John Stapp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Stapp

|

|

|---|---|

Stapp in his Air Force uniform

|

|

| Born |

John Paul Stapp

July 11, 1910 |

| Died | November 13, 1999 (aged 89) Alamogordo, New Mexico, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Fort Bliss National Cemetery El Paso, Texas, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Baylor University (B.A. 1931, M.A. 1932) University of Texas (Ph.D., 1940) University of Minnesota (M.D., 1944) |

| Known for | Study of deceleration on humans, Stapp's Law |

| Awards | Elliott Cresson Medal (1973) Gorgas Medal (1957) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics (Acceleration) Physician and Medicinal science |

Colonel John Paul Stapp (born July 11, 1910 – died November 13, 1999) was an American officer in the United States Air Force. He was a flight surgeon and a physician. He was also a biophysicist who studied how the human body reacts to strong forces. These forces include acceleration (speeding up) and deceleration (slowing down very quickly). He worked with Chuck Yeager and was known as "the fastest man on earth." His work helped the U.S. space program, especially with Project Manhigh.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Stapp was born in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil. He was the oldest of four sons. His parents, Charles Franklin Stapp and Mary Louise Shannon, were Baptist missionaries. John went to high school in Texas at Brownwood High School and San Marcos Baptist Academy.

He earned several degrees from different universities. In 1931, he got a bachelor's degree from Baylor University. The next year, he earned a master's degree from Baylor. In 1940, he received a PhD in Biophysics from the University of Texas at Austin. Finally, in 1944, he earned his medical degree (MD) from the University of Minnesota. He also spent a year working at St. Mary's Hospital in Duluth, Minnesota. Later, Baylor University gave him an honorary Doctor of Science degree.

Military Career and Early Research

John Stapp joined the U.S. Army Air Forces on October 5, 1944, as a doctor. He also became a flight surgeon, which is a doctor who specializes in the health of pilots and aircrew. In 1946, he started working at the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. There, he became a project officer and medical expert in the Biophysics Branch. When the U.S. Air Force became its own branch of the military in 1947, Stapp transferred to it.

One of his first jobs was to test different oxygen systems. He flew in planes without pressurized cabins at very high altitudes, around 40,000 feet (12.2 km). A big problem with flying so high was the danger of "the bends." This is a painful condition caused by gas bubbles forming in the body. Stapp's research helped solve this and other problems. His work made it possible for new high-altitude aircraft to be developed. It also helped create techniques like HALO (High Altitude-Low Opening) parachute jumps. In March 1947, he was assigned to a special project studying deceleration.

In 1967, the Air Force sent Stapp to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. There, he worked on research to make cars safer. He retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1970 as a Colonel.

Studying Deceleration Effects

By 1945, military experts realized they needed to study how quickly slowing down affected the human body. This research aimed to make aircraft safer for people during crashes. The first part of the program was to build special equipment. This equipment could simulate plane crashes. It also helped study how strong seats and harnesses needed to be. They also wanted to see how much deceleration humans could handle in these simulated crashes.

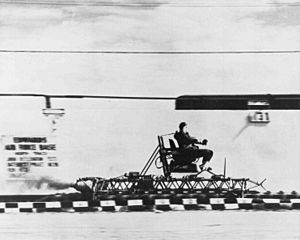

The first test run on the rocket sled happened on April 30, 1947. It carried only weights, and the sled went off the tracks. The first test with a human volunteer took place in December of that year. The measuring tools were still being developed in the early runs. It wasn't until August 1948 that they were good enough to record accurate data. By August 1948, sixteen human runs had been completed. All of these tests had the subjects facing backward. Tests with subjects facing forward began in August 1949. Many early tests compared standard Air Force harnesses with new, improved ones. The goal was to find out which harness offered the best protection for pilots.

By June 8, 1951, a total of 74 human runs had been made on the decelerator. Nineteen of these runs had subjects facing backward, and 55 had them facing forward. Stapp often volunteered for these dangerous runs. He broke his right wrist twice during the tests. He also broke ribs, lost tooth fillings, and had bleeding in his eyes that caused temporary vision loss. In one test, he survived forces up to 38 times the force of gravity (38 g).

Stapp's research had a huge impact on both civilian and military aviation. For example, the idea of backward-facing seats became very important. His research proved that this position was the safest for aircraft passengers. It showed that people could handle much greater deceleration when facing backward. As a result, many military transport planes were equipped with these seats. Commercial airlines learned about these findings, but they still use forward-facing seats. The British Royal Air Force also put backward-facing seats in many of their military transport planes.

Because of Stapp's discoveries, the strength required for fighter jet seats was greatly increased. His work showed that a pilot could survive a crash if properly protected by harnesses and if the seat stayed in place.

Stapp also helped develop the "side saddle" or sideways-facing harness. This new triangular harness gave much better protection to paratroopers. It was made of strong nylon webbing. It fit snugly over the shoulder facing the front of the aircraft. This harness protected the wearer from crash impacts, takeoffs, and landing bumps. It could withstand about 8,000 lbf (35,600 N) of force. It was designed to replace older lap belts, which did not offer enough protection.

On December 10, 1954, Stapp made his 29th and last ride on the decelerator sled. This happened at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. He showed that a human can withstand at least 46.2 g (when facing forward with good harnesses). This is the highest known acceleration a human has ever willingly experienced. Stapp reached a speed of 632 mph (1,017 km/h), which broke the land speed record. This made him the fastest man on Earth. Stapp believed that humans could handle even more acceleration than what was tested.

Stapp also helped create an improved version of the shoulder strap and lap belt used today. This new, stronger harness could withstand 45.4 g (445 m/s²). The old combination could only handle 17 g (167 m/s²). The new pilot harness added an upside-down "V" strap across the pilot's thighs. This strap connected to the standard lap belt and shoulder straps. All the straps fastened at one point. This spread the pressure evenly over the body's stronger areas, instead of just on the stomach.

Wind-Blast Experiments

Stapp also took part in wind-blast experiments. In these tests, he flew in jet aircraft at high speeds. The goal was to see if a pilot could safely stay in their plane if the cockpit canopy accidentally blew off. Stapp stayed in his aircraft at a speed of 570 mph (920 km/h) with the canopy removed. He did not suffer any injuries from the strong wind. He also supervised research programs about how pilots could safely escape from aircraft.

Stapp's Law

John Stapp loved collecting wise sayings and proverbs. He kept a special book for them, and this habit spread to his team. In 1992, he published a collection of these sayings. Stapp is known for popularizing, and also for writing the final version of, the saying known as Murphy's law: "Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong."

Stapp is also credited with creating Stapp's Law (sometimes called Stapp's Ironic Paradox). It says: "The universal aptitude for ineptitude makes any human accomplishment an incredible miracle." This means it's amazing that humans achieve anything, given how often things can go wrong!

Awards and Recognition

- In 1957, he received the Gorgas Medal from the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States.

- In 1973, Stapp was given the Franklin Institute's Elliott Cresson Medal.

- In 1979, Stapp was added to the International Space Hall of Fame. The museum has a John P. Stapp Air & Space Park. This park includes Sonic Wind No. 1, which is the rocket sled Stapp rode.

- In 1985, Stapp was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame for his important work in aviation safety.

- In 1991, Stapp received the National Medal of Technology. This award was for his research on how mechanical force affects living things. His work led to many safety improvements in crash protection technology.

- In 2012, 13 years after he passed away, Stapp was given the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers award. This award honors people who played a big part in the history of Air Force space and missile programs.

Later Life

In the years before he died, John Stapp was the president of the New Mexico Research Institute. This institute was located in Alamogordo, New Mexico. He also chaired the yearly Stapp Car Crash Conference. This event brings together experts to study car crashes and find ways to make cars safer. Stapp was also the honorary chairman of the Stapp Foundation. This foundation, supported by General Motors, provides scholarships for students studying automotive engineering.

John Stapp passed away peacefully at his home in Alamogordo at the age of 89.

See also

In Spanish: John Stapp para niños

In Spanish: John Stapp para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |