Independence I culture facts for kids

The Independence I culture was a group of early people called Paleo-Eskimos. They lived in northern Greenland and parts of the Canadian Arctic. This culture existed from about 2400 BC to 1900 BC. Scientists are still discussing the exact dates when they disappeared.

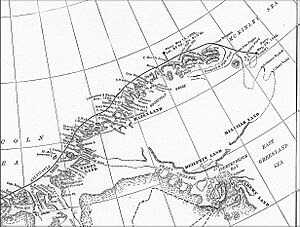

The culture is named after Independence Fjord, a long, narrow bay in Peary Land, Greenland. The Independence I people lived at the same time as the Saqqaq culture, another group of early people in southern Greenland. After Independence I disappeared, a new group called Independence II culture appeared much later, around 800 BC.

Both Independence I and Saqqaq cultures are thought to be the first known human groups in Greenland. These early people likely moved to Greenland from the Canadian Arctic. They were part of a larger group known as the Arctic Small Tool Tradition.

The Independence I people lived in a very cold and harsh environment. Their homes were designed to keep them warm. They often had a central fireplace. They also used special tools, including tiny, sharp blades called microblades. Because of the extreme cold, their main food source was the muskox.

The Independence I culture disappeared around 1900-1700 BC. The exact reasons why they left are still a mystery to scientists.

The existence of both Independence I and Independence II cultures was first discovered by a Danish explorer named Eigil Knuth. His work helped scientists learn a lot about these ancient people. Some of their biggest settlements were Pearylandville, Adam C. Knuth site, and Deltaterasserne. These places show how the Independence I people survived in the very cold High Arctic.

Who Were the Independence I People?

The Independence I culture was the earliest known human group in Northern Greenland. They lived from about 2500 BC to 1900 BC. At the same time, the Saqqaq culture lived in Southern Greenland (from 2500 BC to 800 BC). Unlike the Saqqaq, the Independence I culture lasted for a shorter time.

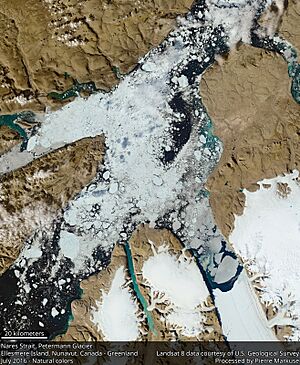

Greenland was one of the last places on Earth to be settled by humans. This was because of its remote location. People could only reach Greenland by traveling through the very cold Canadian High Arctic. They also had to cross the Nares Strait, which is a very difficult area.

Once people arrived in Greenland, they quickly spread out. Archaeologists believe the first people arrived around 2500 BC. More groups continued to migrate until about 1900 BC. They mostly settled in the northern part of Greenland, especially around Peary Land.

How Were They Discovered?

Eigil Knuth, a Danish explorer, found the Deltaterrasserne archaeological site in Peary Land. This happened in September 1948 during a research trip. At Deltaterrasserne, Knuth found signs of human life and tools. These tools were different from those used by the later Inuit people.

Knuth realized he had found a culture that lived before the Inuit. He named it "Independence culture" after the nearby Independence Fjord. Later, he divided it into Independence I and Independence II. He did this based on radiocarbon dating and differences in their stone tools. More research has since confirmed Knuth's discoveries.

Living in a Harsh Environment

Northern Greenland is a very extreme place. It has "barren deserts, permanent sea-ice cover, and months of very low temperatures and darkness." The Independence I people lived in this incredibly remote and isolated environment.

The natural world in Northern Greenland was also unstable. Environmental changes and too much hunting could make life very difficult. This might be why the Independence I culture lasted only a few centuries. In contrast, the Saqqaq culture, which arrived around the same time, lasted for almost 2000 years.

In the High Arctic, the sun stays above the horizon for two to four months each year. This is called the midnight sun. During the coldest months, the sky is lit by twilight, the aurora borealis, and the moon. The warmest month is only slightly above freezing. The coldest month has an average temperature below -30 degrees Celsius.

Their Homes

Archaeological studies show that the Independence I people could live comfortably in the High Arctic. They were nomadic, meaning they moved from place to place. So, their homes had to be light and easy to move.

Their homes were often tents, not permanent buildings. Getting firewood was difficult. Many Independence I homes had a central passage and a fireplace. One type of home was an "elliptical double platform dwelling." This home had a stone-built passage in the middle with a box-shaped fireplace. Eigil Knuth thought these were winter homes. He believed they might have used muskox hides to cover the floor.

Another type of home was found at the Adam C. Knuth site. This home had a central fireplace with four sides. Three sides had platforms for living, and the fourth side was an entrance. The home was divided into three areas: living spaces on each side, the central passage, and the fireplace.

The only heat in these tents came from the fireplace. Scientists have not found any evidence that they used oil or blubber lamps. Some fireplaces were built in the middle of a tent ring. Others were box-shaped hearths, about 40 cm by 40 cm, made of stone slabs.

Daily Life and Food

The Independence I culture were hunter-gatherers. This means they hunted animals and gathered plants for food. At the Deltaterrasserne site, scientists found muskox and fish bones. This shows they used the animals and fish from the land and water for survival.

Their diet varied slightly depending on where they lived. At the Adam C. Knuth site, their diet included Arctic fox (45.1%), muskox (31.6%), Arctic hare (4.4%), ringed seal (1.3%), brent goose (2.2%), rock ptarmigan (7.7%), and Arctic char (4.4%). The large amount of arctic fox was unusual. However, muskox was their main food source, which was typical for Independence I.

Muskox were very important to the Independence I people. They used every part of the animal: meat, fat, and bone marrow for food. They used long bones for tools and thick fur for clothing and warmth. So, muskox provided them with food, clothing, tools, and warmth.

No clothing has been found from Independence I sites. However, scientists believe they made finely stitched clothes from animal skins. Broken bone needles found at their sites suggest they sewed their garments.

Their Tools

Only a few Independence I sites have preserved organic matter (like wood or bone). However, some tools have been found. A few harpoon heads were found at Canadian Independence I sites, but none in Greenland.

The tools used by Independence I people were quite unique. They preferred materials like chert and other stone types. These included black basalt, agate, and black, blue, and gray chert. Their tool kit included end and side scrapers and large knife blades. Another special tool was a coarsely made adze head with ground edges, made from basalt. This helped tell them apart from the Saqqaq culture.

Tiny, sharp blades called microblades make up a large part of the tools found. These were narrow, glass-like slivers of flint with long, straight edges. They were made using very special techniques. When Eigil Knuth found these tiny, razor-edged microblades, they looked nothing like traditional Inuit tools. This helped him realize he had discovered a culture that lived before the Inuit.

Important Discoveries

Over 60 years, Eigil Knuth found over 51 Independence I sites. However, only a few of these sites show signs of people living there for a long time. Most were likely used for only a few seasons. The most important sites are Pearylandville, Adam C. Knuth site, and Deltaterasserne. The small number of major sites might mean they often moved to new hunting grounds.

Key Sites

Pearylandville

Pearylandville is the largest Paleo-Eskimo site in Peary Land. It was discovered by Eigil Knuth. The animal remains found there are mostly muskox. There are also arctic fox, hare, arctic char, geese, and gulls. The ruins contain many stone tool fragments and animal bones. This suggests they were used as winter homes for several months. However, most ruins have fewer than 100 tools. This means they were probably used for shorter periods.

It is hard for researchers to know exactly how long this site was used. It is difficult to tell old remains from new ones. Some scientists think Pearylandville might have been a gathering place for Independence I people. Knuth led major digs here in the 1960s. He found 820 stone tools, 5312 flakes, and 2274 animal bones.

Adam C. Knuth Site

Adam C. Knuth is a large open site with many ruins. These include homes and places where stone tools were made. Knuth found this site by accident in 1980. It was covered in stone fragments and tools. It is the second largest site after Pearylandville.

The site has 14 ruins, including well-built mid-passage homes and 10 stone storage areas. Some of the homes were larger and more strongly built. Scientists believe these were used as winter homes. Lighter tent rings found there were likely used in the summer. The way tools were spread out in the homes suggests that different areas might have been used by men and women.

Deltaterasserne

Deltaterasserne is another large site discovered by Eigil Knuth. The tools and ruins found here helped Knuth discover both Independence I and Independence II cultures. The site has several home ruins and outdoor fireplaces. This suggests it was used in autumn and winter.

The larger homes at this site suggest they were main settlements during the dark winter. During winter, the Independence I people likely relied on stored food. However, other researchers think Deltaterasserne might have been a summer site. This is because they found many bird bones there. This site is linked to Pearylandville because the microblade ruins at both sites are the same. This suggests the same people likely lived at both places. This site shows signs of both Independence I and Independence II cultures, but the Independence I settlement was more intense.

Why Did They Disappear?

The Independence I culture lived in Greenland for about 500–700 years. The Independence II culture appeared roughly 600 years after Independence I disappeared. The very cold temperatures of northern Greenland might have played a role in their disappearance. Also, their main food source, the muskox, could be overhunted. This unreliability of food might have led to their decline.

See also

In Spanish: Cultura Independencia I para niños

In Spanish: Cultura Independencia I para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |