Alfred Ewing facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

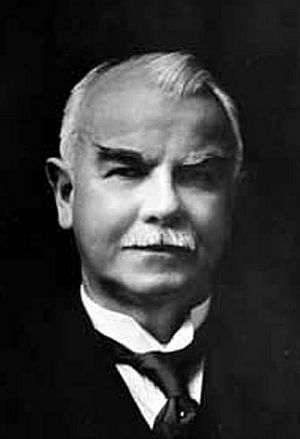

Sir Alfred Ewing

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 27 March 1855 Dundee, Scotland

|

| Died | 7 January 1935 (aged 79) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Known for | hysteresis |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1895) Albert Medal (1929) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | physics and engineering |

| Institutions | University of Edinburgh |

Sir James Alfred Ewing (March 27, 1855 – January 7, 1935) was a Scottish physicist and engineer. He is most famous for his work on how metals behave magnetically. He also discovered and named the term hysteresis. Hysteresis describes how a system's output depends not just on its current input, but also on its past inputs.

Ewing was known for being very careful about his appearance. He was seen as brilliant and successful. He also cared about his position in society. When he was chosen to lead a new code-breaking group, a naval director said he was "too distinguished" to be under others' direct orders. His first wife, Annie, was related to George Washington.

Contents

Sir Alfred Ewing: A Life of Discovery

Early Life and Education

Ewing was born in Dundee, Scotland. He was the third son of a minister. From a young age, he loved science and technology. He spent his pocket money on tools and chemicals. He even used his family's attic for experiments, which sometimes caused "hair-raising explosions."

He won a scholarship to the University of Edinburgh. There, he studied physics and later graduated in engineering. During his summer breaks, he helped lay telegraph cables. This work took him to places like Brazil.

Pioneering Work in Japan

In 1878, Ewing moved to Meiji Era Japan. He was one of the o-yatoi gaikokujin, which means "hired foreigners." These experts helped Japan modernize. He became a professor of mechanical engineering at the Tokyo Imperial University. He played a key role in starting the study of seismology (the science of earthquakes) in Japan.

In Tokyo, Ewing taught about machines, engines, electricity, and magnetism. He did a lot of research on magnetism. This is where he first used the word 'hysteresis'. He also worked on earthquakes. He helped develop the first modern seismograph (a device that measures earthquakes). He worked with T. Lomar Gray and John Milne on this project.

Ewing, Gray, and Milne also started the Seismological Society of Japan in 1880. This society helped advance the study of earthquakes.

Improving Life in Dundee

In 1883, Ewing returned to his hometown of Dundee. He became the first Professor of Engineering at University College Dundee. He was shocked by the poor living conditions in some parts of the town. He felt they were worse than in Japan.

He worked hard with local leaders and businesses to make things better. He focused on improving sewer systems. He also aimed to lower the number of babies who died young. Today, the Ewing Building at the University of Dundee is named after him. It houses the School of Engineering, Physics, and Mathematics.

Research at Cambridge

In 1890, Ewing became a professor at the University of Cambridge. He continued his research into how metals become magnetized. He found that magnetizing a metal lagged behind the electric current applied to it. He drew the special "hysteresis curve" to show this. He thought that tiny parts inside the metal acted like small magnets.

Ewing also studied the structure of metals. In 1903, he was the first to suggest that metal parts break down due to tiny flaws. These flaws are called slip bands. In 1895, he received a special award for his work on magnetism.

He was good friends with Sir Charles Algernon Parsons. They worked together on developing the steam turbine. Ewing also wrote a book called The Steam Engine and other Heat Engines. In 1897, he helped test the experimental ship Turbinia. This ship set a new speed record of 35 knots (about 65 km/h).

In 1898, Ewing became a Professor at King's College, Cambridge.

Service to the Admiralty

In 1903, Ewing was chosen to be the first Director of Naval Education (DNE) for the British Navy. He was honored for his work, becoming a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1906. He was then made a Knight Commander of the Bath in 1911.

During World War I, from 1914 to 1917, Ewing led "Room 40". This was the British Navy's secret intelligence group. Their main job was to decode German naval messages. Room 40 became very famous when they decoded the Zimmermann Telegram in 1917. This message suggested that Germany wanted to help Mexico get back parts of the southwestern United States. Publishing this telegram helped bring the United States into World War I.

Ewing's first wife, Annie, passed away in 1909. In 1912, he married Ellen. She was the daughter of his old friend, John Hopkinson. Ewing had two children with his first wife.

Leading the University of Edinburgh

In 1916, Ewing became the Principal of the University of Edinburgh. He made many important changes and improvements there. He stayed in this role until he retired in 1929. In 1927, he gave a lecture where he first publicly spoke about the secret work done by Room 40. A building at the university is named after him.

Sir Alfred Ewing passed away in 1935. He is buried in Cambridge with his second wife, Lady Ellen Ewing.

Honours

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1878)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1887)

- LL.D. (honorary degree), University of Edinburgh (1902)

- John Scott Medal (1907)

- CB (1907)

- KCB (1911)

- President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1924–1929)

- Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts (1929)

- President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1932)

- The James Alfred Ewing Medal has been awarded since 1938 for important contributions to engineering research.

Works

- 1877: (with Fleeming Jenkin) On Friction between Surfaces moving at Low Speeds

- 1883: A Treatise on Earthquake Measurement

- 1899: Strength of Materials

- 1900: Magnetic Induction in Iron and Other Metals, 3rd edition

- 1910: The Steam Engine and Other Engines, 3rd edition

- 1911: Examples in Mathematics, Mechanics, Navigation and Nautical Astronomy, Heat and Steam, Electricity, for the use of Junior Officers Afloat

- 1920: Thermodynamics for Engineers

- 1921: The Mechanical Production of Cold, second edition

- 1933: An Engineer's Outlook

See Also

In Spanish: Alfred Ewing para niños

In Spanish: Alfred Ewing para niños

- Anglo-Japanese relations

- Room 40