Lloyd Fredendall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lloyd Fredendall

|

|

|---|---|

Fredendall as Lieutenant General

|

|

| Born | December 28, 1883 Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, U.S. |

| Died | October 4, 1963 (aged 79) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Buried |

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1907–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | 57th Infantry Regiment 4th Infantry Division XI Corps II Corps Second Army Central Defense Command |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal Philippine Campaign Medal Mexican Border Service Medal World War I Victory Medal American Defense Service Medal American Campaign Medal European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal World War II Victory Medal |

| Spouse(s) | Crystal Daphne Chant (m. 1909-1963, his death) |

| Children | 2 |

Lieutenant General Lloyd Ralston Fredendall (born December 28, 1883 – died October 4, 1963) was an important officer in the United States Army during World War II. He is mostly known for his leadership during the Battle of Kasserine Pass. This battle was one of America's toughest defeats in World War II, and because of it, he was removed from his command.

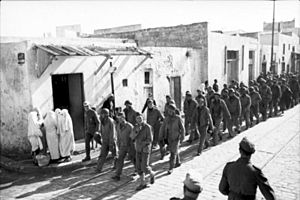

He led the Central Task Force during the landings in North Africa, known as Operation Torch. He also commanded the II Corps at the start of the Tunisian Campaign. In February 1943, his forces were defeated by German forces led by Erwin Rommel and Hans-Jürgen von Arnim at the Battle of Kasserine Pass. After this defeat, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the top Allied commander in North Africa, replaced Fredendall with George S. Patton. Even after being removed from command, Fredendall was promoted to lieutenant general in June 1943 and was seen as a hero in the United States.

Early Life and Army Career

Lloyd Ralston Fredendall was born on December 28, 1883, at Fort D. A. Russell in Cheyenne, Wyoming. His father, Ira Livingston Fredendall, was also in the United States Army. Ira later became a sheriff and then rejoined the army during the Spanish–American War. He retired as a lieutenant colonel.

Because of his father's connections, Fredendall was able to apply to the United States Military Academy (USMA), also known as West Point. However, he struggled with math and was dismissed after just one semester. He tried again the next year but dropped out again. Instead, he went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a year. In 1906, he took an exam to become an officer and scored the highest among 70 people. On February 13, 1907, he became a second lieutenant in the Infantry Branch of the U.S. Army.

After serving in the Philippines and other places, Fredendall went to the Western Front in France in August 1917 during World War I. He worked as an instructor and led training centers. He was known as a great teacher and organizer. He finished the war as a temporary lieutenant colonel.

Between the World Wars

After World War I ended in 1918, Fredendall had many different jobs in the army. He was both a student and a teacher at the U.S. Army Infantry School. He also graduated from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff School and the U.S. Army War College. These experiences helped him make important connections that would help his career later on.

In December 1939, as World War II began (though the U.S. was not yet involved), Fredendall was promoted to brigadier general. In October 1940, he became a major general and commanded the 4th Infantry Division.

World War II Service

Fredendall's career grew during World War II thanks to George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, and Lesley J. McNair, a friend and commander of Army Ground Forces. Marshall thought highly of Fredendall and suggested him to Dwight D. Eisenhower for a big command in the Allied invasion of North Africa, called Operation Torch.

Marshall liked Fredendall's confident attitude, calling him "one of the best." Eisenhower initially had doubts but chose Fredendall to lead the Central Task Force, which had 39,000 soldiers, in Operation Torch. After the invasion, Eisenhower even said he was glad Marshall had pushed for Fredendall. However, Eisenhower later changed his mind about Fredendall's abilities.

Tunisia, Oran, and Kasserine Pass

After the Torch landings, Fredendall became the military governor in Oran. His orders from his fancy hotel headquarters were sometimes mocked by his soldiers, who were living in tough conditions.

Fredendall was put in charge of the U.S. II Corps for its advance into Tunisia against German forces. He served under the British First Army, whose commander, Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson, thought Fredendall was not good at his job even before the Battle of Kasserine Pass. Fredendall often used strange slang in his orders, like calling infantry "walking boys" and artillery "popguns." Instead of using standard map coordinates, he made up confusing codes like "the place that begins with C." This made it hard for his officers to understand his commands, wasting valuable time.

During the advance into Tunisia, Fredendall had engineers build a large, strong headquarters bunker about 70 miles (110 km) behind the front lines. It took three weeks to build this bunker out of solid rock. He also ordered a special bulletproof car like Eisenhower's. Omar Bradley, who was a brigadier general at the time, called Fredendall's headquarters "an embarrassment to every American soldier." Eisenhower himself reminded his generals that they should also be willing to face danger in combat. Fredendall rarely visited the front lines and often ignored advice from commanders who had actually seen the battlefield. He also spread out his units too much, making it hard for them to support each other during attacks.

During the Battle of Kasserine Pass, Eisenhower sent Ernest N. Harmon to check on the fighting and help the Allied commanders. Harmon noticed that Fredendall and his boss, Anderson, rarely met and did not work well together. Fredendall also had arguments with his 1st Armored Division commander, Orlando Ward, and left him out of important meetings.

Allied forces often lacked air support during key attacks. Commanders also placed units in positions where they could not help each other. Soldiers later remembered being confused by conflicting orders from different generals. Harmon heard many complaints about Fredendall's leadership, with some officers calling it confused and out of touch.

On March 5, 1943, after the American defeat at Kasserine Pass, Eisenhower visited II Corps headquarters. He asked Brigadier General Bradley what he thought of the command. Bradley replied that it was "pretty bad" and that all the division commanders had lost trust in Fredendall. British General Sir Harold Alexander, the 18th Army Group commander, also told Eisenhower he wanted Fredendall replaced. Eisenhower offered the command to Harmon, but Harmon refused, saying it would be wrong to benefit from his own negative report.

Eisenhower then decided that George S. Patton would replace Fredendall. On March 5, 1943, Eisenhower personally flew to Tebessa to tell Fredendall he was being replaced. Eisenhower tried to make it seem like a normal reassignment to protect Fredendall's reputation. On March 6, 1943, Patton officially took over from Fredendall. Patton had not liked Fredendall before the war. After a short meeting, Patton relieved him, saying the II Corps was "primarily a tank show and I know more about tanks." Patton initially wrote that Fredendall was a "great sport" but later, after seeing the state of the command, he changed his mind, writing, "I cannot see what Fredendall did to justify his existence."

Fredendall was the first of seven American corps commanders in World War II to be removed from command. Despite this, he received one more promotion in June 1943, becoming a lieutenant general.

Reassignment and Stateside Duty

At Eisenhower's suggestion, Fredendall returned to the United States. Eisenhower's aide told President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Fredendall should be given a training command. So, Fredendall spent the rest of the war in the U.S., training soldiers. Because he was not officially punished by Eisenhower, he was able to be promoted to lieutenant general and was even welcomed as a hero when he returned home.

While commanding the Central Defense Command and the U.S. Second Army in Memphis, Tennessee, Fredendall oversaw training and military exercises. He initially gave interviews to the press. However, after a sarcastic comment about his leadership in Time magazine, Fredendall stopped giving interviews. It was common for commanders who had struggled in battle to be sent to training commands back home. This did not help their reputation or the morale of the soldiers they were training.

Author Charles B. MacDonald said Fredendall was a "man of bombast and bravado in speech and manner [who] failed to live up to the image he tried to create." Historian Carlo D'Este called Fredendall "...one of the most inept senior officers to hold a high command during World War II." Ernest N. Harmon, the commander of the 2nd Armored Division, said in his report after the Kasserine battles that Fredendall was both morally and physically a coward.

Fredendall served until the end of the war in 1945 and retired on March 31, 1946.

Death

Fredendall died in San Diego, California, on October 4, 1963. He is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery with his wife, Crystal Daphne Chant.

Commands Held

- 1936–1938: Commanding Officer, 57th Infantry Regiment

- October 9, 1940 – August 18, 1941: Commander, 4th Infantry Division

- June 15, 1942 – October 9, 1942: Commander, XI Corps

- October 10, 1942 – March 5, 1943: Commander, II Corps

- November 1942: Commander, Central Task Force, Operation Torch, North Africa

- April 25, 1943 – April 1, 1946: Commander, Second United States Army

- April 25, 1943 – January 15, 1944: Commander, Central Defense Command

Awards and Medals

Fredendall received several awards for his service, including:

- Army Distinguished Service Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Border Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

See also

In Spanish: Lloyd Fredendall para niños

In Spanish: Lloyd Fredendall para niños

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |