John W. Jones (ex-slave) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

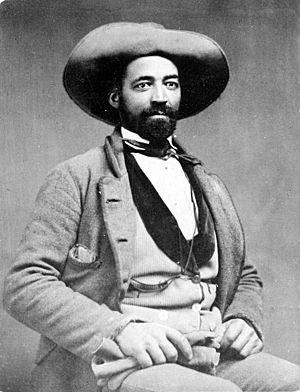

John W. Jones

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 21, 1817 |

| Died | December 26, 1900 (aged 83) |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery |

| Known for | Conductor on the Underground Railroad |

| Spouse(s) | Rachel Jones (née Swails) |

John W. Jones (June 21, 1817 – December 26, 1900) was an amazing American hero. He was born into slavery in Leesburg, Virginia. Later, he became a key figure in the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network that helped people escape slavery. Jones helped hundreds of people find freedom. He is buried in Woodlawn National Cemetery in Elmira, New York.

Contents

John W. Jones: A Journey to Freedom

Early Life and Daring Escape

John W. Jones was born on a plantation in Virginia in 1817. He was enslaved by the Ellzey family. As a young boy, he worked as a houseboy for Miss Sally Ellzey. She was kind to him, but as she grew older, John worried about his future. He feared he might be sold to another plantation.

So, on June 3, 1844, John decided to escape. He left with his two half-brothers, George and Charles. Two other enslaved men, Jefferson Brown and John Smith, joined them. They followed the secret routes of the Underground Railroad. Their journey took them through Williamsport, Canton, Alba, and South Creek.

During their escape, John and his friends had to fight off slave hunters in Maryland. They finally made it to the free state of Pennsylvania. They kept heading north into New York State. There, they found safety in a barn on South Creek Farm. Dr. Nathaniel Smith owned the farm. Mrs. Smith found the tired and hungry men. She cared for them until they could continue their journey. It is said that John was so thankful that flowers mysteriously appeared on Mrs. Smith's grave after she died. This continued until John himself passed away. The five men finally reached Elmira on July 5, 1844.

Helping Others to Freedom

Elmira's Role in the Underground Railroad

Elmira became John Jones's new home. It was a very important stop on the Underground Railroad. Many people escaping slavery passed through Elmira. They often came from Harrisburg and Williamsport. From Elmira, they would continue their journey to places like Rochester or St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada. Canada was a final destination for many seeking freedom.

Elmira's location was perfect for the Underground Railroad. It was right between Philadelphia and St. Catharines. In July 1845, for example, 17 people escaping slavery were hiding in the Elmira area. They found shelter on farms and in other secret spots.

After 1850, the Northern Central Railway was completed. This made Elmira even more important for the Underground Railroad. People escaping slavery could now hide in baggage cars. This made their journey faster and safer.

Jones's Secret Work

John Jones became an active "agent" for the Underground Railroad in 1851. By 1860, he had helped 860 enslaved people escape to freedom. He usually welcomed groups of six to ten people at a time. But sometimes, he found shelter for as many as 30 men, women, and children in one night. It is believed that John often hid these brave people in his own home. His house was located behind the First Baptist Church. Out of the 860 people he helped, not one was ever caught or sent back to the South.

In 1854, train tracks from Williamsport to Elmira were finished. John Jones made a special deal with the Northern Central Railway workers. He would hide the freedom seekers in the 4 o'clock "Freedom Baggage Car." This train would take them directly to Niagara Falls. From there, most of Jones's "baggage" (the people he helped) eventually reached St. Catharines, Canada.

Life in Elmira: Work and Community

Early Jobs in Elmira

When John first arrived in Elmira, he took on many different jobs. He chopped wood, worked in a candle shop, and cleaned as a janitor. One of his jobs was cleaning for Miss Clara Thurston's school for young ladies.

Sexton at First Baptist Church

In 1847, John Jones became the sexton of Elmira's First Baptist Church. A sexton is someone who takes care of the church building and grounds. He bought a house right next to the church for $500. As sexton, John kept careful records of everyone buried in the Second Street Cemetery.

Back then, Elmira did not have a paid fire department. Volunteer firefighters would rush to John's "yellow house." They needed him to go to the church and ring the bells. This was the signal to call other volunteers to a fire. After other churches got bells, it became a friendly contest. Each sexton tried to be the first to ring the alarm. The first sexton to ring their bell would get $2.00 from the fireman. John usually won this contest! He was clever and tied one end of a rope to the bell's clapper. The other end he tied to his bedpost. This way, he could ring the bell quickly from his bed.

John Jones served as the sexton for First Baptist Church for 43 years.

Burying Confederate Soldiers

During the American Civil War, Elmira had a prison camp for Confederate soldiers. Many prisoners died there. John Jones was given the important job of burying these soldiers at Woodlawn National Cemetery. He was incredibly careful with his records. Out of the 2,963 prisoners he buried, only seven were listed as unknown.

John's detailed records were so good that on December 7, 1877, the government made the burial site a national cemetery. In 1907, thanks to his records, the government was able to place accurate headstones on almost all of the 2,973 Confederate graves.

John made sure each coffin was clearly marked. He put any information the soldier had shared into a sealed bottle inside the coffin. Any valuable items the soldier had were carefully listed and stored. The graves were marked with wooden markers. They were arranged as if soldiers were lined up for inspection. Union soldiers' graves surrounded them, as if still on guard. When families received the precious photos, treasures, and letters John had kept, they were very touched. Only three bodies were ever moved for reburial.

John even helped the family of the Ellzeys' overseer. When the overseer's son, John R. Rollins, died at the prison camp, Jones arranged to send his body back home. A few years after the war, John Jones even visited the Ellzey plantation where he had been enslaved. He was welcomed warmly.

John received $2.50 from the government for each Confederate soldier he buried. This money helped him buy his College Avenue farm. He became known as the wealthiest Black man in that part of the state. The John W. Jones House still stands today on the original farm property.

Personal Life

John W. Jones married Rachel Jones (whose maiden name was Swails) in 1856. Rachel was the sister of Stephen Atkins Swails. John and Rachel had three sons and one daughter. Sadly, one of their sons, George Henry Jones, died on October 20, 1864, when he was only three years old.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |