John Ellis (physicist, born 1946) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

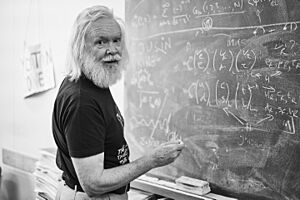

John Ellis

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1 July 1946 Hampstead, London, England, UK

|

| Nationality | British-Swiss |

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Proposing how to discover the gluon and the Higgs boson

Popularizing the term "Theory of Everything" |

| Awards | Mayhew Prize (1968) Maxwell Medal and Prize (1982) Paul Dirac Medal and Prize (2005) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Particle physics |

| Institutions | King's College London CERN |

| Thesis | Approximate symmetries of hadrons |

| Doctoral advisor | Bruno Renner |

John Ellis (born 1 July 1946) is a famous British-Swiss scientist. He is a theoretical physicist, which means he uses math and ideas to understand how the universe works at its smallest level.

John Ellis went to King's College, Cambridge in 1964. He earned his PhD in theoretical particle physics in 1971. He also spent time as a student at CERN, a big science lab in Europe. After working at other labs, he returned to CERN in 1973. He worked there as a staff member until he was 65. Since 2010, he has been a professor at King's College London. He still works at CERN as a visiting scientist.

At CERN, John Ellis did more than just research. He helped lead the theory division twice. He also helped choose experiments for giant particle accelerators like the LEP and the LHC. He also advised CERN's leaders on working with countries outside Europe. He was also the first person to lead CERN's group for equal opportunities.

Contents

Discovering the Universe's Secrets

John Ellis's research mainly focuses on particle physics. This field studies the tiny particles that make up everything. He has also made important discoveries in astrophysics (the study of stars and space) and cosmology (the study of the universe's origin).

Finding New Particles

Much of his work helps scientists understand what they see in experiments. He also explores what future particle accelerators could discover. He was one of the first to combine particle physics with cosmology. This new area is called particle astrophysics.

In 1976, John Ellis and his team suggested a way to find the Higgs boson. This particle helps explain why other particles have mass. They also figured out how the Higgs boson might break down. In the same year, he helped estimate how certain particles called kaons decay. This was later observed in experiments at CERN.

He also suggested a way to find the gluon in 1976. Gluons are particles that hold atomic nuclei together. The next year, he predicted the mass of the bottom quark. This was before scientists even saw this quark in experiments!

Exploring Supersymmetry

In the 1980s, John Ellis became a big supporter of supersymmetry models. Supersymmetry is a theory that suggests every known particle has a "superpartner." He showed that the lightest supersymmetric particle could be a candidate for dark matter. Dark matter is a mysterious substance that scientists believe makes up a large part of the universe.

In 1990, he showed that early data from the LEP accelerator supported supersymmetric models. These models try to combine all the forces of nature into one "Grand Unified Theory." He also helped analyze "benchmark scenarios." These are examples that show what scientists might expect to find if supersymmetry is real.

Testing Quantum Gravity

Besides supersymmetry, John Ellis has also looked into quantum gravity and string theory. These theories try to explain gravity at a very tiny level. He worked on tests of whether the speed of light is always the same. His work on string cosmology also won awards.

In 1996, he suggested looking for unusual radioactive materials in rocks. These materials could have come from a nearby supernova explosion. Scientists have since found some of these materials. This suggests that a star exploded close to Earth millions of years ago.

Understanding the Higgs Boson

After the Higgs boson was discovered in 2012, John Ellis and his student studied its properties. The Nobel Prize for the Higgs boson mentioned one of their papers. This paper stated that "Beyond any reasonable doubt, it is a Higgs boson."

Since 2019, he has been a key member of the AION project in the UK. This project uses special tools to search for very light dark matter and gravitational waves. He has also been exploring what the gravitational wave signals reported by pulsar timing arrays mean.

John Ellis has written over 1,000 scientific papers. These papers have been cited by other scientists over 120,000 times. In 2004, he was ranked as the second-most cited theoretical physicist.

Supporting Particle Accelerators

Besides his research, John Ellis has strongly supported building new particle accelerators. He supported the LEP and LHC. He also supports future projects like the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC). His theoretical work often connects to these accelerators. For example, he showed how data from accelerators could predict the masses of the top quark and the Higgs boson.

He played a big role in a 1984 workshop about what physics could be done with the LHC. He has written many articles about searching for Higgs bosons and supersymmetric particles at the LHC. He writes for both scientists and the general public.

John Ellis is currently a strong supporter of the FCC project. This project aims to build a future high-energy collider complex.

Awards and Recognitions

John Ellis has received many awards and honors for his work:

- 1968: Mayhew Prize

- 1982: Maxwell Medal

- 1985: Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London

- 1991: Elected a Fellow of the Institute of Physics

- 1999 and 2005: First Award in the Gravity Research Foundation essay competition

- 2005: Paul Dirac Prize of the Institute of Physics

- 2012: Made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his services to science and technology

- Since 1994: Has received 12 honorary doctorates and fellowships

Sharing Physics with the World

John Ellis often gives public talks about particle physics. He gives these talks in English, French, Spanish, and Italian. At CERN, he often gives introductory talks to visitors, including students and teachers.

He is also known for helping non-European countries get involved in CERN's science. He has worked with scientists, university leaders, and government officials from many countries. These include major partners like the United States, Japan, and China. He has also worked with countries that are just starting their physics programs. His efforts have helped make CERN a truly international place for science.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |