Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Isle de Jean Charles

|

|

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Terrebonne |

| Elevation | 2 ft (0.6 m) |

| Population

(2019)

|

|

| • Total | 26 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 985 |

Isle de Jean Charles (called Isle à Jean Charles by locals in Louisiana French) is a thin strip of land in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. For over 170 years, it has been the historic home and burial ground for the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians.

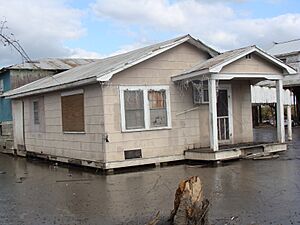

The people living on the island have faced a big threat. Louisiana's coast is losing land very quickly. It loses an area the size of Manhattan every year! In 1955, Isle de Jean Charles was over 22,000 acres. Now, about 98% of its land is gone. This is because saltwater is coming in and the ground is sinking. In January 2016, the state of Louisiana received money to help the community move to a new, safer place.

Contents

Island History and Land Loss

In the 1830s, the ancestors of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe moved to Isle de Jean Charles. They were escaping the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears. By 1910, the island had grown to 77 families. The people on the island made a living by fishing, oyster farming, trapping, and farming.

Until 1953, the only way to get to the mainland was by boat. Then, a road was built. But this road often flooded and wore away because it went through open water. In the 1940s, companies started drilling for oil and digging near the island. These activities made the island and its road erode even faster.

Why the Land is Disappearing

Isle de Jean Charles used to be over 5 miles wide and 11 miles long. Today, it is only about 1/4 mile wide and 2 miles long. Both nature and human activities have caused this land loss.

- Natural Causes:

- Hurricanes, like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, flooded the area with saltwater. This damaged homes and made the land sink.

- Rising sea levels also contribute to land loss. Climate change has made sea levels rise faster in the last century. This speeds up erosion for coastal islands like Isle de Jean Charles.

- Human-Made Causes:

- Dams and levees, built by people, have changed how water flows.

- Dredging canals for shipping and oil pipelines has also worn away the marshland.

- Fracking (a way to get oil and gas) makes the land sink. This happens because taking materials from underground removes support for the land above.

- Levees also cause pollution around the area. This harms the many different plants and animals living there.

These changes have reduced the number of plants and animals in the marshland. This has made life harder for the tribe. Many tribal members who could afford to move have already left the island. This has made it harder for them to keep their customs and traditions alive.

The Army Corps of Engineers did not include Isle de Jean Charles in their levee projects. This was partly because it would cost an extra $100 million. This made the island even more open to natural disasters. By the early 2000s, only 25 families were left. The tribe's Chief, Albert Naquin, worked hard to move the whole community. He wanted to save their culture and traditions. In 2016, after more than ten years, the tribe finally had a partial success. The move of people from Isle de Jean Charles is the first time a whole community has moved in Louisiana because of climate change.

In 2013, an award-winning documentary called Can't Stop The Water was filmed about the community's struggles.

Community Resettlement Efforts

The Isle de Jean Charles Tribal Council decided they needed help to move their community. This was because the government was not helping enough with flood protection and land repair. Chief Albert Naquin and the Tribal Council have worked for 16 years to move their community to higher, safer ground. They have made good progress, but there have also been many delays.

In 2002, the US Army Corps of Engineers worked with the tribe to find a new place to live. The idea was to keep the community together. However, most people from Isle de Jean Charles did not want to move. Their culture was very connected to their land. Some residents felt the government wanted them to move so oil companies could use the area freely. The tribe had ongoing conflicts with oil and gas companies over land.

The US Army Corps of Engineers said they would give funding if the community found a suitable property. But the Louisiana government did not think about the social, mental, and money problems that moving would cause for fishing families. The tribe would lose their local knowledge and face a lot of stress fighting for their land and way of life.

Since 2010, the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe has worked with partners and experts. They have developed their own plan for moving. On January 25, 2016, the State of Louisiana received $48 million. This money was from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It was given to help with the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement.

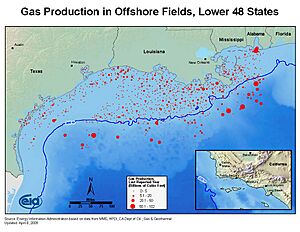

Oil and Gas in Terrebonne Parish

Terrebonne Parish in Louisiana has a lot of oil and gas production. Oil and gas companies have a big influence on the coastal communities here. About 90% of the land in Terrebonne Parish belongs to large manufacturing companies. Isle de Jean Charles is located near many oil fields that are still in use. Building oil rigs and pipelines continues to change the land in the wetlands.

Discovery and Production

In the late 1920s, the Texaco oil company started looking for oil in Louisiana's bayous and marshlands. Oil was first found in Terrebonne Parish in 1929. Texaco and other groups quickly took control of the land.

Oil and natural gas production grew very fast in Terrebonne Parish. It reached its highest levels in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1977, they produced over 31 million barrels of oil and 550 billion cubic feet of gas. The OPEC Embargo of 1973 and 1974 made domestic oil production very important. Since the late 1970s, oil and gas production has slowly decreased.

Environmental Impact

To help move oil and natural gas, the Houma Navigation Canal was built. This man-made waterway connected Houma, the largest city in Terrebonne Parish, to the Gulf of Mexico. It was finished in 1962. This canal is believed to have directly harmed the wetlands of southern Louisiana.

Higher levels of salt in the water from the nearby bay have caused problems. Also, more man-made waterways, pipelines, and smaller canals have made the wetlands worse. This is especially true east of the Houma Navigation Canal, where Isle de Jean Charles is located.

Education

The community is part of the Terrebonne Parish School District.

Also, the public school École Pointe-au-Chien gives special admission to children living in Isle de Jean Charles.

In Popular Culture

- Director Benh Zeitlin said that Isle de Jean Charles was the inspiration for "The Bathtub." This was the fictional island in his 2012 film, Beasts of the Southern Wild.

- Cottage Films made a documentary called Can't Stop The Water (2013). It was directed by Rebecca and Jason Ferris and filmed tribal life on Isle de Jean Charles for years.