History of the Burgess Shale facts for kids

The Burgess Shale is a famous place in the Canadian Rockies. It has many amazing fossils. These fossils show us what life was like millions of years ago.

Richard McConnell first saw these fossil beds in 1886. He worked for the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). Later, a scientist named Charles Doolittle Walcott heard about these finds. He visited the area in 1907.

Walcott started a fossil quarry in 1910. He collected 65,000 fossils from this site. He figured out these fossils were from the Middle Cambrian period. This was a time when many new animals appeared on Earth.

Walcott was very busy at the Smithsonian Institution. He could only publish short papers about his finds. He tried to fit the new fossils into animal groups already known.

Later, in 1924, Percy Raymond from Harvard University collected more fossils. He found them in Walcott's quarry and higher up on Fossil Ridge. These new fossils were a bit different.

Contents

Discovering Ancient Life: The Burgess Shale Story

After Raymond's trips in the 1930s, interest in the Burgess Shale slowed down. But in the 1960s, Harry B. Whittington thought more study was needed. He worked with the Geological Survey of Canada.

Whittington's team looked at Walcott's old fossils. These had been stored away since Walcott died in 1927. In the early 1970s, the team published new findings. They said many fossils were from unknown types of animals. Some might even be new phyla, which are major animal groups.

These discoveries made people wonder about the Cambrian explosion. Did many animals suddenly appear? Or did they develop slowly, with many fossils still hidden? The Burgess Shale helped answer these big questions.

Early Fossil Hunts in the Rockies

Workers building the Trans-Canada railway first found many fossils. This railway went through the Kicking Horse valley. In 1886, Richard McConnell was mapping the area. A railway worker showed him the Mount Stephen trilobite beds.

Scientists later described strange fossils from this spot. These included sponges, worms, and parts of the unusual Anomalocaris. At first, Anomalocaris parts were thought to be crab bodies. Some of these fossils went to Charles Doolittle Walcott. He studied them and correctly guessed their age. These finds made Walcott very keen to visit the area himself. He finally got the chance in 1907.

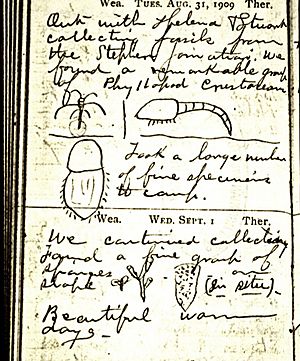

In 1908, Walcott published many papers about his 1907 finds. He returned to the Field area in August 1909. That summer, he had visited England. There, a museum curator suggested that Mount Field might have more fossils like the Trilobite beds.

When Walcott arrived in Field, he climbed Mount Field. He went along what is now called Fossil Ridge. He saw interesting fossils in the rocks there. This is often seen as the first discovery of the main Burgess Shale site. He spent more days collecting fossils on Fossil Ridge. Then he went back to Mount Stephen to get more from the Trilobite Beds.

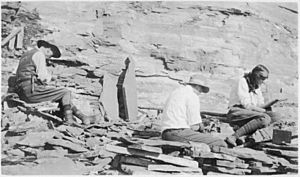

The next year, Walcott collected even more fossils. He and his two sons searched every rock layer. They wanted to find where the best fossils came from. They found the rich layers, including the Phyllopod bed. This became known as the Walcott Quarry.

They dug out large rock blocks. They sent them by horse to Walcott's wife. She would split the shale to prepare the fossils. Then they were sent down the mountain to Field, and by train to Washington. In 1911, Walcott first used the name 'Burgess Shale'. He described many animal types that are now well-known. However, many of his early classifications would later be changed. These were Walcott's last papers focused on Burgess Shale animals.

Walcott and his family returned to the quarry every summer until 1913. They even used dynamite to find more fossils. Walcott felt his 1917 trip had "practically exhausted" the quarry. That year, they collected 1300 kg of material. He returned for more collections in 1919, 1921, and 1924. He gathered 65,000 fossil specimens on 30,000 rock slabs. During these years, he also described sponges and algae. He planned to describe many more animals, but his other duties grew. The Burgess Shale work became less of a priority.

Three years before Walcott died in 1927, Percy Raymond from Harvard University visited. He brought summer-school students to Walcott's camp. Raymond became very interested in the fossils. He got permission to reopen the quarry. He also found a new layer higher up the slope. This layer had slightly different animals. He opened a new quarry there, now called the Raymond Quarry.

New Discoveries and Renewed Interest

After Raymond's trips, the Burgess Shale was not studied much for a while. Harry Whittington helped bring new attention to the site. He realized that Walcott's old collections needed to be studied again. He convinced the Geological Survey of Canada to revisit the area.

Whittington, an expert on trilobites, led the new fossil hunts. In 1966, he went with Jim Aitken and Bill Fritz. In 1967, David Bruton joined them. They carefully collected large rock slabs from the Walcott and Raymond quarries. These were labeled and flown by helicopter to Whittington's lab in Cambridge.

The 1967 work led to descriptions of new animals. These included the earliest known crinoid and a complete Anomalocaris. They also studied common arthropod-like animals like Marrella, Sidneyia, and Burgessia.

It became clear that the Burgess Shale was very special. Soft body parts were preserved in amazing detail. This gave scientists clues about early life never seen before. It showed many animals that don't usually leave fossils.

The Burgess Shale had so many different animals. Harry Whittington asked his students, Derek Briggs and Simon Conway Morris, to help. They studied the arthropods and 'worms'. Their work showed an incredibly diverse ancient ecosystem. It had almost as much variety as today's oceans. The old idea that Cambrian life was simple quickly changed. This was also supported by finding similar fossil sites around the world.

In 2014, a new Burgess Shale site was found in Kootenay National Park. In just 15 days, scientists found 50 new animal species there!

Canada's Own Fossil Collections

Until 1975, no Canadian museum had its own Burgess Shale fossils. As the shale became more famous, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) got permission to collect fossils. They collected from loose rock material to create their own displays.

The ROM's first trip in 1975 collected 7,750 specimens. They also found signs of more fossil sites higher up the mountain. In 1981, they started a five-year program to explore these new areas.

This program found more sites on Fossil Ridge, Mount Stephen, and Odaray Mountain. These new sites were very productive. They had different animals and covered a longer time period. ROM teams still dig for fossils today. They have found fossils below Walcott's quarry. They also found some 40 km away near the Stanley Glacier.

The ROM now has over 140,000 specimens. They keep finding important new species. Scientists believe new species will continue to be discovered for many years.

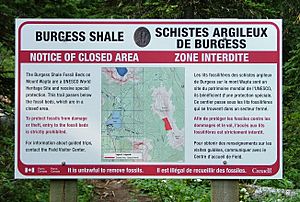

Protecting This Special Place

In 1981, UNESCO recognized the Burgess Shale's importance. They named it a World Heritage Site. Now, you can only visit the Fossil Ridge quarries and Trilobite beds with a guided group. Parks Canada watches over the sites. There are big fines for taking or damaging any fossils.

Celebrating 100 Years of Discovery

In August 2009, scientists celebrated 100 years since Walcott's main discovery. An international conference was held in Banff, Alberta. About 150 experts came together. They shared the latest research and took hikes to the Burgess Shale itself.