Anomalocaris facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Anomalocaris |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| A complete fossil specimen of Anomalocaris canadensis | |

|

|

| An artist's drawing of what Anomalocaris canadensis might have looked like | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Dinocaridida |

| Order: | †Radiodonta |

| Family: | †Anomalocarididae |

| Genus: | †Anomalocaris Whiteaves, 1892 |

| Species | |

(8 more unnamed species) |

|

Anomalocaris was an amazing creature that lived in the ocean over 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period. Its name comes from Greek words meaning "unlike other shrimp," because its first fossil looked very strange to scientists. It was an early type of arthropod, making it a distant relative of modern insects, spiders, and crabs.

Anomalocaris was one of the largest animals of its time. It had a long, segmented body with flaps on the sides that it used for swimming. It also had large, complex eyes on stalks and two spiky arms at the front of its head for catching prey. For many years, scientists believed Anomalocaris was one of the first apex predators, an animal at the top of the food chain with no predators of its own.

When its fossils were first discovered, scientists were very confused. They found different body parts separately and thought they belonged to different animals. It took almost 100 years for them to piece the puzzle together and realize all the parts belonged to one incredible creature.

Contents

A Scientific Puzzle

The story of how Anomalocaris was discovered is a famous example of how science works, with mistakes and corrections leading to a big discovery. The writer Stephen Jay Gould described it as a "tale of humor, error, struggle, frustration, and more error, culminating in an extraordinary resolution."

Mismatched Pieces

The first fossils of Anomalocaris were found in Canada in the late 1800s. But scientists only found the two front arms. They thought these arms were the body of a shrimp-like creature, which is why they named it Anomalocaris, or "strange shrimp."

Around the same time, other scientists found different fossils that they couldn't identify.

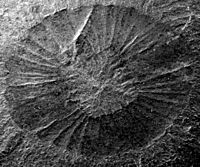

- A circular, pineapple-slice-shaped fossil was thought to be a type of jellyfish and was named Peytoia.

- Another fossil of a body with swimming flaps was thought to be a sea cucumber and was named Laggania.

For decades, no one knew that these three "animals"—the shrimp tail (Anomalocaris), the jellyfish (Peytoia), and the sea cucumber (Laggania)—were actually all parts of the same creature.

Solving the Mystery

The puzzle was finally solved in the 1980s. A team of paleontologists led by Harry B. Whittington was re-examining fossils from a famous site in Canada called the Burgess Shale. While cleaning a fossil, a researcher uncovered a specimen that clearly showed the "shrimp tail" arm attached to the front of a body, right next to the "jellyfish" mouth.

They realized that Anomalocaris was not a shrimp's body, but a grasping arm. The Peytoia jellyfish was its circular mouth, and Laggania was its body. They had finally put the pieces together to reveal a single, large, and fearsome predator. The name Anomalocaris was kept for this amazing animal.

What Did Anomalocaris Look Like?

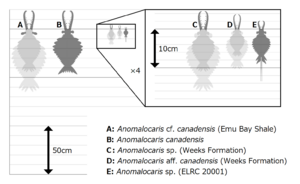

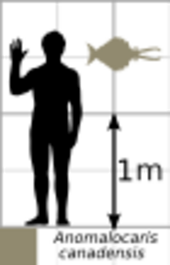

Anomalocaris was a giant in the Cambrian seas. While most animals at the time were only a few centimeters long, Anomalocaris could grow to be over 38 cm (more than a foot) long, not including its arms and tail. Some related species may have been even larger.

Swimming and Body

Anomalocaris moved through the water by waving the flexible flaps on the sides of its body. It had at least 13 pairs of these flaps. By moving them in a wave-like motion, it could swim smoothly and gracefully. Scientists even built a robot model to show that this way of swimming was very stable and efficient. At the back of its body, it had a tail fan that it likely used for steering, like a rudder on a boat.

Super Sight

One of the most impressive features of Anomalocaris was its eyes. It had two large compound eyes on stalks, similar to the eyes of a modern dragonfly. Fossils found in Australia show that each eye could have had over 24,000 lenses. This would have given Anomalocaris incredibly sharp vision, much better than that of trilobites, which were long thought to have the best eyes of the Cambrian period. This excellent eyesight would have made it a very effective hunter.

Mouth and Claws

The mouth of Anomalocaris was a unique, circular structure made of hard plates with sharp points facing inward. It looked a bit like a slice of pineapple. In front of the mouth were two large, spiky arms. Each arm was made of 14 segments and had sharp spines along its length. Anomalocaris would have used these arms to grab its prey and hold it while it ate.

A Top Hunter of the Cambrian Seas

With its large size, powerful swimming, sharp vision, and spiky arms, Anomalocaris was almost certainly an apex predator. It was at the top of the food chain and likely hunted many of the other animals living in the Cambrian oceans.

What Was on the Menu?

For a long time, scientists thought that Anomalocaris ate hard-shelled animals like trilobites. Some trilobite fossils have been found with W-shaped scars that looked like bite marks from a creature like Anomalocaris. Also, large fossilized droppings (called coprolites) containing trilobite pieces have been found, and Anomalocaris was one of the few animals big enough to have made them.

However, some scientists now question this idea. Studies of its mouth suggest it may not have been strong enough to crush hard trilobite shells. The arms also don't show much wear and tear, which you might expect if they were used to break open hard prey.

A Hunter of Soft Prey?

A newer theory is that Anomalocaris hunted soft-bodied animals. Its mouth might have worked more like a suction cup, pulling in soft prey. It could have easily hunted other free-swimming arthropods, worms, or other creatures that didn't have hard shells. It would have used its long arms to snatch these animals out of the water while swimming at high speed. The debate over its exact diet shows that there are still many mysteries to solve about life in the ancient past.

Where Did It Live?

Anomalocaris was a very successful animal and lived all over the world. Its fossils have been found in rocks from the Cambrian period in:

- Canada, especially in the famous Burgess Shale.

- China, in areas like the Chengjiang Biota.

- Australia, in a fossil site called the Emu Bay Shale.

- The United States, in states like Utah and Nevada.

Finding Anomalocaris in so many different places shows that it was widespread and well-adapted to the shallow, warm oceans of the Cambrian world.

See Also

In Spanish: Anomalocaris para niños

In Spanish: Anomalocaris para niños

- 8564 Anomalocaris, an asteroid named after this animal.

- Radiodonta, extinct arthropod order composed of Anomalocaris and its relatives.

- Houcaris, Lenisicaris, Innovatiocaris, Guanshancaris, Echidnacaris, radiodont genera containing species originally named as Anomalocaris.

- Aegirocassis, a giant filter-feeding radiodont from Ordovician Morocco.

- Cambrian explosion, the large bio-diversification event that occurred during the Cambrian.

- Opabinia, a genus of bizarre stem-group arthropod distantly related to the radiodonts.

- Wiwaxia, a genus of possible mollusk that had copious numbers of carbonaceous scales, and lived alongside Anomalocaris.

- Paleobiota of the Burgess Shale