Hoopoe starling facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hoopoe starling |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Specimen in Musée Cantonal de Zoologie, Lausanne | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sturnidae |

| Genus: | †Fregilupus Lesson, 1831 |

| Species: |

†F. varius

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Fregilupus varius (Boddaert, 1783)

|

|

|

|

| Location of Réunion (circled) | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

Upupa varia Boddaert, 1783

Upupa capensis Gmelin, 1788 Upupa madagascariensis Shaw, 1811 Coracia cristata Vieillot, 1817 Pastor upupa Wagler, 1827 Fregilupus capensis Lesson, 1831 Coracia tinouch Hartlaub, 1861 Fregilupus borbonicus Vinson, 1868 Fregilupus varia Gray, 1870 Sturnus capensis Schlegel, 1872 Lophopsarus varius Sundeval, 1872 Coracias tivouch Murie, 1874 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The hoopoe starling (Fregilupus varius) was a type of starling bird. It lived on the island of Réunion, which is part of the Mascarene Islands. Sadly, this bird became extinct around the 1850s. It was also known as the Réunion starling or Bourbon crested starling.

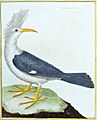

This bird was about 30 centimeters (12 inches) long. Its feathers were mostly white and grey. Its back, wings, and tail were a darker brown and grey. It had a special light crest of feathers on its head that curled forward. Males might have been larger with more curved beaks. Young birds were browner than adults.

Hoopoe starlings lived in large groups in wet areas and marshes. They ate both plants and insects. Their strong legs and beaks suggest they looked for food near the ground. Settlers on Réunion hunted these birds and also kept them as pets. The last hoopoe starling was likely gone before the 1860s. Many things led to their extinction, like new animals, diseases, and people hunting them.

Contents

Discovering the Hoopoe Starling

The hoopoe starling was first mentioned in the 1600s. A French governor named Étienne de Flacourt wrote about a "tivouch" bird in 1658. Later, in 1669, Père Vachet noted the bird on Réunion Island.

The first detailed description came from French traveler Sieur Dubois in 1674. He called them "Hoopoes or 'Calandres'". He said they had a white tuft on their heads. The rest of their feathers were white and grey. Their beaks and feet were like a bird of prey. He also noted they were good to eat.

Early settlers called the bird "huppe" because its crest and curved beak looked like a hoopoe bird. For about 100 years, not much was written about them. But in the 1700s, some birds were sent to Europe.

Giving the Bird a Scientific Name

The hoopoe starling was first described scientifically in 1779. This was in a book by Comte de Buffon called Histoire Naturelle. In 1783, Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert gave it its scientific name, Upupa varia. The name Upupa is for the hoopoe bird. Varia means "variegated," which describes its black and white colors.

The 1770s drawing of the bird by François-Nicolas Martinet is very important. It is considered the first official drawing of the species. The National Museum of Natural History in Paris had some hoopoe starling skins. One of these skins might have been used for Martinet's drawing.

For a long time, people thought this bird was related to the hoopoe. Some even thought it lived in Madagascar or Africa. It was given many different scientific names. But in 1831, French naturalist René-Primevère Lesson put it in its own special group, Fregilipus. This name combines "Upupa" (hoopoe) and "Fregilus" (an old name for a chough bird).

Confirming it's a Starling

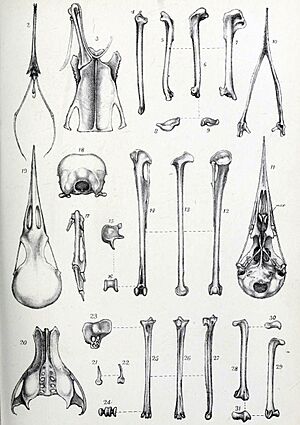

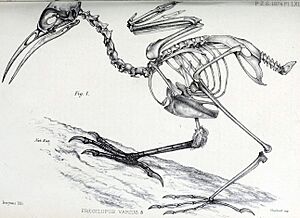

In 1857, German ornithologist Hermann Schlegel first suggested the bird was a starling. He placed it in the Sturnus genus. Other scientists agreed with this idea. In 1874, British zoologist James Murie studied the only known skeleton of the bird. He also confirmed it was a starling.

In 2008, scientists did a DNA study on different starlings. This study finally confirmed that the hoopoe starling was indeed a starling. It was part of a group of starlings from Southeast Asia. This means its ancestors probably came from that region. They might have traveled across the Indian Ocean by stopping at different islands.

What the Hoopoe Starling Looked Like

The hoopoe starling was about 30 centimeters (12 inches) long. Its beak was about 41 millimeters (1.6 inches) long. Its wing was about 147 millimeters (5.8 inches) and its tail was about 114 millimeters (4.5 inches). It was the biggest of the three starling species from the Mascarene Islands.

An adult male bird had a light ash-grey head and neck. It had a long crest of feathers that was the same color. Its back and tail were ash-brown. Its wings were darker with a greyish tint. The feathers under its tail were a reddish-brown color. Its belly was white, sometimes with a pale reddish-brown wash.

The beak and legs of the bird were lemon-yellow. Its claws were yellow-brown. It had a bare, triangular patch of skin around its eye. This skin was likely yellow when the bird was alive. Its eye color was described as bluish-brown, but drawings show it as brown, yellow, or orange.

Differences Between Males and Females

It's hard to know for sure how males and females differed. Only three specimens were identified as male. Males are thought to have been larger with longer, more curved beaks. One female specimen seems to have had a smaller crest and a smaller, less curved beak.

Young hoopoe starlings had a smaller crest. Their crest, face, and back were more brownish than the adults. This is similar to how young starlings in Southeast Asia look.

People who saw live hoopoe starlings said their crest was very flexible. It had feathers of different lengths that curled forward. The bird could raise its crest whenever it wanted. It was compared to the crest of a cockatoo. Most museum specimens have their crest standing up, which shows how it naturally looked.

The only known drawing of a live hoopoe starling was made by French artist Paul Philippe Sauguin de Jossigny in the early 1770s. He told engravers to draw the crest angled forward, not straight up.

Life and Habitat

Not much is known about how the hoopoe starling behaved. In 1807, François Levaillant wrote that the bird was common. Large groups lived in wet areas and marshes. In 1831, Lesson said its habits were like those of a crow.

Its song was described as a "bright and cheerful whistle." It had "clear notes," similar to other starlings. One person who saw them in the 1800s said they flew in groups in the rain forests. They ate berries, seeds, and insects. People on the island thought they were "impure" because they ate insects.

Sometimes, they would fly from the woods to the coast. They would land in large groups on coffee trees. Some people thought they damaged coffee trees by making flowers fall. But it's believed they were actually looking for caterpillars and insects on the trees. This means they were helping the coffee farms!

Like most starlings, the hoopoe starling ate many different things. Its diet included fruits, seeds, and insects. Its tongue was long and slender, which helped it eat fruit, nectar, and insects. Its strong legs and feet suggest it looked for food on the ground. Its strong jaws might have helped it probe and open holes in the ground to find food.

One bird's stomach was found to contain seeds and berries. The bird was heaviest around June and July. Some reports say the hoopoe starling moved around Réunion Island. It spent six months in the lowlands and six months in the mountains. They might have found more food in the lowlands during winter. They probably nested in tree holes in the mountain forests during summer.

The hoopoe starling lived alongside other unique birds on Réunion. Many of these birds also became extinct after humans arrived. These included the Réunion ibis and the Réunion parakeet.

Why the Hoopoe Starling Disappeared

The hoopoe starling was known to be tame and easy to hunt. In 1704, Jean Feuilley wrote about how people and even cats caught them. He said they were very easy to approach.

People on Réunion and Mauritius also kept them as pets. Even though the birds were becoming rare, some were still caught in the early 1800s. It's not known if any live birds were ever taken off the islands. Some birds escaped on Mauritius, but they didn't survive long. The last known hoopoe starling was seen in 1836 on Mauritius. Birds could still be found on Réunion in the 1830s and early 1840s.

Today, there are nineteen hoopoe starling specimens in museums around the world. This includes one skeleton and two birds preserved in liquid. Some skins were lost during World War II. Most specimens were collected in the early 1800s. In 1993, a leg bone (femur) of a hoopoe starling was found in a cave on Réunion. This is the only known fossil of the bird.

The Extinction Story

Many reasons are suggested for the hoopoe starling's extinction. All of them are linked to human activities on Réunion. The bird lived alongside humans for about 200 years.

One idea is that the introduction of the common myna bird caused problems. Mynas were brought to Réunion in 1759 to control locusts. But they became a pest themselves. However, the hoopoe starling lived with mynas for almost 100 years, so they might not have competed directly.

Rats also arrived on Réunion in the 1600s and 1700s. They multiplied quickly and were a threat to native species. Like the hoopoe starling, rats lived in tree holes. They would have eaten the birds' eggs, young, and nesting adults.

Diseases from introduced birds might have also affected the hoopoe starling. This is known to have caused extinctions in other island birds. Some experts believe disease was the main reason for the hoopoe starling's extinction.

Starting in the 1830s, much of Réunion's forests were cut down for farms. This pushed the hoopoe starling out of its home. Hunting also played a big role. As more people lived on the island, hunting increased. The bird was hunted for food and because people thought it damaged crops. In 1821, a law was even made to kill birds that damaged grain.

By the 1860s, writers noted that the bird had almost disappeared. It was probably already extinct by then. There were no known attempts to breed the birds in captivity to save them.

The hoopoe starling survived longer than many other extinct birds from the Mascarene Islands. It was the last of the Mascarene starlings to disappear. The other two starling species from nearby islands probably died out when rats arrived. The hoopoe starling might have survived longer because Réunion has rugged mountains. It spent much of the year in these highlands.

Images for kids

-

Specimen in Musée Cantonal de Zoologie, Lausanne

-

Location of Réunion (circled)

-

1770s type illustration by François-Nicolas Martinet

-

Specimen in National Museum of Natural History, Paris, with a similar crest

-

1874 lithographs of the only known skeleton