Averroes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Averroes

Ibn Rushd |

|

|---|---|

Statue of Averroes in Córdoba, Spain

|

|

| Born | 14 April 1126 |

| Died | 11 December 1198 (aged 72) |

| Other names | Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad ibn Rushd The Commentator |

| Era | Medieval, Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Islamic philosophy |

| School | Aristotelianism |

|

Main interests

|

Islamic theology, philosophy, Islamic jurisprudence, medicine, astronomy, physics, linguistics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Relation between Islam and philosophy, non-contradiction of reason and revelation, unity of the intellect |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

See also Averroism. |

|

Ibn Rushd (Arabic: ابن رشد; full name in Arabic: أبو الوليد محمد ابن احمد ابن رشد, romanized: Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad Ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rušd; 14 April 1126 – 11 December 1198), often called Averroes (English: /əˈvɛroʊiːz/), was a very smart person from Al-Andalus (what is now Spain). He was a polymath, meaning he knew a lot about many different subjects. He wrote about philosophy, theology (the study of religion), medicine, astronomy, physics, and law.

Averroes wrote over 100 books! Many of his most famous works were detailed explanations of the writings of Aristotle, an ancient Greek philosopher. Because of these commentaries, people in the Western world called him The Commentator. He is also known as the Father of Rationalism, which means he believed in using reason and logic to understand the world.

Averroes strongly supported Aristotle's ideas. He tried to bring back Aristotle's original teachings. He also defended philosophy against critics who thought it went against Islamic beliefs. Averroes argued that philosophy was allowed in Islam. He even said it was important for some people to study it. He believed that if religious texts seemed to disagree with what reason told us, then the texts should be understood in a deeper, symbolic way.

In medicine, Averroes had new ideas about stroke. He was also the first to describe the signs of Parkinson's disease. He might have been the first to realize that the retina is the part of the eye that sees light. His medical book, Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb, was translated into Latin and used as a textbook in Europe for hundreds of years.

Averroes's ideas were very important in Europe. His translations of Aristotle's works helped people in Western Europe become interested in ancient Greek thinkers again. This interest had faded after the fall of the Roman Empire. His ideas led to a philosophical movement called Averroism. However, his works were also criticized by the Catholic Church in the late 1200s.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Averroes's full Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, people added "al-Hafid" (meaning "The Grandson") to his name. This was to tell him apart from his grandfather, who was also a famous judge.

The name "Averroes" is the Latin version of "Ibn Rushd". It came from how the Spanish pronounced his Arabic name. There are many other ways his name was written in European languages over time.

Averroes's Life

Early Years and Learning

Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd was born on April 14, 1126, in Córdoba. His family was well-known for serving the public, especially in law and religion. His grandfather was the chief judge of Córdoba. His father was also a chief judge for a time.

Averroes had an excellent education. He studied Islamic traditions (hadith), Islamic law (fiqh), medicine, and theology. He learned from many teachers. He also knew the works of other philosophers. He attended meetings with philosophers, doctors, and poets. He was very good at understanding different opinions in Islamic law. He was also interested in "the sciences of the ancients," which meant Greek philosophy and science.

His Career

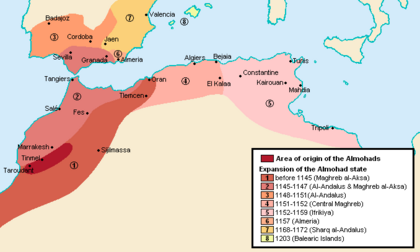

By 1153, Averroes was in Marrakesh, the capital city of the Almohad Caliphate (in modern-day Morocco). He was there to study the stars and help build new colleges. He wanted to find physical rules for how planets moved. He also met Ibn Tufayl, a famous philosopher and doctor. They became good friends.

In 1169, Ibn Tufayl introduced Averroes to the caliph, Abu Yaqub Yusuf. The caliph asked Averroes a difficult question about whether the heavens had always existed. Averroes was careful with his answer. The caliph then showed how much he knew about philosophy, which impressed Averroes. Averroes then shared his own ideas, which also impressed the caliph.

Averroes stayed in the caliph's favor until the caliph died in 1184. The caliph found Aristotle's writings hard to understand. So, Ibn Tufayl suggested that Averroes write explanations. This is how Averroes started his huge project of writing commentaries on Aristotle. His first works on this topic were written in 1169.

In the same year, Averroes became a judge (qadi) in Seville. In 1171, he became a judge in his hometown of Córdoba. As a judge, he made decisions in cases and gave legal opinions based on Islamic law. He wrote a lot during this time, even with his busy job and travels. In 1182, he became the court physician, taking over from his friend Ibn Tufayl. Later that year, he became the chief judge of Córdoba, a very important job his grandfather once held.

In 1184, Caliph Abu Yaqub died, and his son Abu Yusuf Yaqub took over. At first, Averroes remained popular with the new caliph. But in 1195, things changed. He was accused of various things, and his teachings were condemned. His books were ordered to be burned, and he was sent away to a town called Lucena. Modern historians believe this happened for political reasons. The caliph might have wanted to gain support from religious scholars who didn't like Averroes's ideas.

After a few years, Averroes was allowed to return to court in Marrakesh. He died soon after, on December 11, 1198. He was first buried in North Africa, but his body was later moved to Córdoba.

Averroes's Writings

Averroes wrote a huge number of books. He covered many subjects like philosophy, medicine, law, and language. Most of his writings were commentaries, which means they were explanations or summaries of other works, especially those by Aristotle. But these commentaries also contained many of Averroes's own original ideas.

He wrote at least 67 original works. These included 28 books on philosophy, 20 on medicine, 8 on law, and 5 on theology. Many of his Arabic writings have been lost over time. However, their translations into Hebrew or Latin still exist.

Explaining Aristotle

Averroes wrote explanations for almost all of Aristotle's surviving works. He didn't have Aristotle's book on Politics, so he wrote a commentary on Plato's Republic instead.

He divided his commentaries into three types:

- Short commentaries: These were summaries of Aristotle's ideas, often written early in Averroes's career.

- Middle commentaries: These were simpler explanations of Aristotle's texts. He probably wrote these to help people, including the caliph, understand Aristotle better.

- Long commentaries: These were very detailed, line-by-line analyses of Aristotle's original works. They contained many of Averroes's own deep thoughts. These were likely for advanced readers.

Only five of Aristotle's works had all three types of commentaries: Physics, Metaphysics, On the Soul, On the Heavens, and Posterior Analytics.

His Own Philosophical Works

Averroes also wrote his own philosophical books. Some titles include On the Intellect, On the Syllogism, and On Time. He also wrote arguments against the ideas of other philosophers like Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

Islamic Theology

Averroes wrote important works on Islamic theology (the study of religious beliefs).

- Fasl al-Maqal ("The Decisive Treatise") was written in 1178. In this book, he argued that Islam and philosophy could exist together without problems.

- Al-Kashf 'an Manahij al-Adillah ("Exposition of the Methods of Proof"), written in 1179, criticized other theological ideas. It explained Averroes's own arguments for God's existence and God's qualities.

- Tahafut al-Tahafut ("Incoherence of the Incoherence"), from 1180, was his response to Al-Ghazali's famous book, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, which criticized philosophy. Averroes used his own ideas to defend philosophy against Al-Ghazali's arguments.

Medical Writings

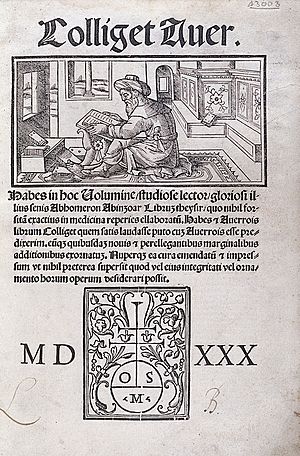

Averroes was a royal physician, and he wrote several medical books. His most famous was al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb ("The General Principles of Medicine"). In Europe, it was known as the Colliget. This book became a standard medical textbook for centuries.

He also wrote about specific medical topics like "On Treacle" (a medicine) and "Medicinal Herbs." He summarized the works of the Greek physician Galen and commented on a medical poem by Avicenna.

Law and Justice

Averroes worked as a judge for many years and wrote several books on Islamic law. His only surviving book on this topic is Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa Nihāyat al-Muqtaṣid ("Primer of the Discretionary Scholar"). In this book, he explained why there were different opinions among the various schools of Islamic law. He showed that these differences were natural and came from how scholars interpreted religious texts and used logic.

Averroes's Ideas

Philosophy and Aristotle

Averroes believed that earlier Muslim philosophers had changed Aristotle's ideas too much by adding Neoplatonic thoughts. He wanted to go back to Aristotle's original teachings. He pointed out the differences between Plato and Aristotle. For example, Aristotle did not believe in Plato's "theory of ideas." Averroes also strongly criticized Avicenna, who was a leading Neoplatonic thinker.

Averroes felt it was important to include Greek ideas in the Muslim world. He wrote that if someone before us had studied wisdom, we should learn from what they said, no matter their background.

Religion and Philosophy

During Averroes's time, philosophy was often criticized by some Islamic religious groups. A famous scholar named Al-Ghazali wrote a strong book called The Incoherence of the Philosophers, which attacked philosophy. He even accused philosophers of not believing in Islam.

In his book Decisive Treatise, Averroes argued that philosophy and Islam cannot disagree. He said they are just two different ways to find the truth, and "truth cannot contradict truth." If philosophy seemed to go against a religious text, Averroes believed the text should be understood in a deeper, symbolic way. He said that the Quran itself encourages Muslims to study nature and use reason. This would help them learn more about God. He even gave a legal opinion (fatwa) that studying philosophy was allowed for Muslims, and perhaps even required for those who were good at it.

Averroes also explained that there are different ways to talk about truth:

- Rhetorical: This uses persuasion and is for everyone.

- Dialectical: This uses debate and is for scholars.

- Demonstrative: This uses logical proof and is for philosophers.

He said the Quran uses the rhetorical method to reach everyone, while philosophy uses the demonstrative method for the deepest understanding.

The Nature of God

God's Existence

In his book The Exposition of the Methods of Proof, Averroes discussed how to prove God's existence. He believed there were two strong arguments for God's existence that fit with the Quran:

- The argument from "providence": This looks at how the world seems perfectly designed to support human life. Things like the sun, moon, rivers, and our place on Earth suggest a creator who made them for humans.

- The argument from "invention": This says that things in the world, like animals and plants, seem to have been invented. This means there must be a designer behind their creation, and that designer is God.

God's Qualities

Averroes believed in the idea of one God (tawhid). He argued that God has seven main qualities: knowledge, life, power, will, hearing, vision, and speech. He explained that God's knowledge is different from human knowledge. God knows the universe because He created it, while humans learn about the universe by observing it.

The World's Beginning

For centuries before Averroes, there was a debate among Muslim thinkers: Was the world created at a specific moment, or has it always existed? Some philosophers believed the world had always existed. But religious scholars often disagreed, saying this went against Islamic belief.

Averroes responded to these debates in his book Incoherence of the Incoherence. He argued that the differences between these views were not so great as to cause major religious disagreements. He also said that the idea of the world always existing didn't necessarily go against the Quran. He suggested that only the "form" of the universe was created in time, but its basic existence might have been eternal.

Politics and Society

Averroes shared his political ideas in his commentary on Plato's Republic. He combined Plato's ideas with Islamic traditions. He believed the best state would be one based on Islamic law (shariah). He thought that a wise ruler, like Plato's "philosopher-king," should lead the state. This ruler should love knowledge, be truthful, brave, and fair.

Averroes said that if philosophers couldn't rule directly, they should still try to guide rulers to create a good state. He believed there were two ways to teach people to be good citizens: persuasion and force. Persuasion was better, but force might be needed for those who didn't listen. He also supported war as a last resort for defense.

Like Plato, Averroes believed women should have equal roles in society, even as soldiers, philosophers, and rulers. He was sad that Muslim societies of his time limited women's public roles, saying it hurt the state.

Science and the Mind

Astronomy

Averroes criticized the old system of astronomy that said planets moved in complex circles around the Earth. He believed that planets moved in simple, perfect circles around the Earth, following Aristotle's ideas. He observed the star Canopus from Marrakesh, which was not visible from Spain. This observation helped support the idea that the Earth is round.

He knew that astronomers of his time were good at predicting planet movements using math. But he felt they didn't explain how the universe physically worked. He tried to make astronomy fit with physics, especially Aristotle's physics. He later admitted that he hadn't fully succeeded in this goal. However, his ideas influenced other astronomers.

Physics

Averroes was a "exegetical" scientist. This means he developed new ideas about nature by discussing older texts, especially Aristotle's writings. Even though he followed Aristotle closely, Averroes came up with very original theories in physics. For example, he had new ideas about the smallest parts of nature and about motion. These ideas were important for the development of physics later on. He also defined force in a way that is similar to how we define "power" in physics today.

Psychology

Averroes wrote about psychology (the study of the mind) in his commentaries on Aristotle's On the Soul. He wanted to explain the human intellect using philosophy. His ideas on this topic changed over time.

In his last and most famous commentary, he proposed the theory of "the unity of the intellect". He argued that there is only one shared intellect for all humans. This intellect is not mixed with our individual bodies. To explain how different people have different thoughts, he used a concept called fikr (or cogitatio in Latin). This is the process in our brains where we think about specific things we've experienced. This theory caused a lot of debate when Averroes's works reached Christian Europe.

Medicine

While Averroes knew a lot about medical theory, he said he didn't practice medicine much, except for himself, his family, or friends. His medical book, Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb, mostly followed the ideas of Galen, an important Greek physician. Galen's ideas were based on the "four humors" (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm), which needed to be balanced for good health.

Averroes made some original contributions. He might have been the first to realize that the retina (the back part of the eye) is what senses light, not the lens, as was commonly thought. He also described stroke as a problem in the brain caused by blocked arteries from the heart. This is much closer to our modern understanding of stroke than older ideas. He was also the first to describe the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease, even though he didn't give it a name.

Averroes's Impact

In Jewish Tradition

Maimonides, a famous Jewish scholar, was very excited about Averroes's works. He said Averroes was "extremely right." Many Jewish writers in the 1200s and 1300s used Averroes's texts a lot. They translated his works into Hebrew, helping his ideas spread among Jewish thinkers.

In Latin Tradition (Europe)

Averroes had a huge impact on the Christian West through his detailed explanations of Aristotle. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, much of the knowledge from ancient Greece, including Aristotle's writings, was lost in Europe. Averroes's commentaries, translated into Latin in the 1200s, brought Aristotle's ideas back to Europe. Because of his influence, he was often simply called "The Commentator" in Latin writings. Some even called him the "father of free thought" and "father of rationalism."

The first Latin translations of Averroes's major commentaries began around 1217. Soon, his works became popular among Christian scholars. A strong group of followers, called the Latin Averroists, emerged. Paris and Padua were important centers for this movement.

However, the Roman Catholic Church reacted against Averroism. In 1270 and 1277, the Bishop of Paris condemned many ideas that were from Aristotle or Averroes, saying they went against church teachings.

Other Catholic thinkers had mixed feelings about Averroes. Thomas Aquinas, a leading Catholic thinker, used Averroes's interpretations of Aristotle a lot. But he disagreed with Averroes on many points, like the idea that all humans share the same intellect.

The Church's condemnations and Aquinas's criticisms weakened Averroism in Europe. However, it still had followers until the 1500s, when European thought started to move away from Aristotle's ideas.

In Islamic Tradition

Averroes didn't have a big impact on Islamic philosophy until modern times. One reason was geography: he lived in Spain, far from the main centers of Islamic learning. Also, his focus on Aristotle might have seemed old-fashioned to Muslim scholars of his time, who were already exploring newer ideas.

However, in the 1800s, during a period of cultural rebirth called Al-Nahda (reawakening) in the Arabic-speaking world, Muslim thinkers began to study Averroes's works again. They saw his ideas as a way to modernize Islamic intellectual traditions.

See Also

In Spanish: Averroes para niños

In Spanish: Averroes para niños

Images for kids