Fleeming Jenkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fleeming Jenkin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 25 March 1833 |

| Died | 12 June 1885 (aged 52) Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for | Telpherage |

| Scientific career | |

| Influenced | Charles Frewen Jenkin |

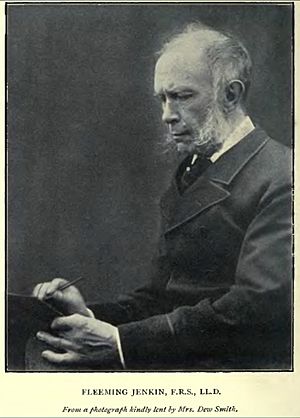

Henry Charles Fleeming Jenkin (born March 25, 1833 – died June 12, 1885) was a brilliant engineer and inventor from Scotland. He was a professor of engineering at the University of Edinburgh. He was known for many things, including inventing the "telpherage" system, which was an early type of cable car.

Fleeming Jenkin was a very talented person. Besides being an engineer, he was also an expert in electricity, an economist, a teacher, and even an artist and actor!

Contents

Early Life and Education

Fleeming Jenkin was born in Dungeness, England. His father was a captain in the coast guard. His mother, Henrietta Camilla Jenkin, was a writer and taught him a lot at home.

As a child, he moved around a lot with his family. He lived in Scotland, where he went to school at Jedburgh and the Edinburgh Academy. There, he was classmates with famous scientists like James Clerk Maxwell.

His family later moved to Frankfurt, Germany, and then Paris, France. In Paris, he saw the Revolution of 1848 happen. He then moved to Genoa, Italy, where he studied at the University of Genoa. He was the first Protestant student there. He earned a degree with top honors, focusing on electromagnetism. He also loved art and won a silver medal for drawing.

Becoming an Engineer

In 1850, Jenkin worked in a locomotive shop in Genoa. Then, his family moved back to England. In 1851, he started training as a mechanical engineer at the works of William Fairbairn in Manchester. It was hard work, but he enjoyed it.

He continued his studies at home, reading about engineering and mathematics. He also loved literature and poetry. He visited the home of Alfred Austin, a kind and cultured lawyer. There, he met Annie Austin, who would later become his wife.

In 1856, he worked as a draughtsman at Penn's engineering works. He then joined Messrs. Liddell and Gordon, who worked on new submarine telegraph cables. This was a very exciting new field, and Jenkin was thrilled to be part of it.

Working with Submarine Cables

First Cable-Laying Voyages

In 1857, Jenkin became an engineer for R.S. Newall and Company. This company helped make the first Atlantic cable. He designed and set up machines for ships that laid cables. He wrote to his fiancée, "My profession gives me all the excitement and interest I ever hope for."

In 1855, he helped prepare the ship S.S. Elba for a trip to recover a lost telegraph cable in the Mediterranean Sea. Other attempts to lay this cable had failed because of deep water and tangled wires. Jenkin designed new equipment for the ship to help pick up the cable.

He wrote letters about his experiences during this trip. He saw how dangerous the work could be when a shipmate was badly injured. He realized how much he disliked seeing pain.

Meeting William Thomson

In 1859, Jenkin met William Thomson (who later became Lord Kelvin), a very famous scientist. Thomson was impressed by Jenkin's intelligence and honesty. They talked a lot about electricity and telegraphs. This meeting led to a lifelong friendship and partnership.

Soon after, Jenkin married Annie Austin. He loved his wife very much, writing that he was "desperately in love" with her even after many years of marriage.

Later that summer, he went on another trip to lay a cable from the Greek islands of Syros and Crete to Egypt.

Life as a Professor and Inventor

New Partnerships and Family Life

In 1861, Jenkin started his own engineering partnership with H. C. Forde. Business was slow at first, which was worrying because he had a young family. He and Annie had their first son in 1863 and moved to a cottage in Claygate.

Despite financial worries, Jenkin stayed positive. He believed he would succeed. He enjoyed gardening and writing reviews. Famous scientist James Clerk Maxwell sometimes visited him.

In 1865, his second son was born. Jenkin became ill with rheumatism after caring for his wife. This illness bothered him for the rest of his life.

Professor at Universities

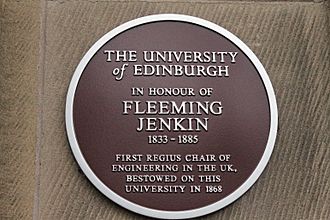

In 1866, Jenkin became a professor of engineering at University College London. Two years later, he was chosen to be the new Regius Professor of Engineering at University of Edinburgh. He was very happy about this, as it meant he could focus on studying in winter and practical work in summer.

In June 1869, he was on board the huge ship Great Eastern when it laid the French Atlantic cable from France to Saint-Pierre. He worked with other famous engineers like Sir William Thomson.

Working with Thomson and Varley

Jenkin's new job in Edinburgh led to a partnership in cable work with Thomson and C. F. Varley. Jenkin's practical skills helped Thomson, allowing Thomson more time for other research. In 1870, they profited from the "siphon recorder," an invention by Thomson that helped send messages over long cables.

In 1873, Thomson and Jenkin worked on the Western and Brazilian cable system. This connected Brazil to the West Indies and Argentina.

Ideas in Economics and Public Health

In 1870, Jenkin wrote an important essay about "supply and demand" in economics. He was one of the first to use diagrams to show how these ideas work. This method is still used today and was made popular by economist Alfred Marshall.

In 1878, Jenkin also helped public health with his pamphlet Healthy Houses. He suggested that groups of experts could inspect homes to make sure they were safe and clean. This idea became popular in many cities.

Personality and Achievements

Jenkin was a clear and good speaker, and a successful teacher. He was known for being very honest and thorough in his work. He made important measurements of electrical properties in submarine cables. He also helped create standard units for electrical measurements.

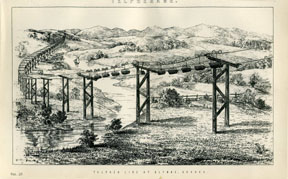

His most important invention was "telpherage." This was a system to transport goods and people using electric carriers on a wire. He patented it in 1882. He spent his last years working on this project, hoping it would be a great success. The first public telpher line opened in Glynde, England, shortly after he died.

Jenkin also had many other talents. He could quickly draw portraits. He wrote papers on many different topics, from ancient philosophy to the sounds of speech. He even built a phonograph (an early record player) just from reading newspaper reports about it!

He loved to read and enjoyed authors like Shakespeare and Charles Dickens. He was a fast and fluent talker. He was known for being very direct. He once said, "We are not here to be happy, but to be good."

Although some people found him a bit rough, his close friends and family loved him. He was a good father, joining in his children's games and helping them with their studies. He also loved animals, and his dog, Plate, often went with him to the university.

Jenkin enjoyed outdoor activities like shooting, riding, and swimming. He loved the Scottish Highlands and even tried to learn Scottish Gaelic.

Views on Evolution

In 1867, Fleeming Jenkin wrote a review of Darwin's book On the Origin of Species. Jenkin questioned Darwin's idea of natural selection. At the time, many scientists believed in "blending inheritance," meaning that traits from parents would simply mix together in their children.

Jenkin argued that if blending inheritance was true, any new helpful changes (mutations) would quickly get diluted and disappear over a few generations. This would make it hard for natural selection to work over long periods.

Darwin found Jenkin's arguments challenging. Although Jenkin's argument had a small mistake, it still made Darwin think more deeply about how traits were passed down.

Selected Works of Fleeming Jenkin

- 1868: The Atomic Theory of Lucretius, North British Review, link from Wikisource.

- 1870. "The Graphical Representation of the Laws of Supply and Demand, and their Application to Labour," in Alexander Grant, ed., Recess Studies, ch. VI, pp. 151–85. Edinburgh. Scroll to chapter link.

- 1873: Electricity and Magnetism (first edition), link from HathiTrust.

- 1873 (editor) Reports of the Committee on Electrical Standards appointed by the British Association for the Advancement of Science link from HathiTrust.

- 1887: Sydney Colvin & James Alfred Ewing editors, Papers, Literary, Scientific, &c, volume 1, preview from Google Books.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |