Barbara McClintock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Barbara McClintock

|

|

|---|---|

McClintock in 1947 within her laboratory

|

|

| Born |

Eleanor McClintock

June 16, 1902 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Died | September 2, 1992 (aged 90) Huntington, New York, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Cornell University (BS, MS, PhD) |

| Known for | Work in genetic structure of maize |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cytogenetics |

| Institutions | University of Missouri California Institute of Technology Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory |

| Thesis | A Cytological and Genetical Study of Triploid Maize (1927) |

| Signature | |

Barbara McClintock (born June 16, 1902 – died September 2, 1992) was an amazing American scientist. She was a cytogeneticist, which means she studied chromosomes and how they work inside cells. In 1983, she won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her groundbreaking discoveries.

McClintock earned her PhD in botany (the study of plants) from Cornell University in 1927. There, she became a leader in studying the genetics of maize (corn). This became her main focus for her whole career. She spent years looking at corn chromosomes and how they changed when corn plants reproduced.

She even invented a way to see corn chromosomes clearly under a microscope! Using this method, she showed many basic ideas about genetics. For example, she proved that chromosomes can swap information, a process called genetic recombination. She also created the first genetic map for corn, showing where certain traits were located on the chromosomes.

McClintock also discovered the important roles of telomeres and centromeres. These are special parts of chromosomes that help keep our genetic information safe. By 1944, she was recognized as one of the best in her field. She received many important awards and became a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

In the 1940s and 1950s, McClintock made her most famous discovery: transposition. This means that genes can "jump" or move around on chromosomes. She showed that these jumping genes control whether certain physical traits, like corn kernel color, are turned on or off. At first, other scientists were doubtful about her ideas. Because of this, she stopped publishing her findings in 1953.

Later in her life, McClintock studied different types of corn from South America. Her research became widely accepted in the 1960s and 1970s. This happened when other scientists found similar "jumping genes" in other living things. Finally, she received many honors, including the Nobel Prize in 1983. She is still the only woman to win an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Contents

Early Life and Discoveries

Growing Up Independent

Barbara McClintock was born Eleanor McClintock on June 16, 1902, in Hartford, Connecticut. She was the third of four children. Her father, Thomas Henry McClintock, was a doctor. Her mother was Sara Handy McClintock.

When she was very young, her parents thought the name "Eleanor" was too "delicate" for her. So, they changed her name to Barbara. Barbara was a very independent child from a young age. She later said this was her "capacity to be alone."

For a few years, she lived with an aunt and uncle in Brooklyn, New York. This helped her parents financially while her father started his medical practice. She was known as a solitary and independent child. She was close to her father but had a difficult relationship with her mother.

In 1908, her family moved to Brooklyn. Barbara finished high school early in 1919 at Erasmus Hall High School. She discovered her love for science during these years. She wanted to go to Cornell University's College of Agriculture. Her mother worried that going to college would make her "unmarriageable." But her father allowed her to go just before classes started in 1919.

Exploring Corn's Secrets at Cornell

Barbara started at Cornell's College of Agriculture in 1919. She joined student government but soon realized she preferred not to be in formal groups. Instead, she enjoyed music, especially jazz. She studied botany and earned her bachelor's degree in 1923.

Her interest in genetics began in 1921 when she took her first course in the subject. Her professor, C. B. Hutchison, was impressed by her interest. He invited her to a special graduate genetics course in 1922. McClintock said this phone call changed her future. She decided to focus on genetics from then on.

During her graduate studies, McClintock helped create a group that studied cytogenetics in corn. This new field combined plant breeding with cell study. The group included other famous scientists like Marcus Rhoades and future Nobel winner George Beadle.

Unlocking Chromosome Mysteries

McClintock's research focused on finding ways to see and understand corn chromosomes. Her methods were so good that they were included in many textbooks. She developed a special staining technique to make the 10 corn chromosomes visible. This allowed her to see their shapes for the first time.

By studying the chromosome shapes, she could connect specific chromosome parts to traits that were passed down together. In 1930, she was the first to describe how chromosomes interact during cell division. The next year, she and Harriet Creighton proved that when chromosomes swap information, new traits appear. This was a huge discovery!

In 1931, McClintock also created the first genetic map for corn. This map showed the order of three genes on corn chromosome 9. Later, in 1938, she studied the centromere, a part of the chromosome important for cell division.

Her amazing work earned her several special research grants. This allowed her to continue her studies at Cornell, the University of Missouri, and the California Institute of Technology. She even worked with Lewis Stadler, who taught her how to use X-rays to create changes in genes. This helped her discover ring chromosomes and understand how chromosome ends (called telomeres) protect genetic information.

In 1933, she traveled to Germany for six months to train. But she left early because of the rising political tensions in Europe. When she returned to Cornell, she found that the university would not hire a woman professor. So, in 1936, she accepted a teaching job at the University of Missouri.

Moving Forward: Missouri and Cold Spring Harbor

New Discoveries in Missouri

At the University of Missouri, McClintock continued her research on how X-rays affect corn chromosomes. She saw that chromosomes could break and then rejoin in irradiated corn cells. She also found that in some plants, chromosomes could break on their own.

She observed a cycle where broken chromosome ends would rejoin after DNA copied itself. This cycle caused many changes in the corn plants, which she could see as color variations in the corn kernels. This "breakage–rejoining–bridge cycle" was a key discovery. It showed that chromosomes don't rejoin randomly and that this process can cause big genetic changes. Today, this cycle is still studied in cancer research.

Even though her research was going well, McClintock was not happy at Missouri. She felt left out of faculty meetings and wasn't told about job openings elsewhere. She believed she wouldn't get a permanent position there. In 1941, she took a break from Missouri to find another job.

A Home for Research at Cold Spring Harbor

She accepted a visiting professor position at Columbia University. Her former Cornell colleague, Marcus Rhoades, was there. He also offered her space to work at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island. In December 1941, she was offered a permanent research position at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. She accepted and became a full-time member of the team.

At Cold Spring Harbor, McClintock was very productive. She continued her work with the breakage-fusion-bridge cycle. In 1944, she was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. She was only the third woman ever to receive this honor. The next year, she became the first female president of the Genetics Society of America.

She also studied a fungus called Neurospora crassa. She successfully described its chromosomes and life cycle. Another scientist, George Beadle, said that Barbara did more to understand the fungus's cells in two months than all other scientists had done before! This fungus is now a very important model organism for genetic studies.

Her Big Idea: Jumping Genes!

How Genes Can Move

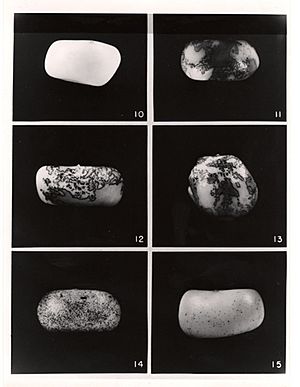

In 1944, McClintock began studying the changing color patterns in corn kernels. She found two new interacting genetic parts she called Dissociation (Ds) and Activator (Ac). She noticed that Ds didn't just break chromosomes. It also affected nearby genes when Ac was present.

In 1948, she made a surprising discovery: both Ds and Ac could "transpose," or change their position, on the chromosome! She saw how the movement of Ac and Ds changed the color patterns in corn kernels over many generations. She used careful microscopic analysis to understand this.

She figured out that Ac controls the movement of Ds. When Ds moves, a gene that makes color is "turned on," creating pigment in the cells. The movement of Ds happens randomly in different cells, which causes the mosaic (patchy) color patterns. The size of the colored spots depends on when the movement happens during the corn seed's growth. She also found that the number of Ac copies in a cell affects how Ds moves.

Why This Idea Was So Important

Between 1948 and 1950, McClintock developed a theory. She believed these mobile elements controlled genes by turning them on or off. She called them "controlling units" or "controlling elements." She thought that this "gene regulation" could explain how complex living things, with cells that have the same genetic information, can have cells that do different jobs (like a heart cell versus a skin cell).

McClintock's discovery challenged the old idea that genes were always in a fixed place. In 1950, she published her work on Ac/Ds and her ideas about gene regulation. She also talked about her work at a big science meeting in 1951.

Her ideas about controlling elements were very new and hard for other scientists to understand. She said the reaction to her research was "puzzlement, even hostility." But McClintock kept working on her ideas. She published more data in 1953 and gave many lectures. She even found a new element called Suppressor-mutator (Spm).

Because other scientists were so doubtful, McClintock felt she might be pushed away from the main scientific community. So, after 1953, she stopped publishing her research on controlling elements for a while.

Later Work and Recognition

Studying Corn's History

In 1957, McClintock received money to study different types of corn in Central and South America. She wanted to understand how corn had changed over time by looking at its chromosomes. She studied the chromosomes, shapes, and evolution of many corn varieties.

After a lot of work in the 1960s and 1970s, McClintock and her helpers published an important study. It was called The Chromosomal Constitution of Races of Maize. This work was very important for understanding ancient plants, how people used plants, and how living things change over time.

When Her Ideas Were Finally Understood

McClintock officially retired in 1967. But she continued to work with students and colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory as a "scientist emerita." She lived in the town nearby.

The importance of McClintock's work became clear in the 1960s. This happened when other scientists, like French geneticists François Jacob and Jacques Monod, described how genes are regulated in bacteria. This was similar to what McClintock had shown with her "controlling elements" in corn back in 1951.

McClintock finally received widespread credit for discovering "transposition" in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This was when other researchers found similar "jumping genes" in bacteria, yeast, and viruses. New technology in molecular biology helped scientists see exactly how these elements moved.

Later research showed that these "transposons" usually only move when a cell is under stress. This means their movement can help create new genetic variations, which is important for evolution. McClintock understood this role of transposons long before other scientists did. Today, her Ac/Ds elements are used as tools in plant biology to study gene function.

Awards and Honors

McClintock received many awards for her amazing work. In 1947, she got the Achievement Award from the American Association of University Women. She became a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1959.

In 1970, she received the National Medal of Science from President Richard Nixon. She was the first woman to ever receive this medal. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory named a building after her in 1973.

She received many other awards, including the first MacArthur Foundation Grant in 1981. She also won the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research and the Wolf Prize in Medicine.

Most importantly, she received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983. She was the first woman to win this prize by herself, and the first American woman to win any unshared Nobel Prize. She won it for discovering "mobile genetic elements" – her "jumping genes." This was more than 30 years after she first described them! The Swedish Academy of Sciences compared her scientific career to that of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics.

In 1989, she became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in Britain. She also received 14 honorary doctorates from universities. In 1986, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame. In her later years, McClintock became more well-known, especially after a biography about her was published in 1983. She continued to give talks at Cold Spring Harbor, sharing her knowledge with younger scientists.

The McClintock Prize is named in her honor, given to other scientists who make important discoveries in genetics.

Her Lasting Legacy

A Role Model for Scientists

McClintock spent her final years as a key researcher at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. She passed away on September 2, 1992, at the age of 90. She never married or had children.

A biography about her, A Feeling for the Organism, was published in 1983. The author suggested that because McClintock sometimes felt like an outsider in science, she could see things differently. This led to her important discoveries. However, some colleagues didn't accept her ideas at first. For example, one geneticist thought she didn't understand math, a belief he also held about other women scientists.

Another biography in 2001, The Tangled Field, suggested that McClintock was not always discriminated against. It argued that she was well-respected by her peers, even early in her career.

Many books about women in science feature McClintock's work and experiences. She is seen as a role model for girls. Books like Barbara McClintock, Nobel Prize Geneticist and Barbara McClintock: Alone in Her Field tell her story for young readers.

How We Remember Her

On May 4, 2005, the United States Postal Service released stamps honoring American scientists. Barbara McClintock was one of the four scientists featured. She was also on a Swedish stamp in 1989, which showed the work of Nobel Prize-winning geneticists.

A small building at Cornell University and a laboratory building at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory are named after her. A street in Berlin, Germany, is also named after her. Barbara McClintock Hall, a student residence at Cornell University, honors her memory.

Her personality and scientific achievements were even mentioned in a 2011 novel called The Marriage Plot. A play about McClintock, called MAIZE, was performed in 2015 and 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Barbara McClintock para niños

In Spanish: Barbara McClintock para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |