Room 40 facts for kids

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (meaning "old building"), was a top-secret group in the British Admiralty during World War I. Their main job was cryptanalysis, which means breaking secret codes and ciphers.

This special group started in October 1914. It began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, who led Naval Intelligence, gave some intercepted German radio messages to Alfred Ewing. Ewing was the Director of Naval Education and enjoyed solving ciphers as a hobby. He brought in talented civilians like William Montgomery, a German translator, and Nigel de Grey, a publisher.

During the war, Room 40 was incredibly busy. They managed to decode about 15,000 secret German messages. These messages came from both wireless radio and telegraph lines. Their most famous success was decoding the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917. This secret message from Germany suggested an alliance with Mexico against the United States. Decoding it was a huge win for Britain. It played a big part in convincing the neutral United States to join the war on the Allied side.

Room 40's work got a big boost from captured German codebooks and maps. Britain's allies, the Russians, found these items from the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg. The Magdeburg ran aground off Estonia in August 1914. The Russians found three copies of the German naval codebook, called the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM). They kept two and gave one to the British. Later, in October 1914, the British also got the Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB) codebook. This was used by German warships, merchant ships, zeppelins, and U-boats. It was taken from an Australian-German ship called Hobart. Then, in November, a British trawler found a safe from a sunken German destroyer. Inside was the Verkehrsbuch (VB) code. This code was used for messages between German naval officers and embassies.

Even though Room 40 grew and moved to other offices, its original name stuck. Alfred Ewing led the group until May 1917. Then, Admiral Hall took over. Room 40 decoded German messages throughout the war. However, there was a rule that only naval experts could analyze the decoded information. This meant the code breakers themselves weren't allowed to understand or interpret the messages they had just solved.

Contents

How Britain Started Breaking Codes

Before World War I, Britain decided that if war broke out with Germany, they would cut Germany's underwater communication cables. In August 1914, British ships cut Germany's five transatlantic cables. They also cut six cables between Britain and Germany. This meant Germany had to send many more messages by wireless radio. These radio messages could be intercepted, but they were secret and coded.

At the start of the war, Britain didn't have any groups set up to break codes. The navy had only one radio station to listen for messages. But other groups, like the Post Office and the Marconi Company, also started recording German messages.

The First Code Breakers

Intercepted messages began arriving at the Admiralty, but no one knew what to do with them. Henry Oliver, who was in charge of naval intelligence, was very busy with the war. He didn't have anyone with code-breaking experience. So, he asked his friend Sir Alfred Ewing for help. Ewing was the Director of Naval Education and knew about radio and ciphers.

Ewing was asked to create a group to decode messages. He first recruited teachers from naval colleges. These included Alastair Denniston, who taught German. Denniston later became second-in-charge of Room 40. After the war, he became the head of the Government Code and Cypher School, which was at Bletchley Park during World War II.

Other early recruits included Charles Godfrey, a headmaster, and Professor Henderson, a scientist. None of them knew how to break codes at first. They were chosen because they knew German and could keep secrets. They worked in Ewing's office, sometimes hiding when visitors arrived.

Cracking German Codes

A similar code-breaking group started in the army, called MI1b. They tried to work with the navy's group. But they didn't have much success until the French shared some German military ciphers. The two groups worked separately on messages about the Western Front.

Some volunteers also helped by intercepting German messages from a coastguard station in Norfolk. This station, along with the one in Stockton, became key parts of the 'Y' service. This service grew quickly and could intercept almost all official German messages.

The Magdeburg Codebook

The first big breakthrough for Room 40 came from the German light cruiser SMS Magdeburg. In August 1914, the Magdeburg ran aground off Estonia. Russian ships approached and opened fire. The German crew tried to destroy their secret papers, but they couldn't. The commander and 57 crew members were captured.

The Russians found a copy of the German naval codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), on the Magdeburg. They kept two copies and gave one to the British. This codebook was very important.

At first, the code breakers couldn't understand the messages, even with the SKM. They realized the messages were also enciphered (scrambled) after being coded. A German expert, C. J. E. Rotter, figured out how to break this extra layer of scrambling. He found that messages from one German transmitter were numbered in order, which helped him crack the cipher.

The decoded messages showed where Allied ships were. This information was useful. Soon, Room 40 realized that similar coded messages were being sent on short-wave radio. They started listening to these, and it gave them valuable information about the movements of the German High Seas Fleet.

The SKM codebook was very large and hard to change. It had 34,300 different instructions. It was used by the German fleet for important actions until mid-1916. Even when a new codebook was introduced, some German ships didn't want to use it because it was too complicated. The Germans knew the Magdeburg's codebook might have been captured. But they relied on the extra scrambling to keep messages secret. However, the key for this scrambling wasn't changed often enough.

The HVB Codebook

Another important codebook, the Handelsverkehrsbuch (HVB), was captured in Australia. In August 1914, the German-Australian ship Hobart was seized near Melbourne. The ship's captain tried to get rid of secret papers, but he was caught. The HVB codebook was found. This code was used by the German navy to talk to its merchant ships and within the High Seas Fleet. A copy reached the Admiralty in London by the end of October.

The HVB code had 450,000 possible four-letter groups. It was used for routine messages and by U-boats. The Germans knew by November 1914 that the HVB code was compromised. But they didn't replace it until 1916.

In 1916, the HVB was replaced by the Allgemeinefunkspruchbuch (AFB). The British quickly understood this new code from test signals. The AFB was used even more widely, including by German allies like Turkey and Bulgaria.

The VB Codebook

A third codebook, the Verkehrsbuch (VB), was found after the German destroyer SMS S119 was sunk in October 1914. During a battle, the commander of S119 threw all secret papers overboard in a lead-lined chest. Everyone thought the papers were destroyed. But on November 30, a British trawler found the chest. It contained the VB codebook, which was used by senior German naval officers. Room 40 called this "the miraculous draft of fishes."

The VB code had 100,000 groups of 5-digit numbers. It was meant for messages sent overseas to warships and embassies. It was very important because it gave Room 40 access to communications between German naval officers in different countries.

In 1917, naval officers switched to a new key for the VB code, but Room 40 quickly broke that too. The VB code continued to be used for other purposes throughout the war.

Room 40's Operations

In November 1914, Captain William Hall became the new head of Naval Intelligence. He had to stop his sea duties due to illness, but he proved to be very successful in this new role.

The code-breaking group became more official and moved to Room 40 in the Admiralty Old Building on November 6, 1914. This is how it got its famous name. Room 40 is still there today, on the first floor of the original building in Whitehall, London. It was on the same hallway as the Admiralty boardroom. Only a few top officials, like the First Sea Lord Sir John Fisher and Winston Churchill (who was First Lord at the time), were allowed to know about Room 40.

All decoded messages were kept completely secret. Only the Chief of Staff and the Director of Intelligence received copies. Commander Herbert Hope was chosen to review and interpret the messages. Hope didn't know about code breaking or German, but he understood naval procedures very well. He worked with the code breakers and translators to make sense of the messages.

As more messages were intercepted, Hope decided which ones were important. The German fleet often reported their ship positions by radio. Room 40 could build a clear picture of the German fleet's movements. They could even guess where German minefields were. If the Germans changed their normal patterns, it meant an operation was about to happen, and a warning could be given. Room 40 also had detailed information about submarine movements. Most of this information was kept secret within Room 40.

Admiral Jellicoe, who commanded the Grand Fleet, asked for copies of the codebooks. He wanted to use them to intercept German signals himself. But very little information from Room 40 reached him, and it was often slow. This was because the Admiralty wanted to keep Britain's ability to read German messages a complete secret.

Tracking Ships with Radio

In early 1915, British and German forces started using radio direction-finding equipment. This equipment could figure out where a radio signal was coming from. Captain Round of the Marconi Company built a system for the navy. By May 1915, the Admiralty could track German submarines crossing the North Sea.

Room 40 had very accurate information about German ship positions. The Germans knew Britain used direction-finding radio. This sometimes helped cover up the fact that Britain was actually reading their messages. Room 40 found that British direction-finding systems were more accurate than German ones.

Room 40's priority was to keep their knowledge secret. Admiral Jellicoe was the only one who received accurate maps of German minefields, which were made from Room 40's information. Other commanders received some information, but Jellicoe was not happy with how little they got.

British ships were told to use radio as little as possible and with low power. Room 40 benefited greatly from the Germans' habit of talking freely on the radio and using full power. This made German messages easy to intercept and analyze. The German fleet didn't try to limit its radio use until 1917. Even then, it was because they thought Britain was using direction finding, not because they believed their messages were being decoded.

The Zimmermann Telegram

Room 40 played a key role in several naval battles. They detected major German movements into the North Sea, leading to the Battle of Dogger Bank in 1915 and the Battle of Jutland in 1916. This allowed the British fleet to intercept the Germans.

But Room 40's most famous success was decoding the Zimmermann Telegram. This was a secret message from the German Foreign Office in January 1917. It was sent through Washington to the German ambassador in Mexico. Many people call it the most important intelligence win for Britain in World War I. It was one of the first times that secret intelligence changed world events.

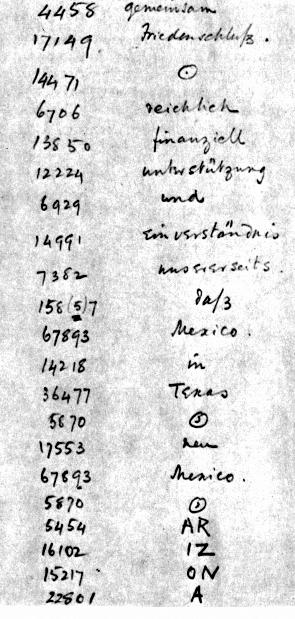

In the telegram, Nigel de Grey and William Montgomery learned that German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann offered Mexico parts of the United States. These included Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. This was an offer to get Mexico to join the war as a German ally.

Captain Hall passed the telegram to the U.S. A plan was made to hide how Britain got the message. The United States then made the telegram public. On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, joining the Allies.

Key People in Room 40

Some of the other important people who worked in Room 40 included Frank Adcock, John Beazley, Francis Birch, Walter Horace Bruford, William 'Nobby' Clarke, Frank Cyril Tiarks and Dilly Knox.

Room 40 Becomes GC&CS

In 1919, Room 40 was closed down. Its work was combined with the British Army's intelligence unit, MI1b. Together, they formed the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS). This new group later moved to Bletchley Park during World War II. After that, it was renamed Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and moved to Cheltenham.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |