John Murray of Broughton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir John Murray of Broughton, 7th Baronet of Stanhope

|

|

|---|---|

Modern Broughton Place; built on site of Murray's birthplace in 1935, based on the original 17th century design

|

|

| Jacobite Secretary of State | |

| In office August 1745 – May 1746 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 October 1715 Broughton, Peebleshire |

| Died | 6 December 1777 (aged 62) Cheshunt, Hertfordshire |

| Resting place | East Finchley Cemetery, London |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Spouses | (1) Margaret Ferguson 1739–1749 (2) Miss Webb |

| Children | Numerous; including David (1743–1791), Robert (1745–1793), Lt-General Thomas Murray (ca 1749–1816) Charles Murray (1754–1821) |

| Parents | Sir David Murray (ca 1652–1729) Margaret Scott |

| Alma mater | Edinburgh University Leiden University |

| Occupation | Politician and landowner |

Sir John Murray of Broughton (born around 1715 – died 1777) was a Scottish nobleman. He is also known as Murray of Broughton. He played a key role in the 1745 Jacobite Rising. During this time, he served as the Secretary of State for the Jacobite cause.

His job was to manage the everyday running of the Jacobite government. People at the time said he worked very hard and was good at his job. After the Battle of Culloden in 1746, he was captured. He then gave information against Lord Lovat, who was later executed. Murray's information mostly pointed to people who had promised to help the Rising but didn't.

He was set free in 1748 and lived a quiet life until he died in 1777. Some of his old friends called him a traitor. However, he always kept his Jacobite beliefs. He was also one of the few people who stayed friends with Prince Charles.

Contents

John Murray's Early Life and Family

John Murray was born in Broughton, Scotland. He was the younger son of Sir David Murray and his second wife, Margaret Scott. His father had taken part in an earlier uprising, the 1715 Rising. However, he was forgiven and worked to make his family rich again. In 1726, his father sold their lands in Broughton. He used the money to buy new lands and lead mines.

In 1739, John Murray married Margaret Ferguson. They had five children together, including three sons. These sons were David (born 1743), Robert (born 1745), and Thomas (born around 1749).

Later, Murray had more children with a woman named Miss Webb. One of their most famous children was Charles Murray (born 1754). He became a well-known actor and writer.

John Murray's nephew, Sir David, also joined the 1745 Rising. He lost his lands and title because of it. He was allowed to leave the country and died in 1752. The title of Baronet of Stanhope was given back in the 1760s. John Murray received it in 1770, and then his eldest son David got it in 1777.

Murray's Role in the Jacobite Cause

Before the 1745 Rising

Murray studied at the University of Edinburgh from 1732 to 1735. Then he went to the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. In 1737, he went on a "Grand Tour." This was a trip around Europe that many rich young men took. On this trip, he visited Rome. One of the interesting things to see there was James Stuart, who was living in exile.

The Jacobite cause had been quiet for a while. When Murray met James, James was living peacefully. He had given up hope of becoming king. Most visitors just saw the exiled royal family. But in August, Murray joined a special club in Rome called a Masonic lodge. James's private secretary was also a member. This club was known for having many Jacobite supporters. This seems to be how Murray started his work for the Jacobite cause.

Murray returned to Scotland in December 1738. He married Margaret Ferguson and bought back his family's estate, Broughton. In 1741, the Duke of Hamilton chose him to be the main Jacobite agent in Scotland.

In 1740, the War of the Austrian Succession began. Britain and France were on opposite sides. Murray often visited Paris to carry messages. He passed notes between Scottish Jacobites and the Stuart agent in Paris. After a battle in 1743, the French King Louis XV wanted to distract Britain. He planned to invade England in 1744 to bring back the Stuarts. Prince Charles secretly joined the invasion force. But the plan was canceled when a storm damaged the French ships.

In August, Charles went to Paris to get French support for another attempt. He met Murray there. Charles told him he would go to Scotland "even with a single footman." Back in Edinburgh, Murray told a pro-Jacobite club about this. Murray and others wrote to Charles. They told him not to come unless he brought 6,000 French soldiers, money, and weapons. This letter was given to a nobleman to deliver, but he didn't.

Murray as Secretary: The 1745 Rising

In late June, Murray learned Charles was sailing from France. He waited in Western Scotland for three weeks. He hoped to convince Charles not to land. He eventually gave up and was home when Charles arrived on July 23. When Charles refused to go back to France, Murray agreed to become his Secretary.

This meant Murray was in charge of the everyday running of the Jacobite side. He also handled their money. Money was a big problem, as Charles had very little cash. One way they got money was by collecting taxes. Many towns had to pay taxes twice. The government didn't accept the Jacobite taxes.

The Jacobite army marched to Edinburgh. They reached Perth on September 3. There, Lord George Murray joined them. Lord George had been in earlier uprisings. He was forgiven in 1725 and lived as a country gentleman. His joining surprised everyone. Many Jacobites didn't trust him. Murray was later blamed for fights between Charles and Lord George. But Lord George was known for his quick temper and not taking advice.

Murray went with the army into England. He helped with the surrender of Carlisle in November. He was not part of the Prince's War Council. So, he wasn't responsible for the decision to retreat at Derby. This retreat made the relationship between Charles and the Scots much worse. Murray was one of the few Charles still trusted.

After giving up on the siege of Stirling in February, the Jacobites went back to Inverness. In March, Murray got sick. A less capable person took his place.

Money and basic things like shoes were very scarce. Soldiers were paid with oatmeal. Supplies were taken from local shops. In April, the leaders decided they needed a big win. But they lost the Battle of Culloden. Charles told his soldiers to scatter until he returned with more help from France.

In early May, two French ships arrived. They brought 35,000 gold coins for the Jacobite war. The British Navy was close behind. The money was quickly brought ashore. The French ships fought their way out. They carried away several important officers. Murray was trying to get to Holland when he heard about the ships. He hoped to use the money to keep fighting. He and others went to get the money. One barrel was missing.

What happened to the rest of the money is unclear. Murray said some was paid to soldiers. He said most was given to someone else for safekeeping. In the arguments after the defeat, many people were accused of stealing it. Even today, treasure hunters haven't found any trace of it.

A few days later, Murray and other Jacobite leaders met near Loch Morar. They talked about their options. Lord Lovat joined them. He had avoided fighting himself. But he had sent 300 of his clansmen to join. Everyone agreed to meet again soon. They would use the French money to pay their men. But when they met again, many people didn't show up.

Plans to keep fighting were given up. Government forces were looking for them. The group split up. Murray was still hoping to leave from Leith. He was also very sick. He went to his sister's house. He was arrested there on June 27. In early July, he was taken to the Tower of London. Other important Jacobites were also there.

Trial and Later Life

Before the 1744 invasion attempt, James had given Murray an officer's rank. At his trial, Murray said this meant he should be treated as a prisoner of war. He argued he was not a rebel. But the court disagreed.

Most high-ranking Jacobite prisoners had already been sentenced. But Murray agreed to give information to the court. In return, he would receive a pardon. Some people say Murray's information led to Lord Lovat's execution. But it was mostly used to confirm details already known. Lovat's involvement was not a secret. Many people at the time felt his execution was long overdue.

More importantly, Murray gave information about supporters who didn't help the Rising. He avoided naming people he hadn't met. No action was taken against many of these people. But this ended a practice where some politicians could support overthrowing the government without punishment.

After Lovat's execution, Murray was released from the Tower. He was officially pardoned in June 1748. He then lived a quiet life. He bought a house outside London. It is said that Prince Charles visited him there in 1763. Murray remarried and had six more children.

How History Views Murray

It's hard to judge Murray because arguments about why the Rising failed caused big disagreements among the Jacobites. Some people accused him of making Charles and Lord George Murray fight. But these accusers were not fair witnesses.

Some historians claimed Murray strongly supported the plan to go to Scotland. They said he told Charles about many promises of support. But most evidence shows Charles wanted to try even before meeting Murray. Many people he spoke to strongly told him not to go.

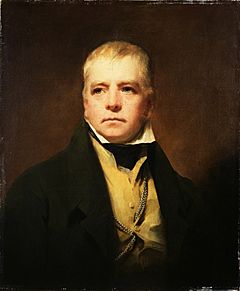

Most accusations of "betrayal" came from people who didn't keep their promises of support. Murray later wrote that good actions are admired even by those who are not brave enough to do them. Many stories about Murray come from a book called Tales of a Grandfather. This book was written by the novelist Sir Walter Scott in 1828. While the events are mostly correct, few of his stories can be proven.

One famous story says that when asked if he knew Murray, someone replied, "Once I knew...a Murray of Broughton, but that was a gentleman and a man of honour." Another story claims Murray visited Scott's father, who was his lawyer. After each meeting, his father would throw out anything Murray had used. He would say, "I may admit into my house...persons wholly unworthy to be treated as guests... Neither lip of me nor of mine comes after Mr. Murray of Broughton's." Neither of these stories is true. Most of Scott's stories about the Rising are made up.

Images for kids

| Baronetage of Nova Scotia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir David Murray (nephew) |

Baronet (of Stanhope) 1770–1777 |

Succeeded by Sir David Murray (son) |

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |