King Manor facts for kids

|

King Manor

|

|

|

|

| Location | 150-03 Jamaica Avenue, Jamaica, Queens, New York |

|---|---|

| Area | 11.5 acres (4.7 ha) (park) |

| Built | c. 1730, 1755, 1805–1810 |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001295 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | December 2, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | December 2, 1974 |

King Manor, also known as the Rufus King House, is a special old house in Jamaica, Queens, New York City. It's located at 150th Street and Jamaica Avenue. This two-story house is the main building in Rufus King Park, a large public park that used to be part of the estate of Rufus King. He was a very important person in American history, one of the Founding Fathers.

The house was first built around 1730 and then made bigger in 1755 and again in the early 1800s. It shows off different styles of architecture, like Federal, Georgian, and Greek Revival. King Manor is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. The house, its inside rooms, and the park are all protected as New York City designated landmarks.

The Colgan and Smith families lived in the house in the late 1700s. Rufus King bought the house and the land around it in 1805. He made it into a big 17-room mansion. King lived there until he passed away in 1827. His family stayed in the house until 1896. The house and the remaining land were sold in 1897 to the village of Jamaica and turned into a public park. When Jamaica became part of New York City in 1898, the New York City Parks Department (NYC Parks) took over the property.

The King Manor Association helped fix up the mansion in 1900. It then became a meeting place for different local groups. King Park also changed over the years. There were many ideas to tear down the mansion or use it for other things, but they didn't happen. The house was fixed up after a big fire in 1964. Both the house and park were restored again in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Smaller updates to the house and park happened in the early 2000s.

Today, King Manor has several parts that form an "L" shape. The front of the house is a little uneven, with wooden shingles and a Dutch-style porch. It has a special roof called a gambrel roof. Most of the rooms look like they did when Rufus King made the house bigger in the early 1800s. The first floor has a fancy parlor, a library, and a dining room. The second and third floors have bedrooms.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation owns and takes care of King Manor. The King Manor Association looks after the furniture and items inside. The house has a collection of objects from the 1700s and 1800s. It has also hosted many programs, events, and exhibits over the years. People have talked about both the museum's exhibits and the house's simple design.

Contents

What is King Manor Park Like?

King Manor is located at 150-03 Jamaica Avenue in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens in New York City. It's on the north side of the avenue, between 150th and 153rd Streets.

Rufus King Park Features

The house is the main part of Rufus King Park. This park covers a whole city block and is bounded by Jamaica Avenue, 150th Street, 89th Avenue, and 153rd Street. The park is about 11.5 acres big. It keeps alive a piece of the land that belonged to Rufus King, one of America's Founding Fathers.

The park has many fun things to do. At the north end, you can find a gazebo, a soccer field, and basketball courts. There's also a play area on the eastern side of the park. The south end of Rufus King Park has the mansion itself and public restrooms. About 100 feet north of the mansion, there's also the burial site of a 19th-century enslaved person named Duke.

How the Land Was Used Before

Before Europeans came to Long Island in the 1600s, Native Americans lived there. However, there is no proof that Native Americans settled exactly where the house is now. The park area was between hills called Woody Heights to the north and a trail that later became Jamaica Avenue to the south.

The first building recorded near King Manor was a quartering house in 1666. This building might have been used by the British military. A leathermaker named John Owlffield bought the land in 1664. His family, the Oldfields, later owned property that became part of King Manor.

There might have been other small buildings around King Manor, but their exact locations are not all known. Some might have been used for bathrooms or farming. After the King family moved there in the 1800s, more buildings were added. By 1813, there were two buildings north of the house and another near Grove Street (now 90th Avenue). There was also a stone building to the east that might have been a dairy house or smokehouse. In the 1900s, this building was a milk house connected to the main house.

The House as a Home

Early History (1700s)

We don't know exactly when the oldest part of the house was built. Some research suggests a small cottage was there by 1730. This cottage was likely moved and is now the original kitchen of the current house. Other sources say King Manor dates to 1750. The original part of the house was used as a farmhouse, an inn, and a church rectory in the 1700s.

Two rectors (church leaders) of Grace Episcopal Church lived on the land. Thomas Poyer bought a 53-acre farm in 1726 and lived there until 1732. Thomas Colgan bought Poyer's farm and lived on the estate until 1755. Colgan might have built the western half of what became King Manor. He also likely made Poyer's original building bigger to the north. The farm had a fence and a fruit orchard.

In the mid-1700s, the Colgan house was described as having "eight rooms on a floor, and two good rooms upstairs." The house had windows that looked out over Beaver Pond, which means it probably always faced south. Colgan's widow sold the house in 1759. She passed away in the house in 1776.

The house then went to Colgan's son-in-law, Christopher Smith. Many people thought George Washington slept in the house, but he never did. He did visit a nearby tavern, though. The Colgan and Smith families may have had enslaved people living on the estate. Not much else is known about the Smith family's time in the house. When Christopher Smith died in 1805, he owed money to the estate of politician John Alsop.

Rufus King's Time (1805-1827)

Rufus King, who was John Alsop's son-in-law, was the next owner. King had been a delegate to the Continental Congress and a U.S. Senator. He was also the United States Minister to the United Kingdom from 1796 to 1803. He wanted to move to the countryside by the early 1800s.

King bought Christopher Smith's house and 90 acres of land in 1805 for $12,000. He moved into the house in early 1806 and soon started making it into a mansion. He added a circular walkway, trees, and plants in front of the house. He also planted a row of linden trees behind the house. King used wood from the nearby forest to build a new kitchen in 1806. He also built the eastern part of the main house. The inside rooms were redesigned in the Federal and Georgian styles. By 1810, the dining room was bigger, and the new kitchen was finished. The original cottage was moved behind the main house, creating the "L" shape we see today.

Rufus King was against slavery and paid his workers, which was different from many people in the area. The 1810 United States census shows he had an enslaved woman named Margaret, whom he freed two years later. He reportedly bought her to free her and reunite her with her husband, Moses, who was a free man working for King. There were stories that King buried enslaved people on the grounds, but these were not true. King's servants likely worked in the kitchen area and in the fields and barns. King served as a U.S. senator again from 1813 to 1825 and continued to own the house.

Later King Family Ownership

Rufus King passed away at the mansion on April 29, 1827. He was buried next to his wife in Grace Churchyard. His oldest son, John Alsop King, inherited the manor. John later became a state legislator, a U.S. Representative, and then the governor of New York. The land continued to be a working farm through the mid-1800s. By 1842, several small buildings had been added around the main house. John King died at the mansion in 1867. His widow continued to live there until she passed away.

In the late 1800s, the farm slowly became smaller. Cornelia King, John King's youngest daughter, was the last King family member to live in King Manor. The land around the house was sold off in the 1880s. Cornelia lived at the estate until she died in 1896.

After Cornelia's death, her brother John A. King was offered a lot of money for the house but said no. The area was growing fast, but many old estates like King Manor were still standing. Local newspapers suggested selling the King estate to the village of Jamaica and turning it into a public park. They said the house was "famous and interesting from its historical associations."

King Manor as a Park and Museum

Becoming a Park

By 1897, people in Jamaica wanted to buy the rest of the King estate. John A. King offered the land to the village of Jamaica for $50,000, which was a good deal. Residents voted to buy the land on June 29, 1897. The village bought the land on July 9 and opened it to the public. They also hired a police officer to live in the house as a caretaker. The park was officially renamed Jamaica Park in October 1897.

Jamaica became part of New York City in 1898, and the New York City Parks Department (NYC Parks) took over the house and land. The park was renamed King Park. In 1898, there were ideas to use the mansion as offices for city groups, like the police or the Board of Education. However, by 1899, the house was only lived in by a janitor. City officials planned to restore the mansion and its grounds.

Clubhouse and Early 1900s

In early 1900, local women, led by Mary E. Craigie, wanted to turn King's mansion into a clubhouse for local groups. The King Manor Association (KMA) was formed in February 1900. Groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and the Jamaica Women's Club planned to fix up the first-floor rooms. The KMA signed a lease for the house in June and started planning to make it a headquarters for local clubs. They asked for "furniture, pictures, books, and what not" to furnish the house. They also planned to open the house to the public one day a week.

The first social meeting in the house happened in October 1900. The renovated first floor had a green-and-white hallway, a tan-and-white drawing room, and a dark-red library. The dining room was used as a meeting room. Many civic clubs moved into the mansion. The KMA received its official paperwork in December 1900 and had over 200 members. A caretaker also lived in the back of the house. Water and sewer pipes were installed starting in 1902. The KMA also wanted to restore the inside of the mansion, the roof, and the porches, and repaint the outside. This work was finished by 1903.

New York City thought about building a library at King Manor in 1902, but local people didn't want that. The Long Island Society of the Daughters of the Revolution restored the house's parlor in 1903. In 1904, the KMA agreed to take care of the house's inside and furnishings, while NYC Parks would maintain the park. The house was open to the public on Mondays and had many visitors each year. There were also plans to move Queens' borough hall to King Park in the late 1900s.

1910s and 1920s

By 1911, there was a plan to turn the house into a regional office for NYC Parks, but the KMA protested, and the office was moved. The KMA started restoring the house that same year. A fence was put around King Park, and NYC Parks set aside money for a new bathroom in the park. NYC Parks cleaned up the grounds in 1913. The KMA started letting visitors into the house three days a week in late 1914. A bandstand and restroom were built in the park in 1915. More clubs used the house in the late 1910s.

Two cedar trees from former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt's home were planted in front of the house in 1919. In 1920, there was a proposal to move the Queens Borough Public Library's Jamaica branch into King Manor. Many groups, including the DAR, were against this idea. The library plan was dropped in 1921. When a children's shelter was suggested for the house in 1921, civic groups strongly objected.

Free concerts were held in King Park throughout the 1920s and were very popular. One of King Manor's rooms was re-furnished for the Jamaica Village Society in 1923 or 1924. This room was used to show old documents and artifacts from 19th-century Jamaica. King Manor was one of the few old mansions left in Jamaica by the 1920s.

1930s to 1970s

In 1930, there was a proposal for a civic center in King Park, with four 10-story government buildings around King Manor. The KMA strongly opposed this plan, and it was delayed. NYC Parks started installing electricity, heating, and plumbing in the house in 1931. A new bathroom was finished in 1935. Another proposal for a civic center in the park was dismissed in 1936. At that time, the park had a cannon, flagpole, bandstand, and the new comfort station, besides the mansion.

The mansion was renovated more in the early 1940s as part of a program to restore historical sites. The house had 1,000 visitors every month in 1943. It remained open three days a week in the 1950s and 1960s. A playground and basketball court were built east of King Manor in 1957.

The house was badly damaged by a fire in March 1964, likely caused by bad wiring. Two rooms were destroyed, and there was smoke and water damage. The restoration of the mansion was finished in 1966, paid for by donations.

In 1973, some teenagers set fire to the house's porch, but people nearby saw it before major damage happened. The house was open on Thursdays in the late 1970s. The KMA had restored more of the house's inside by then. The park was popular with students and visitors to the nearby courthouse. There were also some safety issues in the park, which the police worked to address. In 1979, the King Manor Association raised money for a special fund for the mansion.

1980s and 1990s

Architects checked the house in 1980 and found it was mostly in good shape, though some parts of the outside were wearing down. Women's groups asked the city to renovate the house. The house and park also had some problems with damage and other issues. City Council member Sheldon S. Leffler asked for money for the house's renovation in 1983. The city provided funds for design and renovation in 1984. The KMA also got money for new furnishings and exhibits. Archeologists found artifacts in the house and park during a dig in 1985.

In March 1987, New York City started renovating King Manor. This project included new systems for heating, electricity, and security. It also involved repainting and restoring decorations. The mansion's rooms were repainted their original colors. The park also got a new bandstand and bathroom. The house was closed for most of this time, except for monthly tours.

King Manor became one of the first members of the Historic House Trust in 1989. Roy Fox became the house's caretaker in 1989 and lived on the third floor. He and his wife gave unofficial tours. In early 1990, work began on the park itself, and researchers started archeological studies. The park work included moving the bandstand and adding new benches, paths, and fences.

City officials officially reopened the house on June 21, 1994. The King Manor Museum cost $2 million to renovate, and the park cost $4 million. Roy Fox, the caretaker, often gave talks and performances. The number of visitors to King Manor grew a lot between 1995 and 1999. The city also spent money on a fence around the park, which was finished in 1997.

2000s to Today

A $300,000 renovation was announced in May 2002. This project included new doors, windows, and repairs to the wooden porch. The outside was repainted, and the air conditioning, lighting, and fire detectors were updated. The museum stayed open during the renovation. By 2004, researchers had found 4,000 artifacts in the park over the past ten years. In 2005, the house was added to the state's Underground Railroad Heritage Trail because the Kings were against slavery.

King Manor and Park were updated again as part of a $1.7 million project finished in 2008. This project included drainage improvements, drinking fountains, a turf field, and a concert space in the park. New trees and a driveway were added at the mansion. In 2009, Queens borough president Helen Marshall gave $200,000 for a restoration of the house's chimney. Another $2.2 million renovation of King Park was announced in 2015. NYC Parks announced new entrances for the park in 2017 and replaced the mansion's roof in 2018. A new space for temporary exhibits opened in December 2019.

The mansion closed temporarily in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Roy Fox, the caretaker for three decades, continued to maintain the property. A Parks Enforcement Patrol substation in the park was finished in 2021, and the house's heating and cooling system was fixed that year. However, King Manor officials said in 2023 that the house needed more care. Its outside hadn't been repainted in twenty years, and the dining room was partly closed because plaster was falling. Museum officials also said that the Wi-Fi stopped working in late 2020 and hadn't been fixed, which made it hard to host events.

What Does King Manor Look Like?

We don't know who designed King Manor. The house's design has parts of the Federal, Georgian, and Greek Revival styles. King Manor is made up of several sections that form an "L" shape. The main house is in the middle, and the kitchen is in a section that extends north from the eastern part of the main house.

Outside the House

The western part of the main house was built in the mid-1700s and has two stories with a half-story attic. The eastern part was added during the Kings' renovation in the 1800s. The outside is mostly covered with white wooden shingles. The two sections look similar, but the eastern part has wider architectural details, making the front a little uneven. Both sections have a gambrel roof with two chimneys.

The main entrance is through a porch on the south side. This porch has columns with grooves in the Doric order style. Inside the porch is a Dutch door, with windows on either side and a window above the door. The porch has a decorative cornice with dentils (small block-like shapes). There's also a Palladian window right above the porch.

The back section, which extends from the original house, might be the oldest part of King Manor. It includes the Colgan and Smith families' kitchen, plus another kitchen and a lean-to added by the Kings. This back section has one- and two-story parts, topped with gable roofs and brick chimneys. The southern part of this section, next to the main house, is two stories tall and has a porch with columns.

Inside the House

The inside rooms mostly look like they did when Rufus King renovated and expanded the house in the early 1800s. After King finished his renovations, King Manor had 17 rooms, including a drawing room and family room. By the 1990s, it had 29 rooms. The rooms had fancy marble fireplaces.

First Floor

The first floor generally has a balanced layout, with a central hallway dividing it. However, the main entrance door is not exactly in the middle of the hallway. The main hallway is about 12 by 40 feet. Its walls are made of plaster, with a baseboard and a chair rail on the lower half. There are four doorways leading off the hallway. A staircase to the second floor is at the back of the eastern wall.

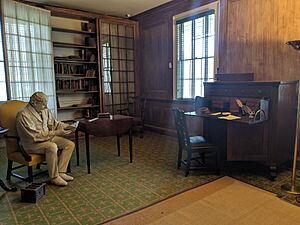

The western half of the first floor has a parlor and a library (also called the family room). Both rooms are 24 feet wide. The parlor is 16 feet deep, and the library is 22 feet deep. The parlor, in the southwest corner, has a gray-and-white marble fireplace mantel added in the late 1820s. The library has three built-in bookcases that came from England. When King lived there, the library had 5,000 books, mostly about the Americas. The library's fireplace has white-and-blue Dutch tiles.

In the southeast corner of the first floor is the dining room, which is 22 by 34 feet. It has a Federal-style fireplace and a curved wall at one end. The fireplace is surrounded by pilasters (flat columns) that hold up a mantelpiece shelf. The room has gold-painted walls, red window curtains, and a black-and-white floor covering. Behind the dining room and stairway are the kitchens, which were moved from where the dining room is now in the 1800s. A serving pantry connects the kitchens and the dining room.

Second Floor

The second floor generally has a similar layout to the first floor. In 1898, it was described as having four large rooms and three smaller ones. The main house's second floor has a sitting room, bedrooms, and a children's playroom. The staircase from the first floor opens into a wide central hall on the second floor. At the eastern end, a short set of steps leads down to the former children's playroom, which was also used by servants.

To the southwest is a sitting room, which still has most of its 18th-century details. This room has a marble fireplace frame and a decorative mantel. It also has a door, baseboard, chair rail, and cornice, similar to the first-floor parlor. This room was once used by the Queens Borough Musical Society.

The bedroom in the northwest corner, which Rufus King used, has baseboards, chair rails, and cornices on the walls. There's a fireplace on its south wall, surrounded by wooden panels. This room was also used as an assembly room by the Queens Borough Musical Society. Another bedroom in the northeast corner had small closets and lots of furniture in the early 1900s.

Other Floors

The third floor had smaller rooms than the floors below. In 1898, it was described as having five rooms and a large attic. The third floor is where the caretaker's apartment is, with two bedrooms under the roof. Some of the upper-story rooms are usually closed to the public today. There is also a cellar under the entire house. The wooden parts of the cellar ceiling and floor were made by hand.

How King Manor Operates

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation owns and maintains King Manor. The King Manor Association supervises the furniture and items inside. The KMA was formed in 1900 to care for the house and collect historical items. The museum became a member of the Historic House Trust in 1989.

What's in the Collection?

Before the museum closed for renovation in 1987, its collection mostly included furniture and objects from the 1700s and 1800s. When the house opened to the public in 1900, it had a piano, a mahogany bed, an old desk, and a rare painting of the Washington family. The kitchen had a stove and large brick ovens. The KMA encouraged people to donate or lend old items. Over the years, they received artwork, furniture, carpets, and other decorative items. They also received items that belonged to the Kings, like a letter from John Alsop King and Rufus King's silverware.

After the renovations in the 1980s and 1990s, copies of original furnishings were put in, including the carpet in the parlor and the 5,000 books in the library. The house also has original items, like an 18th-century piano from England and an old leather sofa that belonged to Rufus King. The library has a plaster statue of Rufus King.

Programs and Events

The house started hosting club meetings and events in October 1900. These events included anniversary celebrations, fundraisers, and plays. In the mid-1900s, the house was also used for things like gift-wrapping lessons and art competitions. Tours of historical sites in Queens sometimes stopped at the house. In the late 1900s, the house and park often hosted cultural events, like celebrations of King's birthday and historic-house tours. In the 2000s, events included naturalization ceremonies, poetry readings, and holiday concerts.

The museum offered tours in both English and Spanish by the late 1900s. In 2001, the King Manor Museum started an archeology program with local public schools. As of 2025, the museum's educational programs include classes on the Revolutionary War and King's efforts against slavery. Guided tours are available from February to December.

Exhibits

In King Manor's early years as a museum, one room on the second floor was used to display furniture and old items. The house hosted exhibits of antiques, as well as textile and metal exhibitions. By the mid-1900s, exhibits included showcases of family treasures and the house's history. A news article from 1957 called the house a "treasure-trove of 18th century lore."

To attract visitors after the 1990s renovation, the museum put up signs in two languages and hosted events in both English and Spanish. The parlor and other first-floor rooms were used for meetings. The parlor showed a video about King Manor's history. Visitors could explore many rooms, which were not roped off like in some other museums. In the 2000s, the King Manor Museum has continued to show exhibits about the King family. Since 2019, the second floor has been used for temporary multimedia exhibits. Some of these temporary exhibits are also available to view online after they are displayed.

What People Think of King Manor

In the late 1800s, newspapers described the house's old architecture and "charming" furniture. One newspaper said the house was "famous and interesting from its historical associations." Another said it was "destitute of architectural beauty" but very solid. In 1900, the Standard Union said the house "bears comparatively few traces of the many winters it has weathered" because it was built by hand. In 1903, the New York Times said the house was as interesting as the Van Cortlandt House for history and colonial items.

Later on, people still liked it. In 1997, a critic for Newsday called the house "a rewarding destination for families curious about Long Island's prestigious past." Another critic wrote in 1998 that it was "an eminently user-friendly attraction run by a high-spirited staff." Mimi Sheraton of the Times said in 2001 that King Manor was "the most rewarding historic site I visited in Queens." However, the Daily News wrote in 2009 that the house was not a top tourist spot because Rufus King's roles as a senator and diplomat were not widely known.

King Manor has also appeared in books and TV shows. It was in a 1950s guidebook of historical buildings in New York City. The house was shown in a mural at the New York City Subway's 111th Street station in 1977. It was also featured in a TV series in 1996.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) decided to make King Manor a city landmark in 1966. This included the outside of the building and the park grounds. The house was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974. The LPC also made parts of the first- and second-floor interiors a landmark in March 1976. The Queens Chamber of Commerce gave the mansion its Historic Structure Award in the 1980s.

See also

In Spanish: Mansión King para niños

In Spanish: Mansión King para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |