyploidy in evolution.

In 1939, Stebbins became a full professor in the Department of Genetics at UC Berkeley. This happened with Babcock's support, after the Department of Botany did not promote him. Stebbins had to teach a course on evolution. While preparing, he became very interested in new research that combined genetics and evolution.

He joined a group called the Bay Area Biosystematists. This group included botanist Jens Clausen, taxonomist David D. Keck, physiologist William Hiesey, and geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky. Stebbins also became friends with botanist Herbert G. Baker. With their encouragement, Stebbins focused his research on evolution. He became involved with the Society for the Study of Evolution in 1946. He was one of the few botanists in this new group.

His research on plant evolution also grew during this time. He studied the genetics of forage grasses, looking at polyploidy and the evolution of Poaceae (the grass family). He published many papers on this topic in the 1940s. He even created an artificial polyploid grass from a normal diploid species, Ehrharta erecta. He used a chemical called colchicine to double its chromosomes. He planted it in the field. After 39 years, he showed that the artificial polyploid was not as successful as its parent plant in a stable environment.

Variation and Evolution in Plants

The Jesup Lectures at Columbia University were important for many key works in the modern evolutionary synthesis. These lectures connected two big ideas: the units of evolution (genes) and natural selection as the main way evolution happens. In 1941, Edgar Anderson and Ernst Mayr gave these lectures. Mayr later published his lectures as Systematics and the Origin of Species.

In 1946, Stebbins was invited to give these important lectures, based on Dobzhansky's recommendation. Stebbins's lectures brought together different fields like genetics, ecology, classification, cell biology, and paleontology. In 1950, these lectures were published as Variation and Evolution in Plants. This book became one of the most important books in 20th-century botany. It brought plant science into the new understanding of evolution. It became a key book in the modern synthesis of evolution.

Variation and Evolution in Plants was the first book to explain broadly how evolution works in plants at the genetic level. It made ideas about plant evolution fit with ideas about animal evolution. It built on Dobzhansky's 1937 book, Genetics and the Origin of Species. Stebbins's book gave a framework for organizing different fields into a new area: plant evolutionary biology.

In the book, Stebbins said that evolution should be studied as a changing process. He said evolution must be looked at on three levels:

- First, the variation among individuals in a group that can interbreed.

- Second, how this variation is distributed and how often it appears.

- Third, how groups become separate and different, leading to new species.

He used the work of scientists like Clausen, Keck, Hiesey, and Turesson. They showed that you could tell the difference between genotypic (genetic makeup) and phenotypic (observable traits) variation. This meant that plants with the same genes could look different in different environments. One of the book's most original parts used the work of C. D. Darlington. It showed that genetic systems like hybridization and polyploidy are also affected by natural selection.

The book didn't offer many new ideas of its own. But Stebbins hoped that by summarizing research on plant evolution, it would "help to open the way towards a deeper understanding of evolutionary problems." The book effectively ended serious belief in other ideas about plant evolution, like Lamarckian evolution, which some botanists still held. After this book, Stebbins was seen as an expert on modern evolutionary theory. He is widely given credit for starting the science of plant evolutionary biology. Variation and Evolution in Plants is still often mentioned in scientific papers today, more than 50 years after it was published.

Stebbins believed his main contribution was applying genetic ideas, already known from other scientists, to botany. He said, "I didn't add any new elements [to the modern synthetic theory] to speak of. I just modified things so that people could understand how things were in the plant world."

UC Davis and Later Life

Stebbins moved to the University of California, Davis in 1950. He was very important in setting up the University's Department of Genetics. He was the department's first chairman from 1958 to 1963. At Davis, his research changed. He started looking at newer areas, like how plants develop and the genetics of crop plants, such as barley. He continued to publish many papers and several books on plant evolution after 1950. He wrote over 200 papers.

In 1954, Stebbins and Edgar Anderson wrote a paper about how important hybridization is for adapting to new environments. They suggested that new adaptations could help plants move into habitats they hadn't used before. They also thought these new adaptations could help create stable hybrid species. After this paper, Stebbins developed the first model of adaptive radiation. This is when many new species quickly evolve from one ancestor.

He suggested that a lot of genetic variation was needed for big evolutionary changes. Because mutations (changes in genes) happen slowly, genetic recombination (when genes mix during reproduction) was the most likely source of this variation. He also thought that variation could be maximized through hybridization. Even today, scientists are still researching whether hybridization is just an accident of evolution or if it's necessary for creating new plant species. Many believe current studies follow the ideas started by Stebbins and Anderson.

Stebbins wrote several books while at UC Davis. These included Flowering Plants: Evolution Above the Species Level, published in 1974. In this book, he discussed how angiosperms (flowering plants) originated, their genetics, and how they develop. He argued that adaptive radiation helped angiosperms become so diverse. He also showed how understanding the genetics and ecology of current species can help us learn about the evolution of ancient species.

He also wrote Processes of Organic Evolution, The Basis of Progressive Evolution, Chromosomal Evolution in Plants, and a textbook called Evolution. For Evolution, he had co-authors Dobzhansky, Francisco Ayala, and James W. Valentine. His last book, Darwin to DNA, Molecules to Humanity, was published in 1982.

Stebbins loved teaching evolution. In the 1960s and 70s, he pushed for teaching Darwinian evolution in public schools. He worked closely with the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. They developed high school lessons based on evolution as the main idea in biology. He also spoke out against groups that promoted scientific creationism.

Stebbins was active in many science organizations. These included the International Union of Biological Sciences and the Botanical Society of America. He was also President of the American Society of Naturalists. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1952. Stebbins received many awards for his work. These included the National Medal of Science and the Gold Medal from the Linnean Society of London. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1952. He received the 1983 Leidy Award.

In his later life, Stebbins was active in protecting nature in California. He started a California Native Plant Society branch in Sacramento in the early 1960s. Through this group, he created field trips to get people interested in California's native plants. He also worked to find and record rare plants. Stebbins was the state President of the Society in 1966. The society helped stop the destruction of a beach on the Monterey Peninsula. He called it "Evolution Hill." This area is now known as the S.F.B. Morse Botanical Area and is protected. He was a major helper for the Society's 1996 book, California's Wild Gardens: A Living Legacy. Stebbins also helped create the Inventory of Rare and Endangered Vascular Plants of California. This list is still used by state and federal groups for conservation. Stebbins was also a member of the Sierra Club.

During his time at UC Davis, he taught over 30 graduate students. They studied genetics, developmental biology, and agricultural science. In 1973, Stebbins gave his last lectures at UC Davis. He became a professor emeritus, meaning he retired but kept his title. After retiring, he traveled a lot, taught, and visited other scientists for 20 years. His last paper, "A brief summary of my ideas on evolution," was published in 1999. In the same year, he and Ernst Mayr received the Distinguished Service award from the American Institute of Biological Sciences.

A meeting was held by the National Academies of Science in 2000. It celebrated the 50th anniversary of his book Variation and Evolution in Plants. Stebbins died at his home in Davis that same year from a cancer-related illness. He was honored at a Unitarian memorial service. He had been active in the church in his later years after marrying his second wife, Barbara Monaghan Stebbins, in 1958. His ashes were scattered at Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve.

Legacy and Honors

Stebbins made a huge contribution to science and botany. He created a way of thinking about plant evolution. This included modern ideas about plant species and how they form. Besides his seven books, he wrote over 280 journal articles and book chapters. A collection of his scientific papers was published in 2004. It was called The Scientific Papers of G. Ledyard Stebbins (1929–2000) (ISBN: 3-906166-15-5).

In 1980, the University of California, Davis, named a piece of land near Lake Berryessa, California, the Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve. This was to honor his work in conservation and evolutionary science. The reserve is part of the University of California Natural Reserve System. The UC Davis Herbarium has a G. Ledyard Stebbins student grant program. It was started to celebrate his 90th birthday.

Several plants are named after Stebbins to honor him. These include Calystegia stebbinsii, Lomatium stebbinsii, Harmonia stebbinsii, Elymus stebbinsii, and Lewisia stebbinsii.

Key Publications

- Variation and Evolution in Plants (1950)

- Processes of Organic Evolution (1966)

- The Basis of Progressive Evolution (1969)

- Chromosomal Evolution in Higher Plants (1971) (ISBN: 0-7131-2287-0)

- Flowering plants: evolution above the species level (1974). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1974. ISBN 978-0-674-30685-1. https://archive.org/details/floweringplantse0000steb.

- Evolution (1977) with Dobzhansky, Ayala and Valentine

- Darwin to DNA, Molecules to Humanity (1982) (ISBN: 0-7167-1331-4)

See also

In Spanish: George Ledyard Stebbins para niños

In Spanish: George Ledyard Stebbins para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |