Johann Friedrich Böttger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Johann Friedrich Böttger

|

|

|---|---|

Johann Friedrich Böttger.

|

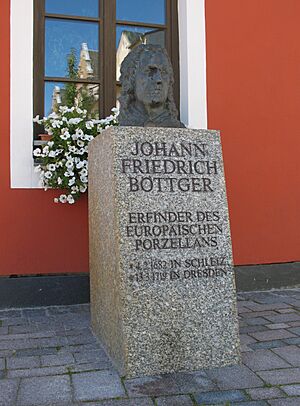

Johann Friedrich Böttger (also spelled Böttcher or Böttiger) was a German alchemist. He was born in Schleiz on February 4, 1682, and passed away in Dresden on March 13, 1719. Böttger is widely known for being the first European to figure out how to make hard-paste porcelain. This important discovery happened in 1708.

The Meissen factory, which started in 1710, was the first place in Europe to make porcelain in large amounts. Böttger kept the porcelain recipe a secret for his company. This meant other people across Europe had to keep trying to discover the secret on their own.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and the Search for Gold

Johann Friedrich Böttger was born in Schleiz in 1682. His father worked at the mint. In 1682, his family moved to Magdeburg. Sadly, his father died that same year. In 1685, his mother married Johann Friedrich Tiemann. He was a town major and engineer. Tiemann helped Böttger get a good education.

Around 1700, when Böttger was 18, he worked as a chemist's helper in Berlin. He was also an alchemist. Alchemists tried to find the philosopher's stone. This was a secret substance. People believed it could cure any sickness. They also thought it could turn regular metals into gold.

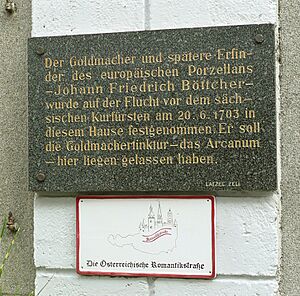

Böttger worked in secret to find this "gold-making tincture." Soon, people heard about his work. King Frederick I of Prussia was very interested in gold. He heard about Böttger and wanted him to be taken into protection. Böttger tried to escape, but he was caught. He was then taken to Dresden.

Working for the King

The ruler of Saxony, Augustus II of Poland (also known as Augustus the Strong), was always short on money. He also wanted gold. He demanded that Böttger make the "gold-making tincture." Böttger was kept in a dungeon. He spent many years trying to make the gold. He hoped this would earn him his freedom.

By 1704, the king was impatient. He ordered a scientist named Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus to watch over Böttger. At first, Böttger did not want to help von Tschirnhaus with his own experiments. But Böttger had no success himself. He began to fear for his life.

By September 1707, Böttger slowly started to work with von Tschirnhaus. Böttger did not want to work on porcelain. He thought it was von Tschirnhaus's project. But the king ordered him to do it. Böttger likely realized that discovering porcelain was his best chance. It was the next best thing to gold. It could satisfy the king and save him.

The Discovery of Porcelain

In December 1707, the king visited a new lab. It was set up for von Tschirnhaus in Dresden. The king wanted to see their progress. Under von Tschirnhaus's guidance, experiments continued. Miners and metal workers from Freiberg also helped. They tried different types of clay.

They made great progress in 1708. They found two good minerals. One was a very fine, pure white clay called kaolin from Schneeberg. The other was alabaster, which helped the mixture melt. After many years, they found two more key ingredients. These were China Stone and Quartz. When all these were mixed and heated to at least 1300 degrees Celsius, they finally got the desired result: porcelain.

August the Strong made von Tschirnhaus a director of a new factory. But von Tschirnhaus died suddenly on October 11, 1708. This stopped the project for a while.

The Porcelain Secret

Porcelain was first made in China around 200 BC. A thousand years later, China made clear, see-through porcelain. Chinese porcelain came to Europe through trade. Everyone admired it, but no one knew how it was made. Porcelain was as valuable as silver and gold. People even called it "white gold."

On March 20, 1709, Melchior Steinbrück arrived in Dresden. He was von Tschirnhaus's family tutor. He took charge of von Tschirnhaus's belongings. He also got hold of the porcelain recipe. On March 28, 1709, Böttger told the king about the invention of porcelain. Böttger became the head of Europe's first porcelain factory. Their discovery of porcelain changed the future of the West forever.

Later, in 1719, a person named Samuel Stölzel escaped from Meissen. He shared the secret of making porcelain in Vienna. He said that von Tschirnhaus, not Böttger, had discovered porcelain. Also in 1719, a factory secretary named Caspar Bussius reported the same thing. He said Böttger got the written "science" from Steinbrück.

In a report from 1731, Peter Mohrenthal wrote about it. He said that von Tschirnhaus was the first to find the secret. He also said Böttger later worked out the details. He added that von Tschirnhaus's death stopped his work.

Böttger Ware

In the late 1600s, Chinese Yixing clay teapots came to Europe. These teapots were made from special clay. They were popular in China because the unglazed stoneware was thought to make tea taste better. Europeans wanted to copy this new material.

Böttger was in touch with some Dutch potters who made similar red stoneware. He developed his own "Böttger ware." This was a dark red stoneware. It was first sold in 1710. Other people also made and copied it until about 1740. Böttger ware was a very important step in making porcelain in Europe.

In Literature

The story of Johann Friedrich Böttger is featured in a book by Gustav Meyrink. It is called Goldmachergeschichten. In this book, Böttger's name is changed to Johann Friedrich Bötticher.

- Hans-Joachim Böttcher wrote a book called Böttger – Vom Gold- zum Porzellanmacher. It was published in Dresden in 2011. ISBN: 978-3-941757-31-8.

Böttger's story also appears in a novel by Bruce Chatwin. The book is called Utz and came out in 1988.

See also

In Spanish: Johann Friedrich Böttger para niños

In Spanish: Johann Friedrich Böttger para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |