John Herivel facts for kids

John William Jamieson Herivel (born August 29, 1918 – died January 18, 2011) was a smart British science historian and a World War II codebreaker. He worked at a secret place called Bletchley Park during the war.

John Herivel is best known for discovering something called the Herivel tip (or Herivelismus). This clever idea helped the codebreakers at Bletchley Park figure out secret messages from the German Enigma machine. His discovery was based on how some German operators used their machines. For a short but very important time after May 1940, the Herivel tip, along with other operator mistakes, was the main way to break the Enigma code.

After the war, Herivel became a professor. He studied the history and philosophy of science at Queen's University Belfast. He was especially interested in famous scientists like Isaac Newton, Joseph Fourier, and Christiaan Huygens. Later, he wrote a book about his time at Bletchley Park called Herivelismus and the German Military Enigma.

Contents

Joining the Secret Team at Bletchley Park

John Herivel was born in Belfast. He went to Methodist College Belfast and later studied math at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. His teacher, Gordon Welchman, was the one who asked him to join the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park.

Welchman worked with Alan Turing in a new section called Hut 6. Their job was to break the Enigma codes used by the German Army and Air Force. John Herivel was only 21 when he arrived at Bletchley Park on January 29, 1940. Alan Turing and Tony Kendrick taught him about the Enigma machine.

Understanding the Enigma Machine

When John Herivel started at Bletchley Park, Hut 6 was having trouble breaking the Enigma codes. Most of these messages came from the German Air Force (Luftwaffe). Herivel worked with another mathematician, David Rees, trying to find solutions and figure out the machine's settings. It was a very slow process. Herivel was determined to find a faster way to break the codes. He spent his evenings thinking about new methods.

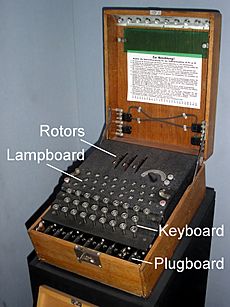

The Germans used the Enigma to encrypt their Morse code messages. The Enigma was an electro-mechanical machine with spinning parts called rotors. The main Enigma model in 1940 had three rotors. These rotors created an electrical path from the keyboard to a lampboard. When you pressed a key, a lamp lit up, showing the encrypted letter. Each time a key was pressed, the right-most rotor would move. This changed the electrical path, so pressing the same key again would light up a different letter.

The rotors also had notches. When a rotor reached a certain position, its notch would make the next rotor move too. This made the code very complex and hard to repeat. The three rotors were chosen from a set of five. This meant there were 60 different ways to put the rotors into the machine.

To decrypt the messages, the codebreakers needed to know which rotors were used, how their rings were set, and how the plugboard was connected. Bletchley Park had replica Enigma machines. These machines worked just like the German ones. German operators also used the first three letters of a message as an indicator. This told the receiving operator how to set their machine for that specific message.

The Herivel Tip: A Clever Idea for Codebreaking

In February 1940, John Herivel had a brilliant idea. He thought that some German code clerks might be a bit lazy. They might give away the Enigma's daily settings (called Ringstellung) in their very first message of the day. If many clerks were lazy, their first message settings wouldn't be random. Instead, they would cluster around the actual daily setting. This idea became known as the Herivel tip.

At first, this tip wasn't needed because the Germans were encrypting their message keys twice. Other methods, like Zygalski sheets, worked then. But in May 1940, the Germans stopped encrypting their keys twice. Suddenly, the old methods didn't work anymore. Bletchley Park started using the Herivel tip to break the German Air Force messages. It was the main method until the special codebreaking machines called bombes arrived in August 1940.

How Enigma Messages Were Sent

The rotors and the position of the ring with the notch were changed every day. The settings were written in a codebook that all operators on that network used. At the start of each day, operators would set up their Enigma machine with the day's rotor selection and ring settings. They could adjust the ring settings before or after putting the rotors into the machine.

Herivel thought it was likely that some operators would adjust the rings *after* the rotors were in the machine. After setting the rings and closing the lid, an operator was supposed to move the rotors far away from the settings that showed the three letters of the ring setting. But some operators didn't do this.

Herivel's big idea came to him one evening in February 1940. He was relaxing by the fire at his landlady's house. He thought that stressed or lazy operators, who set the rings while the rotors were in the machine, might then just leave the rotors at or near that setting. They might use those three letters for the first message of the day.

For each message, the sending operator followed a procedure. From September 1938, they would use an initial position to encrypt the indicator. This was sent in clear (unencrypted). Then came the message key, which was encrypted at that setting. For example, if the ground setting (German: Grundstellung) was GKX, the operator would set the Enigma to GKX. They would then encrypt the message setting, which they might choose as RTQ. This might encrypt to LLP. The operator would then turn their rotors to RTQ and encrypt the actual message. So, the beginning of the message would be the unencrypted ground setting (GKX), followed by the encrypted message setting (LLP). A receiving operator could use this to decrypt the message.

The ground setting (like GKX) was supposed to be chosen randomly. But Herivel thought that if operators were lazy or in a hurry, they might just use whatever rotor setting was already showing on the machine. If this was the first message of the day, and the operator had set the ring settings with the rotors already in the machine, the rotor position showing could be the ring setting itself, or very close to it.

Using the Herivel Square

The day after Herivel had his idea, his colleagues agreed it was a possible way to break Enigma. Hut 6 started looking for the effect Herivel predicted. They asked for the first messages of the day from each German station to be sent to them quickly. They plotted these indicators on a grid called a "Herivel square."

The rows and columns of the grid were labeled with the alphabet. The first indicator of the first message from each station was put into the grid. For example, if the indicator was GKX, an X would be placed in the cell where column G and row K met.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z ---------------------------------------------------------- Z| |Z Y| S |Y X| |X W| L |W V| |V U| E |U T| |T S| |S R| K |R Q| S |Q P| |P O| |O N| N |N M| X |M L| W T |L K| X Y |K J| W X |J I| |I H| Q |H G| |G F| |F E| A |E D| |D C| V |C B| J |B A| P |A ---------------------------------------------------------- A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

The Herivel tip suggested that there would be a group of entries close together, like the cluster around GKX in the example above. This would narrow down the possible ring settings from 17,576 to a much smaller number, perhaps 6 to 30. These could then be tested one by one.

At first, the pattern Herivel predicted didn't show up. Bletchley Park continued to use another method from Polish codebreakers. But everything changed on May 1, 1940, when the Germans changed their message procedure. The old method stopped working, and Hut 6 couldn't decrypt Enigma messages anymore.

Luckily, the pattern predicted by the Herivel tip started to appear soon after, on May 10, when the Germans invaded the Netherlands and Belgium. David Rees saw a cluster in the indicators. On May 22, a German Air Force message from May 20 was finally decoded. This was the first one since the Germans changed their procedure!

Other Parts of the Enigma Key

Even though the Herivel tip helped find the Enigma's ring settings, it didn't reveal other parts of the key. These included the order of the rotors and the plugboard settings. The German Air Force used 5 rotors, so there were 60 possible rotor orders. Also, the plugboard connected many letters, making the code even harder. Codebreakers had to use other methods to find these missing parts of the Enigma key.

The Herivel tip was used along with another type of operator mistake, called "cillies". Together, these helped solve the settings and decrypt the messages. The Herivel tip was used for several months until special codebreaking machines, called "bombes" and designed by Alan Turing, were ready.

How Important Was It?

Gordon Welchman wrote that the Herivel tip was super important for breaking Enigma at Bletchley Park. He said that if Herivel hadn't been there, they might have been defeated in May 1940. They wouldn't have been able to keep breaking the codes until the bombes arrived months later.

Because his contribution was so vital, Herivel was specially introduced to Winston Churchill during a visit to Bletchley Park. He also taught Enigma cryptanalysis to a group of Americans in a two-week course. Later, Herivel worked in the "Newmanry" section. This group used machines like the Colossus computers to solve German teleprinter codes. He was the assistant to the head of that section, mathematician Max Newman.

In 2005, researchers found that the clustering predicted by the Herivel tip also appeared in Enigma messages from August 1941.

Life After World War II

After the war, John Herivel taught math at a school for a year. But he found it hard to handle the "rumbustious boys." So, he joined Queen's University Belfast. There, he became a reader (a type of professor) in the History and Philosophy of Science.

One of his students was the actor Simon Callow. Simon Callow said that Herivel was a wonderful teacher. He would make tea and toast crumpets during his tutorials. He was a very deep thinker but also very unexpected in his ways. Simon Callow also noted that Herivel didn't seem to think he had done anything extraordinary in his life.

Herivel wrote books and articles about famous scientists like Isaac Newton, Joseph Fourier, and Christiaan Huygens.

In 1978, he retired to Oxford. He became a Fellow at All Souls College. He passed away in Oxford in 2011.

He is survived by his daughter Josephine Herivel.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |