Kinetoscope facts for kids

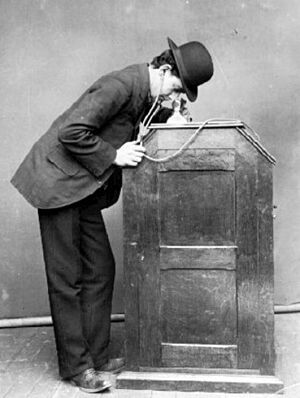

The Kinetoscope was an early machine that showed moving pictures. It was designed for just one person to watch at a time through a small window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector that showed films on a big screen. Instead, it used a strip of film with many pictures on it. This film moved quickly past a light, creating the illusion of movement.

The famous American inventor Thomas Edison first thought of the idea in 1888. His employee, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, and his team worked on it from 1889 to 1892. Dickson and his team also created the Kinetograph. This was a special movie camera that could take many pictures very quickly. They used it to make movies for the Kinetoscope.

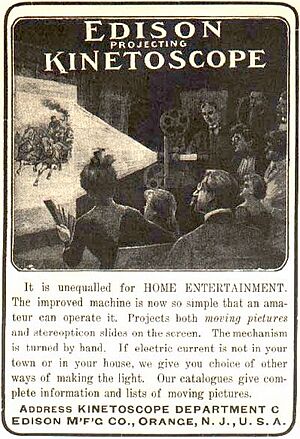

The first Kinetoscope was shown to a small group in May 1891. The finished version was shown in Brooklyn two years later. On April 14, 1894, the first commercial movie showing happened in New York City. Ten Kinetoscopes were used. The Kinetoscope was very important for the start of American movie culture. It also had a big impact in Europe. Edison decided not to get international patents for the device. This made it easier for others to copy and improve the technology. In 1895, Edison introduced the Kinetophone, which added sound from a phonograph cylinder to the Kinetoscope. Soon, movie projectors became more popular than the Kinetoscope's single-viewer system. Later, Edison's company made other movie systems called Projecting Kinetoscope.

Contents

How the Kinetoscope Was Developed

Thomas Edison became interested in making a motion picture system after seeing the work of Eadweard Muybridge. On February 25, 1888, Muybridge showed his zoopraxiscope in Orange, New Jersey. This device projected images drawn on a glass disc to create the illusion of movement. Edison's lab was nearby, and he or his photographer, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, might have seen the demonstration.

A few days later, Muybridge and Edison met. They talked about combining the zoopraxiscope with Edison's phonograph to play sound and images together. This combination never happened. However, in October 1888, Edison filed a preliminary claim with the U.S. Patent Office. He announced his plan to create a device that would do "for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear." He imagined seeing and hearing a whole opera perfectly. In March 1889, he filed another claim. This time, the device was named Kinetoscope. The name comes from Greek words meaning "movement" and "to view."

Who Invented the Kinetoscope?

Edison gave the job of creating the Kinetoscope to Dickson, one of his most skilled employees. While Edison took all the credit, many historians agree that Dickson did most of the work. The Edison lab was a team effort. Assistants worked on projects while Edison supervised and participated.

Dickson and his assistant, Charles Brown, had a slow start. Edison's first idea was to record tiny pictures, 1/32 of an inch wide, directly onto a cylinder. This cylinder was coated with a photographic material. A separate audio cylinder would play synchronized sound. The images were viewed through a microscope-like tube. When they tried making images a bit bigger, the quality was not good enough.

Around June 1889, the lab started using flexible celluloid sheets. These sheets, supplied by John Carbutt, could be wrapped around the cylinder. This provided a much better surface for recording photos. The first film made for the Kinetoscope, and possibly the first motion picture on film in the U.S., might have been shot then. It was called Monkeyshines, No. 1 and showed a lab employee moving around. They soon stopped trying to synchronize sound. Dickson also experimented with disc-based designs.

The project moved forward after Edison's trip to Europe and the World's Fair in Paris in 1889. While there, Edison met scientist Étienne-Jules Marey. Marey had invented a "chronophotographic gun"—the first portable movie camera. It used a strip of flexible film to capture images at 12 frames per second.

After returning to the U.S., Edison filed another patent claim on November 2. It described a Kinetoscope that used a flexible filmstrip. This film was perforated (had holes) so that sprockets could move it smoothly. The first system to use perforated film was the Théâtre Optique, patented by Charles-Émile Reynaud in 1888. Reynaud's system used painted images, not photographic film. At the World's Fair, Edison also saw the electrical tachyscope by German inventor Ottamar Anschütz. This device used a flashing light to "freeze" each image. This helped viewers see the many small changes in movement, making the illusion of motion very effective. By late 1890, this "intermittent visibility" was a key part of the Kinetoscope's design.

The Role of Filmstrips

There is some debate about when the Edison lab started using filmstrips. Dickson said he began cutting celluloid sheets into strips in mid-1889. He also claimed he saw George Eastman's new flexible film in August and used a roll for experiments. Historian Marta Braun says Eastman's film was strong and flexible enough for fast, continuous movement without tearing. This helped solve key problems in making movies.

Some scholars, like Gordon Hendricks, argue that the lab started using filmstrips much later. They believe Dickson and Edison changed the dates to protect their patents and reputation. However, the lab definitely ordered roll film from Eastman in September 1889, while Edison was still in Europe. They placed three more orders in the next five months.

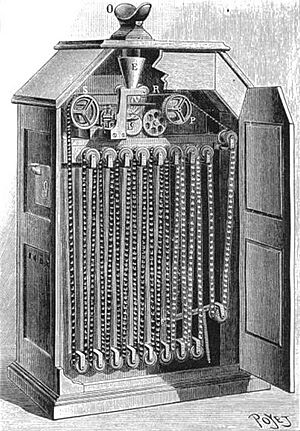

Work on the Kinetoscope was slow for much of 1890. Dickson was busy with another of Edison's projects. But by early 1891, Dickson and his new assistant, William Heise, had a working film viewing system. The new Kinetoscope was in a wooden cabinet. A loop of 3/4-inch (19 mm) film ran around several spindles. The film had one row of holes that an electric sprocket wheel used to pull it continuously. An electric lamp shone up from below the film. The images were projected through a magnifying lens and then through a peephole at the top of the cabinet.

The device also had a fast-spinning shutter. This shutter created a quick flash of light for each frame. This made each frame appear "frozen" for a moment. Because of how our eyes work (called persistence of vision), this rapid series of still frames looked like a moving image. The lab also developed the Kinetograph, a motor-powered camera that could shoot with the new perforated film. To make the film stop and go in the camera, allowing each frame to be fully exposed, they used a special escapement disc mechanism. This was the first practical system for the fast stop-and-go film movement that became the basis for movies for the next century.

On May 20, 1891, the first demonstration of a Kinetoscope prototype was held for about 150 women from the National Federation of Women's Clubs. The New York Sun newspaper described what they saw: "In the top of the box was a hole perhaps an inch in diameter. As they looked through the hole they saw the picture of a man. It was a most marvelous picture. It bowed and smiled and waved its hands and took off its hat with the most perfect naturalness and grace. Every motion was perfect...." The man in the film was Dickson himself. This short movie, about three seconds long, is now called Dickson Greeting.

On August 24, three detailed patent applications were filed. One was for the "Kinetographic Camera," and another for the "Apparatus for Exhibiting Photographs of Moving Objects" (the Kinetoscope). In the camera application, Edison said he could take up to 46 photos per second. However, he noted that 30 pictures per second or even slower could be enough for some subjects. According to the Library of Congress, Dickson Greeting and other films from 1891 were shot at 30 frames per second or slower. The Kinetoscope application also included a plan for a 3D film projection system, but this was later dropped.

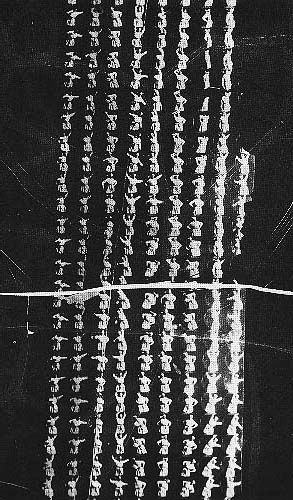

In early 1892, they started adding a coin slot to the Kinetoscope so people could pay a nickel to watch. By the end of the year, the Kinetoscope's design was mostly finished. The filmstrip was 1 3/8 inches wide. Each rectangular image was 1 inch wide by 3/4 inch high, with four holes on each side. Within a few years, this basic format, known as 35 mm, became the worldwide standard for movie film, and it still is today.

The patent for the Kinetograph's film movement system was issued on February 21, 1893. The Kinetoscope itself, which used intermittent lighting (not intermittent film movement), finally received its patent on March 14. The Kinetoscope was ready to be shown to the public.

The Kinetoscope Goes Public

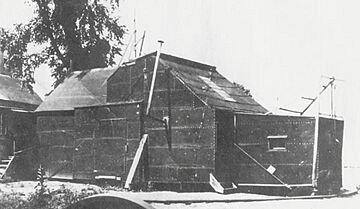

The first public showing of the finished Kinetoscope was at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893. The first film shown was Blacksmith Scene. It was directed by Dickson and filmed by Heise at Edison's new movie studio, the world's first, called the Black Maria.

Despite big plans, a large display of Kinetoscopes never happened at the Chicago World's Fair. Kinetoscope production was delayed partly because Dickson was away for over eleven weeks due to a nervous breakdown. Some historians say one Kinetoscope made it to the fair, while others say it was not ready in time. It's possible people confused it with similar devices shown there.

Work continued on the Kinetoscope project. On October 6, a U.S. copyright was issued for "Edison Kinetoscopic Records." It's not clear which film received this first movie copyright in North America. By early 1894, the project gained new energy. In January, a five-second film starring an Edison technician was shot at the Black Maria. This film, Fred Ott's Sneeze, was made for a magazine article. It was never meant for public showing, but it became one of Edison's most famous films and the first identifiable movie to get a U.S. copyright.

As commercial use approached, on April 1, the movie operation became the Kinetograph Department of the Edison Manufacturing Company. William E. Gilmore was appointed its new general manager. Two weeks later, a major moment for the Kinetoscope arrived.

First Commercial Movie Showings

On April 14, 1894, the Holland Bros. opened a public Kinetoscope parlor in New York City. This was the first commercial movie theater. It had ten machines, each showing a different movie. For 25 cents, a viewer could watch all the films in one row. For 50 cents, they could watch all ten films. The machines were bought from the Kinetoscope Company, which worked with Edison to produce them.

The ten films shown were all shot at the Black Maria and lasted about 15 to 20 seconds each. They had descriptive titles like Barber Shop, Blacksmiths, Highland Dance, and Sandow (featuring a famous strongman). This marked the beginning of a "profound transformation of American life and performance culture," as historian Charles Musser described it.

Paying 25 cents for just a few minutes of entertainment was not cheap. For the same price, you could buy a ticket to a major vaudeville show. However, the Kinetoscope was an instant success. By June 1, the Holland Bros. had parlors in Chicago and San Francisco. Soon, other businesses were opening Kinetoscope parlors across the United States.

Edison's company initially sold each Kinetoscope machine for $250 to distributors. Individual films were priced at $10. In its first eleven months, the Kinetoscope business made over $85,000 in profit for Edison's company.

One new company, the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company, wanted to combine the Kinetoscope's popularity with prizefighting. This led to important changes in movie technology. The Kinetograph camera could only shoot 50 feet of film. At 40 frames per second, this meant a maximum running time of 20 seconds. This was not long enough for a good boxing match. So, the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope were changed to handle filmstrips three times longer.

On June 15, a boxing match was filmed at the Black Maria. Over 750 feet of film were shot at 30 frames per second. This was by far the longest movie made at that time. Weeks later, the film premiered at the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company's parlor in New York. Six expanded Kinetoscope machines each showed a different round of the fight for ten cents. This meant 60 cents to see the whole match. For future fights, they even signed famous boxer James J. Corbett. This was like the first movie star contract. In 1894, 75 films were shot at Edison's studio.

In September, the first Kinetoscope parlor outside the U.S. opened in Argentina. Soon after, the first European parlor opened in Paris. One of the owners gave a film strip to Antoine Lumière, asking for cheaper alternatives to Edison's expensive films. This inspired the Lumière brothers, who went on to create better cameras and the first successful movie projection system. Kinetoscope parlors soon opened in London and Sydney, Australia.

The Kinetoscope spread quickly in Europe because Edison had not protected his patents there. He likely believed his technology relied on foreign inventions, so patent applications would fail. Some older sources incorrectly claimed Edison didn't care about the invention and didn't pay a small fee for international patents. However, Edison spent about $24,000 developing the system and even built a studio just for moviemaking. So, current scholars don't agree with that idea.

Because Edison didn't patent overseas, two Greek businessmen, George Georgiades and George Tragides, took advantage. They hired English inventor Robert W. Paul to make copies of the Kinetoscope. After making their copies, Paul decided to enter the movie business himself. He made many more Kinetoscope copies and, with photographer Birt Acres, developed important innovations in cameras and viewing technology. Meanwhile, Edison's team at the Black Maria was working on combining images with sound.

The Kinetophone: Adding Sound

The Kinetophone was an early attempt by Edison and Dickson to create a sound-film system. A report from October 1893 suggests that a Kinetograph camera with a phonograph was shown at the Chicago World's Fair. This was to demonstrate how sound and images could be recorded together.

The first known movie made as a Kinetophone test was shot in late 1894 or early 1895. It's called the Dickson Experimental Sound Film. It is the only surviving movie with live-recorded sound made for the Kinetophone. In March 1895, Edison offered the Kinetophone for sale. It was a Kinetoscope with a phonograph inside its cabinet. Kinetoscope owners could also buy kits to add the phonograph to their existing machines. The first Kinetophone shows happened in April.

Some sources incorrectly say the picture and sound were synchronized with a belt. However, historians like David Robinson say the Kinetophone "made no attempt at synchronization." Viewers listened through tubes to a phonograph hidden in the cabinet. The phonograph played music or other sounds that were "approximately appropriate." Most films for the Kinetophone were silent. Exhibitors could choose from different musical cylinders that matched the rhythm of the film. For example, three different orchestral pieces were suggested for the film Carmencita.

Even as Edison tried to make the Kinetoscope more popular by adding sound, many people in the field thought that film projection was the next big step.

Edison eventually agreed to explore projection systems. He assigned one of his lab technicians to the Kinetoscope Company to start this work, without telling Dickson. Dickson and Edison's general manager, William Gilmore, had been having problems for months. When Dickson found out about the Kinetoscope Company's move, it was a major reason for his split with Edison in April 1895. The Kinetophone was not very popular. Only 45 machines were built over the next five years. After Dickson left, Edison stopped working on sound movies for a long time.

Projection Takes Over

On January 3, 1895, a British inventor patented a large device to project Kinetoscope images onto a screen. Throughout that year, even as new Kinetoscope exhibits opened around the world, it became clear that the system would lose to projected movies. In its second year, the Kinetoscope's profits dropped by over 95 percent.

The Latham brothers and their father were developing a film projection system. They secretly got help from Dickson while he was still working for Edison. A few weeks after Dickson left Edison, he openly helped with a screening of the Latham group's new Eidoloscope on April 21. Historians say this was the first public film projection in the U.S. On May 20, the world's first commercial movie screenings began in New York. The Eidoloscope showed a boxing match that was about eight minutes long. European inventors, especially the Lumière brothers and the Skladanowsky brothers in Germany, were also developing similar systems.

Another challenge came from a new "peep show" device called the Mutoscope. This was a cheaper, flip-book based viewer that Dickson had also secretly helped create. Before the end of the year, the Mutoscope team developed their own projector, the Biograph. At this point, orders for new Kinetoscopes in North America almost stopped.

By early 1896, Edison focused on promoting a projector technology called the Phantoscope. This was developed by young inventors Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. Raff and Gammon bought the rights to the system, renamed it the Vitascope, and arranged for Edison to be presented as its creator. The Vitascope premiered in New York in April and was very successful. However, it was quickly surpassed by the Lumières' Cinématographe, which arrived in June. The Eidoloscope faced problems with projection and business disagreements. In September 1896, the Mutoscope Company released its projector, the Biograph. It had better funding and image quality than its rivals. By the end of the year, it dominated the North American projection market.

After little more than a year with the Vitascope, Edison's company made a $25,000 profit from film. Edison then started developing his own projection systems, like the Projectoscope and different versions of the Projecting Kinetoscope. He aimed these at semi-professional and amateur customers. Around 1907–08, the Projecting Kinetoscope made up 30 percent of U.S. projector sales. In 1912, Edison introduced the ambitious Home Projecting Kinetoscope. This used a unique film format with three parallel columns of images on one strip. It was not a commercial success. Three years later, Edison's company released its last major new film exhibition technology, a short-lived system called the Super Kinetoscope. After 1897, much of the company's work in movies involved using Kinetoscope-related patents to pressure or block competitors with lawsuits.

Even during early Eidoloscope screenings, exhibitors sometimes played phonographs with sound effects alongside films. Like the Kinetophone, recordings that matched the rhythm were available for march and dance films. Edison did some brief sound-cinema experiments after the success of The Great Train Robbery (1903). But it wasn't until 1908 that he seriously returned to combining sound and images. Edison patented a system that connected a projector and a phonograph using shafts.

In 1913, Edison finally introduced a new Kinetophone. Like his earlier sound-film systems, it used a cylinder phonograph. This was connected to a Projecting Kinetoscope with a belt and pulleys. It was initially praised, but operators had trouble keeping the picture and sound in sync. Also, like other sound-film systems of that time, the Kinetophone had problems with sound being too quiet and not sounding good. Its newness soon wore off. In December 1914, a fire at Edison's complex destroyed all the Kinetophone film and sound masters. After this, the system was abandoned.

Images for kids

See also

- William Friese-Greene

- List of film formats

- Motion Picture Patents Company