Lajos Kassák facts for kids

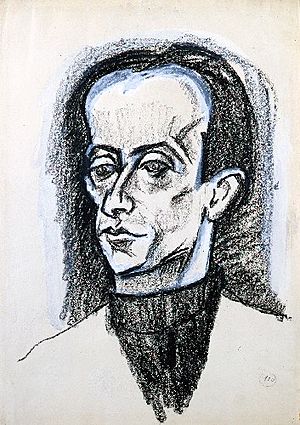

Lajos Kassák (born March 21, 1887 – died July 22, 1967) was a talented Hungarian artist. He was a poet, writer, painter, and editor. He was also a thinker who helped shape the avant-garde art movement. Kassák was one of the first writers from a working-class background in Hungarian literature.

He taught himself many things and became a writer within the socialist movement. He started important journals that influenced Budapest's intellectual scene in the early 1900s. Kassák used ideas from different art styles like expressionism, futurism, and dadaism. People saw him as a gifted artist who used his art to support social causes. He helped lead the way for new art in Hungary.

For a long time, Kassák's work was not fully recognized. This was because his political and artistic activities were often hidden by the government of the time. He started as a locksmith, then became a political activist, writer, editor, and painter. His artistic and political work began in the 1910s. In 1920, he had to leave Hungary and go to Vienna because the Hungarian government was against thinkers like him.

This difficult time actually helped his writing career. He held art shows, readings, and edited journals. These ideas later returned to Hungary, where a quiet movement for social change was growing. After six years, Kassák came back to Hungary. He started more literary projects, including the Munka Circle and its journal. This group helped bring back a united avant-garde art movement focused on social and political ideas.

The government often opposed Kassák's groups and publications. But many of them still did well. For example, the Munka group was banned, but it only ended because of problems within the group itself. Kassák was also involved in politics. He led the Arts Council and edited progressive journals. He even became a member of Parliament for the Social Democratic Party. His political roles affected how his writing was received after the Communist government took power after World War II. He was forced to live a quiet life at home. It wasn't until 1956 that his reputation as a writer grew, though his full artistic legacy was still not completely appreciated.

Kassák used many different ways to share his social messages. He wrote books, painted a lot, supported early social photography in Hungary, and worked with music. His partner, Jolán Simon, led a speaking choir that performed at Munka Circle meetings. Kassák also explored film and dance. He helped bring Russian art into the Hungarian art scene. Today, Kassák's works are getting more attention, with many of his books being reprinted. In 1967, on his 80th birthday, he received a state medal for his political and artistic efforts. He passed away on July 22, 1967, and was honored by his friends and colleagues.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Kassák was born in Érsekújvár, Austria-Hungary (now Nové Zámky, Slovakia). His father was a pharmacy assistant, and his mother was a laundress. His parents wanted him to go to college, but Kassák decided to stop school. He became a locksmith's assistant. His sister, Erzsi Újvári, later married Sándor Barta.

After leaving school in 1900, Kassák trained for four years. Then he moved to Budapest to work in a factory. From 1904 to 1908, he joined trade union struggles. He helped organize strikes and protests and joined the Hungarian Social Democratic Party. Because of this, he lost his job and was not allowed to work in factories anymore. Before this, one of his poems was published. He also met Jolán Simon, who would later become his wife.

Kassák learned a lot about the social and political problems of his time by himself. This made him even more determined to be an activist. Because of his difficult situation, Kassák walked to Paris. He entered the country secretly after being sent away from Belgium and Germany. In Paris, he visited museums, wrote, and lived like a traveler.

When he returned to Budapest in 1910, Kassák started getting involved in political and literary causes. His poems and short stories were published in newspapers and socialist magazines. In 1915, Kassák began publishing his own journal, A Tett. He gathered writers and artists who shared his views. These thinkers became critics of the war, speaking out against it.

His Career and Journals

In 1904, Kassák moved to Budapest and worked in a factory. He joined the labor union movement and organized strikes. He was fired several times for this.

In 1907, he traveled to Paris on foot, without money. Paris was a magnet for artists and thinkers from Eastern Europe. He was sent back to Hungary in 1910. He later wrote about these travels in his autobiography, Egy ember élete (A Man's Life).

Even without much formal education, Kassák worked hard to publish his writings. His first poem came out in 1908. His first collection of short stories, Életsiratás, was published in 1912. In 1915, he published his first poetry collection, Éposz Wagner maszkjában (Epic in the Mask of Wagner). That same year, he started his first journal, A Tett (The Action). It was quickly stopped by the government for being "pacifist," meaning it was against war. He supported a group of painters called The Eight in his journals. He then started Ma (Today) in Budapest and later published it from Vienna.

During the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919, he joined a special Writers Directorate. He had strong disagreements with the republic's leader, Béla Kun. Kassák moved away from Bolshevism but always remained a leftist. He believed that being a socially responsible person and an artist were the same thing. His art was part of his identity as a "socialist man." After the Hungarian Soviet Republic fell, he moved to Vienna. There, he continued publishing his second journal, MA ("Today," also meaning "Hungarian Activism"). He also published an art book called Buch neuer Künstler. László Moholy-Nagy helped him gather materials for it from Berlin.

In 1926, Kassák returned to Hungary. He kept editing and publishing journals like Munka (Work) (1927–1938) and Dokumentum (Document) (1927). Both were independent leftist avant-garde journals.

His autobiography, Egy ember élete (A Man's Life), was published in parts in the Hungarian literary journal Nyugat from 1923 to 1937. After it came out as a book, he faced problems because of chapters about the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

He regularly wrote for leftist newspapers. From 1945 to 1947, he edited the journal Kortárs (Contemporary), which was later banned. In 1947, he returned to political duties as the communists took over the Hungarian government. He became the head of the Social Democratic Party's Art Commission. In 1948, he became a Member of Parliament. A year later, he had to leave Parliament and eventually retire due to political changes.

In 1953, Kassák criticized the Party's cultural policies and was removed from the party. Because of this, he could not publish for years. In 1956, he was elected to lead the Writers Association, an important group at the time. From 1957, the government's censorship made it very hard for him to publish, travel, or show his art. But even in silence, he influenced many artists in Hungary and around the world. He passed away in Budapest on July 22, 1967.

His Artistic Work

Kassák is seen as a key figure in Hungarian Avant-garde art. He was one of the first artists from a working-class background. His ideas about avant-garde movements shaped art in the region. His journals Ma ("Today") and A Tett ("The Deed") were very popular. He was greatly influenced by the international constructivist movement. He wrote several manifestos, which are public statements of his beliefs, such as Képarchitektúra ("Image Architecture", 1922) and A konstruktivizmusról ("On Constructivism", 1922).

Because he was part of many styles, art historians often call him an "Activist." This label shows his art was focused on social issues. He believed art should be useful and have a social impact. He thought modern people should use art to create a world where everyone is equal.

His works included concrete poetry, designs, novels, and paintings. They were influenced by Expressionism, Dadaism, Futurism, Surrealism, and Constructivist ideas.

A Tett Journal

From November 1915 to 1916, during World War I, Kassák started his first journal, A Tett (The Action). This journal was an artistic protest against the war. It was named after a German anti-war journal called Die Aktion. Kassák had always spoken out against war in his poems. For A Tett, he worked with artists from countries involved in WWI. Their goal was to criticize the war in Hungary, France, Germany, and all of Europe.

Kassák was an "anti-war intellectual." His strong views against war were clearly shown in A Tett. The journal aimed to criticize the "war culture" and the idea of blaming "enemy camps." It welcomed the political views of international writers, not just as observers but as active participants. This angered local critics. The journal explored themes like criticizing pro-war thinkers and events, showing that war heroes were not always perfect, and speaking out against targeting supposed enemies.

A Tett lasted for almost a year. But on October 2, 1916, the government banned it. They said some articles were against the war. The fact that the second issue included works from "enemy camps" like Russia, Belgium, and Britain was seen as a danger to Hungary's war efforts. Still, A Tett sent an important message to the world when it was truly needed.

MA in Budapest

This was Kassák's second journal. He started it with his group of artist-activists. Kassák said the journal focused on fine arts and music, not just literature, to avoid government control. The journal, meaning Today, aimed for strong activism through art and visual messages. It criticized political problems, especially the government limiting artistic freedom in the 1910s.

To achieve this, MA changed a lot between November 1916 and July 1919. It published 35 issues before being banned. Its subtitle changed from "periodical of literature and arts" to "activist periodical," then "periodical of activist art and society." The journal also worked with theaters and a popular publishing house, which helped it reach more people and gain an artistic image.

MA even published important books and postcard series featuring works by Hungarian artists like Nemes-Lampérth József, Lajos Tihanyi, and Kassák's brother-in-law Béla Uitz. The people involved with MA also organized literary events and art shows. These events helped bring together the scattered avant-garde artists in Eastern Europe. The MA circle became a movement itself, helping many artists become famous, like János Mattis-Teutsch. All these efforts made Kassák known as a remarkable European avant-garde artist.

Even though MA was presented as art-focused, it also addressed important political events. It openly called for artistic independence. Four special issues discussed the democratic revolution of 1918 and the rise of the Communist Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919.

Before MA was banned, Kassák had a public disagreement with Béla Kun, the leader of the Hungarian commune. Kassák was part of the Writer's Directory but left after this clash. His arguments in this debate were published in MA as "Letter to Béla Kun, in the Name of Art." After the Republic of Councils fell, Kassák moved to Vienna in 1920 to avoid being arrested.

MA in Vienna

In Vienna, Kassák changed MA even more. He updated its design and content and gave it a new focus on international ideas. By making the journal internationally focused, Kassák could feature many artists from other European countries. He also worked with other international publications, sharing ideas and distributing his journal.

Because of this, constructivism, a modern art style, became very important in the new MA. This attracted many modern artists like Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, El Lissitzky, and Hans Jean Arp. Kassák formed lasting friendships with many of them. The new approach of MA helped it last longer than it did in Hungary. The journal MA was a groundbreaking Hungarian avant-garde publication that truly showed revolutionary activism in 20th-century Hungary. Its activities were as important as the Hungarian journal Nyugat and other avant-garde journals like Zenit, which were published in other Eastern European countries. After being very popular for several years, MA's publication slowed down and stopped when Kassák returned to Hungary.

Dokumentum in Budapest

Another journal Kassák started was Dokumentum. It launched when he returned to Hungary in the autumn of 1926. Even though it didn't last long, it stood out and gained international attention. What made it special was that it was multilingual, with articles in Hungarian, French, and German. It aimed to reach a global audience. However, its new avant-garde ideas were not popular with many people, and it stopped publishing after about six months.

Munka Journal

This journal, also founded by Kassák, was different from his others. It had a stronger social focus. It was meant to be an educational platform for workers, helping them share his vision for the political future. The word Munka itself means "Work."

Munka became more than just a journal; it became a movement. It attracted workers and students to a "Circle" that built strong bonds among its members. The Kultúrstúdió (Cultural Studio) was a place for both activism and art. It held many events that entertained, showed experimental art, and helped change the political views of attendees. The number of members grew because Munka was an open group.

This welcoming group had different choirs, including a speaking choir led by Kassák's partner, Jolán Simon. There was also a modern-music choir and a folk-song choir. A painting group, mostly students from the Academy of Fine Arts, was also part of it. The group organized hiking trips and summer bathing at the beach. They also had adventurous camping trips to places like Horány. Most participants were workers of all kinds, including civil servants, office workers, craftspeople, and small business owners.

The journal focused on cultural and social issues affecting Hungary. It was also made affordable, so it became very popular and grew quickly. It lasted from 1928 to 1939. Then it faced opposition and censorship from the government. It finally ended because of a government order and internal conflicts within the group. Besides his own projects, Kassák also wrote for other papers like Népszava and Szocializmus.

As a Writer

Kassák was a very successful writer. He wrote and published for many decades and received literary praise. One of his most important works is his autobiography, Life of a Man, which he started writing when he was 36. Kassák wrote many avant-garde poems and novels. His novels, which focused on social issues, helped spread the ideas of his movement.

In his early years, when he was in exile and isolated, Kassák experimented with his poetry. He wrote free-verse poems that explored many different themes. In his later years, Kassák wrote and published many poems about his personal struggles, his surroundings, his past, and his inner thoughts.

Besides his fictional works, Kassák wrote many political articles. He spoke out against any political or racial injustice. For example, he published articles against the "third anti-Semitic law" during World War II. Because of his writing achievements, Kassák held important positions in several literary publications. After WWII, he edited Új Idők (New Times) and was the vice-chairman of the Arts Council. He also edited the periodical Alkotás and Kortárs while he was a member of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party. He was also a key leader in the Journalists Association, the Hungarian Writers’ Association, and co-president of the PEN Club.

In 1948, Alkotás and Kortárs stopped publishing due to increasing political oppression. In 1953, Kassák was sidelined within the Hungarian Writer's Association after he disagreed with its members about the cultural policies of the Hungarian Democratic Party.

This made it hard for him to find publishers, and his creative work was held back for a long time. However, he was still able to publish and show his later poems and paintings internationally. His works were displayed in galleries and museums in Paris, Vienna, Israel, and Switzerland. Despite the government trying to limit his work, Kassák was recognized nationally as a writer and poet in Hungary. In 1965, he even received the Kossuth Award for his poetry.

As a Visual Artist

When he was younger, Kassák was not widely known as an avant-garde artist, even though he was praised as a writer. It was only in his later years, when Eastern European avant-garde art gained international recognition, that Kassák's artworks began to be shown in Western Europe. Some of his pieces even became popular with art lovers there.

Most people know Kassák as a brilliant writer who started many social and critical journals. But he was also a painter with interesting artworks. Kassák explored visual art because he wanted to share his messages through any available means. He knew that visual language was powerful for showing social themes. He used constructivist aesthetics, painting shapes and colors to create meaning and making manifestos out of lines and forms.

One of his famous artworks is Dynamic Construction, created between 1922 and 1924. Besides constructivist painting, Kassák was very interested in photography, especially social photography. He helped organize a big social photography exhibition, which was followed by a book called From Our Lives. His interest in photography led him to create photomontages. In these, he combined several pictures around a theme to visually represent the social and cultural causes important to the workers in the Munka Circle.

Kassák pioneered unique art forms that combined different media. For example, he was known for his image-poems, which he wrote between 1920 and 1929. Kassák not only designed the covers of his many books but also worked with others to design the artworks on the covers of his edited journals. These covers were carefully made to show the mood of each issue. He and his contributors carefully designed these covers to reflect the issue's theme, showing how he skillfully combined words and images.

Besides painting, he also developed theories about modern art and constructivism. The main idea of constructivism was that painting shapes and colors should create a "constructed space." To do this, artists considered movement and how things pull against gravity when creating art. Because of his contributions to constructivist theories, Kassák called himself a theoretician. He took part in discussions about international and Hungarian modern art. He lived up to this title by experimenting with transferring constructivist patterns from objects like glass to images. He also developed his own prints using linocuts, a technique also used by László Moholy-Nagy. To share his constructivist vision, Kassák published a shorter German version of a manifesto in the 1922 Volume 1 edition of the MA journal, titled ‘Bildarchitectur’. His involvement in modern art movements made him an important figure in his time.

Involvement in Dadaism

Even in his writing, Kassák was influenced by the Dadaist style. His journal MA was said to "show Dadaist features... which gives it great strength and a positive power... [and helped] create a new atmosphere." Between 1920 and 1929, Kassák wrote a collection of 100 numbered poems. Many of them, like Poem 8 and Poem 32, had "graphic displays of letters and lines," "free play with words," and a sense of the absurd. It was even said that, later in life, Kassák's avant-garde activism began to turn into a unique kind of Dadaism.

Képarchitektúra

Képarchitektúra, or Image Architecture, was first described in a pamphlet by Kassák in late 1921. This important statement was reprinted in MA 7, no. 4 (March 1922), pages 52–54.

Kassák and Hungarian Avant-garde Art

Avant-garde art in Hungary grew as an independent artistic expression with political ideas, especially during the rise of modernism in the 20th century. In this important international art scene, Kassák stands out. His active involvement in avant-garde art has gained much attention recently. In fact, the Hungarian avant-garde scene largely centered around him. Writer Bosko Tokin called him "the strongest expression of the movement [as his] poetry carried the stamp of a revolutionary experience and of hope in the human race, in the ideal of the human community."

Besides his poetry, Kassák's avant-garde work was highlighted by his founding of the "main Hungarian activist journal Ma [which] spanned several years and was very productive." It is widely accepted that the history of Hungarian avant-garde art and its visual developments is linked to "the four avant-garde journals edited by Kassák between 1915 and 1927 – A Tett (The Action), Ma (Today), 2×2, Dokumentum (Document)." These journals were important for shaping Hungarian avant-garde art. They served as ways to research, present, interpret, and discuss the issues of the time.

When praising Kassák's role as the "heart and soul" of the avant-garde movement in Hungary, his activities were highlighted. He was seen as "a poet, novelist, painter, author of image-poems of unusual intensity and decisiveness. His thought is always modern. His spirit, thoughts, impulsiveness and style possess the unusually daring “tournures” (contours)."

Kassák also worked with other writers and artists in Europe. Together, they created a strong connection of avant-garde activities that covered many art forms: poetry, literary criticism, painting, and music. Like in former Yugoslav countries and other ex-Socialist states, avant-garde art was more about individual cultural efforts than national trends. Amidst these individual artistic works, the avant-garde practiced by Kassák and others was clearly defined by a strong desire to "find [humanistic], adequate means of expressing one’s inner world."

Personal Life

Simon Jolán

Kassák's first wife, Jolán Simon, is not often talked about, but she was very important to his success as an artist and political activist. She was married once before, at age 17, to János Pál Nagy, a carpenter's assistant, with whom she had three children. Jolán met Kassák after leaving that marriage, at an event organized by the Újpest Worker's Home. At the time, she worked at the United Bulb, an electrical company. She later went to acting school and became a professional actress.

Jolán Simon was a strong support for Kassák when he was not yet recognized as a writer and artist. She supported his writings and publications while working as an actress. She moved with him to Vienna in 1920 and helped manage his publishing of A Tett and MA. When she returned to Budapest with Kassák, she led the speaking choir that often performed at the meetings of the Munka (Work Circle) movement members. Other close people who helped his success as an avant-garde artist, activist, and editor included his sister and brother-in-law. In 1940, Kassák met Klára Kárpáti, whom he later married.

Legacy

- The Lajos Kassák Museum, in Óbuda, northern Budapest, is located near where he last lived. It has about 20,000 items related to his life and work.

Quotations

- "The father of every good work is discontent, and its mother is diligence."

See also

In Spanish: Lajos Kassák para niños

In Spanish: Lajos Kassák para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |