Joseph Carter Corbin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

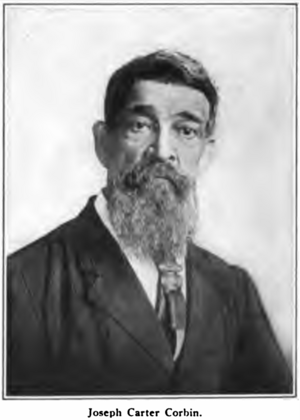

Joseph Carter Corbin

|

|

|---|---|

Corbin in 1887.

|

|

| Born | March 26, 1833 |

| Died | January 9, 1911 (aged 77) |

| Alma mater | Ohio University |

| Occupation | Educator, journalist |

| Political party | Republican |

Joseph Carter Corbin (born March 26, 1833 – died January 9, 1911) was an important journalist and teacher in the United States. Before slavery ended, he helped people escape to freedom through the Underground Railroad. He also worked as a journalist and teacher in Ohio and Kentucky.

After the American Civil War, he moved to Arkansas. There, he became the superintendent of public schools from 1873 to 1874. He is famous for starting the school that later became the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. He was its first principal from 1875 to 1902. Later, he was the principal of Merrill High School in Pine Bluff for ten years.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Joseph Carter Corbin was born in Chillicothe, Ohio, on March 26, 1833. His parents, William and Susan Corbin, were from Richmond, Virginia. They had been enslaved before moving to Chillicothe. Joseph was their oldest son.

He went to school in Chillicothe. One of his classmates was John Mercer Langston, who became a famous leader. When Joseph was 15, he moved to Louisville, Kentucky. There, he taught in schools as an assistant to Henry Adams. Henry Adams later became his brother-in-law.

After a few years, Joseph moved back to Ohio. He attended Ohio University and graduated in 1853. He then returned to Louisville. He worked as a clerk in a store and later in a bank. He also secretly helped people escape slavery as part of the Underground Railroad.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), Corbin worked as an editor. He published a newspaper called the Colored Citizen in Cincinnati. He was also part of a "colored school board committee" with other Black leaders. After the war, he received advanced degrees from his university.

Career in Arkansas

In 1872, Corbin moved to Arkansas. He was hired as a reporter for the Arkansas Daily Republican newspaper. He then became the chief clerk of the Little Rock Post Office.

In 1873, he was appointed the state superintendent of public schools. He held this important job for two years. Because of his position, he also served as the second president of the University of Arkansas Board of Trustees. While he was president, he signed the contract to build the first main building at the University of Arkansas.

Corbin strongly encouraged the creation of a new school for Black students. In 1873, the state approved the Branch Normal College in Pine Bluff. This school was meant to be the Black branch of the state university. It later became the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Corbin lost his job as superintendent after a political conflict in 1874. He then taught at the Lincoln Institute in Missouri for two years.

Leading Branch Normal College

In 1875, Governor Augustus H. Garland asked Corbin to return to Arkansas. He was sent to Pine Bluff to start the Branch Normal College. Nothing had been done to open the school since the law was passed in 1873.

Normal schools were special schools designed to train teachers. Corbin was very successful in his work. When the school opened in 1875, it had only seven students. By 1887, the number of students grew to about 250. From 1875 until 1883, Corbin was the only teacher at the school.

Corbin was the principal of Branch Normal College until 1902. He believed in the school's mission to provide a broad education. However, in the 1890s, the school began to focus more on industrial education. This was a type of training for specific trades, like the model used at Tuskegee University. Corbin did not fully agree with this change.

Challenges at the College

In 1891, the Arkansas Legislature passed a new law about funding for colleges. Corbin wanted the money to be fairly divided between white and Black universities. His efforts helped the school get $5,000 for new programs. These programs were in agriculture and mechanical arts.

However, a white employee from the University of Arkansas was hired to run these new programs. Corbin was not happy because he felt agriculture did not offer enough opportunities for his students to advance.

In 1893, Corbin faced an investigation. There were rumors about his performance. This was surprising because an earlier investigation in 1891 found him to be very successful. Some people believe the negative report was linked to his support for John M. Clayton. Clayton was a friend of Corbin and a powerful Republican politician.

The legislature could not remove Corbin from his job. The university's board of trustees decided to keep him. However, they promoted the white employee to a higher role. This put Corbin in a less powerful position. His relationship with the board continued to worsen. In June 1902, the board voted to replace him. They appointed Isaac Fisher as the new principal. Many people in the community supported Corbin and wanted him to return.

Later Career and Community Work

After leaving the university, Joseph Corbin became the principal of Merrill High School in Pine Bluff. He served there from 1901 to 1911. During this time, he helped create the Arkansas Teachers Association with R. C. Childress.

Corbin was a Baptist and led Sunday Schools in Pine Bluff for many years. He was also a key member of the Freemasons, a community organization. He was a talented musician and wrote articles about mathematics for education journals. From 1878 to 1881, he was the Third State Grand Master of the Prince Hall Freemasons of Arkansas. In 1903, he played a big part in building a new Masonic temple in Pine Bluff.

Personal Life

Joseph Corbin married Mary J. Ward on September 11, 1866, in Cincinnati, Ohio. They had six children together. His sister, Margaret, married Henry Adams, who was Joseph's former teaching assistant. Their son, John Quincy Adams, became a journalist. Joseph Carter Corbin passed away in Pine Bluff on January 9, 1911.

Sources

- Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880-1920. University of Georgia Press, 2007.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |