Lesley J. McNair facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lesley J. McNair

|

|

|---|---|

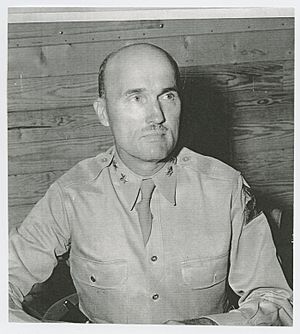

McNair as Army Ground Forces commander, circa 1942

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Whitey |

| Born | May 25, 1883 Verndale, Minnesota, United States |

| Died | July 25, 1944 (aged 61) Saint-Lô, Normandy, France |

| Buried |

Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, France

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1904–1944 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 0-1891 |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | Battery C, 4th Field Artillery Regiment Battery D, 4th Field Artillery Regiment Reserve Officers' Training Corps, Purdue University 2nd Battalion, 16th Field Artillery Regiment 2nd Battalion, 83rd Field Artillery Regiment Civilian Conservation Corps District E, Seventh Corps Area 2nd Field Artillery Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division< United States Army Command and General Staff School Army Ground Forces First United States Army Group (fictitious) |

| Battles/wars | Vera Cruz Expedition Pancho Villa Expedition< World War I World War II

|

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) | Clare Huster (m. 1905-1944, his death) |

| Children | 1 |

Lesley James McNair (May 25, 1883 – July 25, 1944) was a high-ranking United States Army officer. He served in both World War I and World War II. During his life, he reached the rank of lieutenant general. He was killed in action during World War II and was later promoted to general after his death.

McNair was born in Minnesota and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1904. He was an officer in the Field Artillery. He also had experience with weapons design and testing. He served in the Veracruz occupation and the Pancho Villa Expedition. In World War I, he helped train soldiers for the 1st Division. He also worked on artillery training for the American Expeditionary Forces. His excellent work led to him becoming a temporary brigadier general at age 35. This made him the Army's youngest general at the time.

With over 30 years of experience in weapons, training, and leadership, McNair was chosen to lead Army Ground Forces in World War II. In this role, he was very important in planning, equipping, and training Army units in the U.S. before they went to fight overseas. He focused on advanced officer education, new weapons, better strategies, and realistic combat training. This helped the Army become modern and successful in World War II. He was killed by friendly fire in France during Operation Cobra. This happened when U.S. bombs accidentally hit his position near Saint-Lô.

Contents

General Lesley J. McNair: Early Life & Military Start

Growing Up in Minnesota

Lesley McNair was born in Verndale, Minnesota, on May 25, 1883. He was the second of six children. His parents, James and Clara McNair, moved to Minneapolis so he and his siblings could finish high school. After graduating from South High School in 1897, he tried to get into the United States Naval Academy.

While waiting for the Naval Academy, he studied mechanical engineering and statistics at the Minnesota School of Business. In 1900, he decided to try for the United States Military Academy (West Point) instead. He passed the exam and started there in August 1900. His classmates called him "Whitey" because of his light blond hair.

West Point & First Assignments

McNair graduated from West Point in 1904. He was ranked 11th in his class of 124 students. This high ranking allowed him to choose the artillery branch. His first job was as a platoon leader at Fort Douglas, Utah.

He soon asked to work for the Ordnance Department. This department deals with weapons and ammunition. He passed the test and was sent to Sandy Hook Proving Ground in New Jersey. Here, he became very interested in testing new military equipment. He worked on improving mountain guns used by soldiers in tough, hilly areas.

From 1905 to 1906, McNair worked for the Army's Chief of Ordnance. Then he went to the Watertown Arsenal. There, he studied metals and other scientific topics on his own. He learned how to test materials like bronze and steel to make better cannons. His background in business and statistics helped him succeed in testing. Because of this, the Army often asked him to lead groups that tested weapons and equipment. He was promoted to temporary first lieutenant in 1905 and permanent first lieutenant in 1907. In May 1907, he became a temporary captain.

McNair's Pre-World War I Service

Artillery Command & Innovation

In 1909, McNair returned to the Artillery branch. He was assigned to the 4th Field Artillery Regiment in Wyoming. He commanded Battery C and was praised for his leadership. Another officer, Jacob L. Devers, who later became a general, said McNair was an excellent commander.

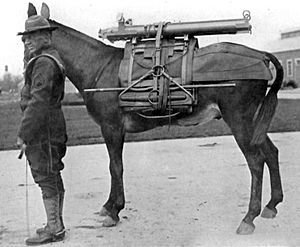

McNair also worked on making pack howitzers and other equipment better. These were used by mules to carry artillery in mountains. In 1909, he commanded Battery D during tests of different types of defenses. In 1911, he received three patents for his new artillery projectiles.

His skills in engineering and testing became well-known. In 1912, the head of the United States Army Field Artillery School specifically asked for him. McNair helped organize data from 7,000 artillery rounds fired in tests. This helped create firing tables for artillery crews. In 1913, he spent seven months in France studying their army's artillery training.

Veracruz & Pancho Villa Expeditions

In April 1914, McNair became a permanent captain. From April to November 1914, he served in the Veracruz Expedition in Mexico. He was the supply officer for his regiment. This meant he was in charge of getting, storing, and giving out all the regiment's equipment and weapons.

In 1915 and 1916, he returned to the Field Artillery School. He continued to work on artillery procedures and experimented with different types of artillery. This was important as the Army prepared for possible involvement in World War I. He then joined the Pancho Villa Expedition on the Texas-Mexico border, where he commanded an artillery battery.

McNair's Role in World War I

Training the American Expeditionary Forces

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, McNair was promoted to major. He became an instructor at an officer training camp in Texas. After that, he joined the new 1st Division. He was responsible for training soldiers and units before they went to France.

On the ship to France, McNair shared a room with George C. Marshall, who would later become a very important general. They became good friends and colleagues.

In August 1917, McNair was promoted to temporary lieutenant colonel. He worked at the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) headquarters in France. He was in charge of artillery training and tactics. He became a temporary colonel in June 1918 and a temporary brigadier general in October. At 35, he was the youngest general in the Army.

His superiors were very impressed with his skills. After the war, he received the Army Distinguished Service Medal from General John J. Pershing. He also received the French Legion of Honor.

In June 1919, after the war ended, McNair joined a board that studied how to provide artillery support to infantry. This board, called the Lassiter Board, reviewed wartime activities and made recommendations for the Army's future.

Building the Army: McNair's Post-WWI Impact

Teaching and Doctrine Development

McNair soon left the Lassiter Board to become a faculty member at the Army's School of the Line. This school trained officers on how to plan and manage large military operations. McNair returned to his permanent rank of major. He stayed at the school until 1921.

He helped design the school's courses. He also played a key role in writing the Field Service Regulations, which was the Army's main guide for training. He was one of the main authors of the 1923 revision of these regulations.

Coastal Defense and War Planning

In 1921, McNair was sent to Fort Shafter in Hawaii. He became the assistant chief of staff for operations for the Army's Hawaiian Department. In Hawaii, he got involved in a debate about how to best defend the coast. This involved the Coast Artillery and the Army Air Service.

McNair was known for being fair in his analysis. He formed a committee to study the strengths of both branches. They looked at how to defend Army and Navy bases on Oahu from attack. The committee tested both coastal artillery and bomber aircraft. They concluded that coastal artillery was good for defense if there was enough equipment to detect enemy ships and planes. Bombers were less accurate but better at destroying ships farther from shore.

McNair also helped update War Plan Orange. This was a joint Army and Navy plan to defend against a possible attack on Hawaii by Japan. He added plans for using chemical weapons, declaring martial law, and how to defend while waiting for help from the U.S. mainland.

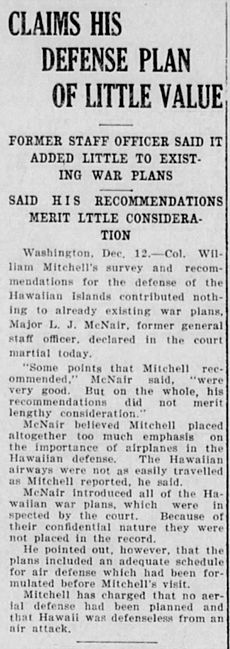

In 1924 and 1925, McNair's work was criticized by Major General Mason Patrick, head of the Air Service. Patrick said McNair's findings underestimated bombers. However, McNair's work was defended by others who said his tests were fair. McNair also testified in the 1925 court-martial of Brigadier General Billy Mitchell. Mitchell was accused of insubordination for strongly pushing for a separate Air Force. McNair's testimony helped show that Mitchell's claims about Hawaii's defense were wrong. Despite the controversy, McNair's reputation for clear thinking and leadership grew.

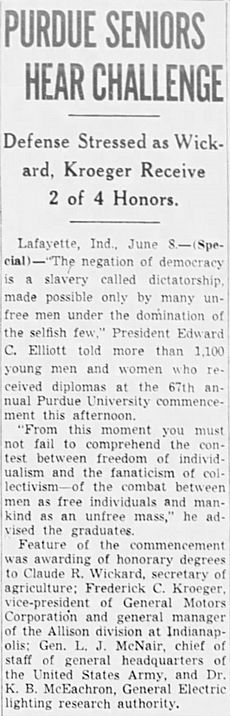

Training Future Officers

In 1924, McNair became the head of the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) program at Purdue University. ROTC trained college students to become military officers. Purdue's program was a motorized field artillery unit, which fit McNair's skills perfectly.

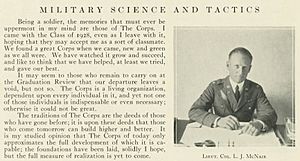

Purdue's president, Edward C. Elliott, strongly supported ROTC. McNair also became a strong supporter of military readiness. He wrote many articles and letters arguing for military training and against the idea of pacifism (avoiding all war). He also wrote about changing the Army's officer promotion system to focus on skill rather than just how long someone had served.

McNair made many improvements to Purdue's ROTC program. His leadership helped increase student participation and improve morale. The program became the Army's largest light artillery unit. He stayed at Purdue until 1928.

Advanced Military Education

In 1928, McNair was promoted to lieutenant colonel and attended the United States Army War College. This was the highest-level education for Army officers. The program focused on how to manage large wartime efforts, including economics, industry, and supplies. It also covered how to organize, train, and use large military units in combat.

McNair's final project at the War College was about how the War Department could best use money for unit training. His commandant called it "a study of exceptional merit." McNair received a "superior" evaluation and was recommended for high command.

Improving Artillery Tactics

After War College, McNair became the assistant commandant of the Field Artillery Center and School. He worked to solve problems with artillery tactics that had existed since World War I. These included slow movement, poor communication, and overly complex firing methods.

McNair supported new ideas to make artillery faster and more accurate. This included letting officers closer to the front lines direct artillery fire. They also developed ways to improve accuracy, like using forward observers who could see where shells landed. McNair supported these changes and protected those who were trying to make them happen.

He also agreed that artillery should be controlled from a higher level, like a battalion, rather than individual batteries. This allowed commanders to quickly send artillery support where it was most needed. McNair had supported this idea since World War I. These changes became standard for how field artillery units operated in World War II.

When McNair finished his assignment in 1933, he received top marks. He was recommended for promotion to colonel and for leading a regiment or brigade.

Leading Units and Civilian Programs

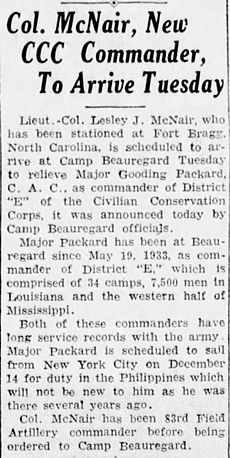

McNair commanded the 2nd Battalion, 16th Field Artillery Regiment at Fort Bragg from July to October 1933. The unit was then renamed the 2nd Battalion, 83rd Field Artillery Regiment. He commanded this unit until August 1934.

In August 1934, McNair was put in charge of District E of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This program helped thousands of young men during the Great Depression. District E had 33 camps in Louisiana and Mississippi. McNair gained experience in organizing, housing, feeding, and supervising thousands of young men. This experience was very useful later when he became a high-ranking Army commander. He was promoted to colonel in May 1935.

Innovations in Artillery and Command

As executive officer for the Army's Chief of Field Artillery, McNair continued to test new equipment. He worked with Hotchkiss Anti-Tank Guns and Anti-Aircraft Guns. He also studied using autogyros (early helicopters) to spot targets for artillery. This was a very forward-thinking idea. In January 1937, McNair was promoted to brigadier general.

In March 1937, McNair commanded the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade. The Army was testing new ways to organize divisions, moving from "square" divisions (used in WWI) to "triangular" divisions. The 2nd Infantry Division was chosen for these tests, and McNair helped lead the effort. The triangular division model was adopted and became the standard for infantry divisions in World War II. His commander rated him as superior and recommended him for even higher command.

Modernizing Officer Training

In March 1939, McNair was chosen to lead the United States Army Command and General Staff College. The Army Chief of Staff, General Malin Craig, wanted to update the college's teaching methods. He believed McNair was the right person for the job. George Marshall, who was Craig's deputy, also felt the curriculum needed to be more flexible. They wanted to prepare officers for the fast-moving offensive battles expected in World War II.

McNair shortened the course length to help National Guard and Reserve officers attend. He also updated the Army's main doctrine document, the Field Service Manual. This work helped shape how the Army would operate in World War II. McNair continued to receive top ratings for his performance.

McNair's Leadership in World War II

Shaping Army Ground Forces

In July 1940, McNair became chief of staff for General Headquarters, United States Army (GHQ). This organization was created to prepare the Army for World War II. George Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, largely let McNair run GHQ. McNair focused on organizing, equipping, and training soldiers.

McNair played a big part in planning and running the 1940 and 1941 Louisiana Maneuvers and Carolina Maneuvers. These were large war games that helped the Army learn about training, leadership, and tactics. They also helped identify the best senior officers for top positions. McNair was promoted to temporary major general in September 1940 and temporary lieutenant general in June 1941.

In March 1942, the Army created three new main commands. McNair was put in charge of Army Ground Forces (AGF). His job was to grow the Army's ground forces from 780,000 soldiers in 1942 to over 8 million by 1945. He was in charge of all Army schools, training centers, and mobilization camps. He also oversaw the four main combat branches: Infantry, Field Artillery, Cavalry, and Coast Artillery. He also had authority over new "quasi-arms" like Airborne, Armor, Tank Destroyer, and Antiaircraft Artillery.

Training Soldiers for Combat

McNair organized and supervised basic soldier training. This helped individuals learn core skills before moving to more complex unit training. He insisted on realistic training, using live ammunition or simulators. This prepared soldiers and commanders for real combat overseas.

He faced challenges with training National Guard units because they had less prior military experience. He also believed that most National Guard senior commanders should not lead beyond the rank of colonel. He thought full-time professional officers should lead divisions and higher units. He was mostly successful in this, with most National Guard division commanders being replaced by regular Army officers.

The Army initially planned to create up to 350 divisions. This number was later reduced to 90 divisions. This was partly because U.S. divisions were better equipped and motorized than those of their enemies. Other factors included the Soviet Union joining the Allies and the need for enough workers in the U.S. for food and weapons production.

To achieve the goal of 90 divisions, McNair and his staff created new plans. These plans reduced the number of soldiers needed for each division. By 1945, the Army could field 89 divisions with the same number of soldiers that would have only manned 73 divisions in 1943.

McNair also helped create airborne units. By 1943, he was convinced that the Army needed division-sized airborne organizations. This led to the creation of the Airborne Command. It also led to the 82nd and 101st Infantry Divisions becoming airborne units.

The Army also created "light divisions" for special terrain. Three existing divisions were reorganized for mountains and jungles. However, two of them were too small for combat and were changed back to regular infantry divisions. The 10th Mountain Division did serve in combat in the Italian mountains. Overall, McNair's work on organizing divisions was successful. It provided enough units to win the war while keeping enough civilians for production.

Managing Soldier Replacements

As AGF commander, McNair worked on how to replace soldiers who were killed or wounded in units. Instead of sending whole new units, the Army decided to send individual replacement soldiers. This was partly to save space on transport ships for equipment.

This system caused problems. New soldiers often had trouble fitting in with veterans. They also joined units already fighting, so there was little time for training. McNair tried to improve the system. He created a Classification and Replacement Division. He also streamlined the physical and mental tests for soldiers. The AGF also set up two new replacement centers at Fort Meade, Maryland, and Fort Ord, California.

Because infantry soldiers had the most casualties, McNair argued for sending the best recruits to the AGF. He also tried to boost morale for infantry soldiers. He helped create the Expert Infantryman Badge. He also started the "Soldier for a Day Initiative" for civilian leaders.

However, by late 1944, the replacement system struggled. Soldiers from support roles were sent to the front lines. Training was cut short. Units became worn down, and morale dropped.

Public Relations and Recruitment

McNair tried to improve public relations to attract high-quality recruits to the AGF. He created a Special Information Section (SIS) within his staff. This group worked with writers, artists, and filmmakers to highlight the importance of infantry soldiers. McNair even wrote to magazine and newspaper publishers for their help.

On Armistice Day in November 1942, McNair gave a radio speech called "The Struggle is for Survival." He described the fighting skills of Japanese and German soldiers. He said that only similar qualities in American ground troops would lead to victory. The public generally liked his speech. However, it did not significantly improve recruitment for the Army Ground Forces. Volunteers still preferred the Air Forces and Supply Services.

African-American Soldiers

During World War II, the Army had rules for African Americans. They had to be allowed into the Army in numbers that matched their share of the population. The Army also had to create separate African American units in each branch. Qualified African Americans could also become officers.

The AGF activated and trained African American units in all ground forces branches. Black soldiers who finished officer training were assigned to these units. By June 1943, nearly 170,000 African Americans were training at AGF facilities. This was about 10.5 percent of its personnel, matching their percentage in the U.S. population.

The AGF organized and trained many African American units. These included the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions. They also created the 2nd Cavalry Division. By 1943, the AGF had created almost 300 African American units. These included the 452nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion and the 761st Tank Battalion.

McNair suggested having separate battalions for African American soldiers. He believed they could be used effectively for tasks like guarding supply lines. This proposal was adopted, and the initial training period was extended. African American officers usually filled lower-ranking positions. White officers held higher-ranking and command positions.

Debate Over Anti-Tank Weapons and Tanks

Developing and using anti-tank weapons was a challenge. McNair preferred towed weapons, like the M3 gun. He believed they were an efficient way to defeat enemy tanks. This would free up U.S. tanks for offensive operations.

When the M3 gun proved less effective, the Army developed tank destroyers. These were self-propelled vehicles with thinner armor but faster movement. The Army created a separate Tank Destroyer Center. However, this meant that commanders of armor and infantry units often had little experience with anti-tank weapons.

The Army eventually fielded self-propelled anti-tank weapons like the M3 Gun Motor Carriage and the M10 tank destroyer. However, the ongoing debate about which weapons to use and how to use them caused problems. Commanders in combat had to find their own ways to use anti-tank guns effectively. The AGF then used these lessons to improve training for new soldiers.

At the start of World War II, the U.S. used the M3 Lee and M4 Sherman tanks. After battles in North Africa, some commanders felt the U.S. needed heavier tanks to fight German Tiger I and Panther tanks. McNair disagreed. He believed that smaller, heavily armed tank destroyers were better. He also worried that heavier tanks would take up too much space on cargo ships.

In December 1943, other commanders convinced George Marshall that a heavier tank was needed. This led to the M26 Pershing tank. McNair still opposed it, saying the M4 was good enough. He believed tank-on-tank battles were unlikely. The Pershing tanks were sent to Europe but arrived too late to greatly affect the war.

McNair also played a key role in making armored divisions smaller in 1942 and 1943. He believed armored divisions were too large. He thought tanks should mainly support infantry and make fast advances. The downsizing allowed the creation of separate tank battalions. These could be sent to support infantry divisions as needed.

Death and Legacy

Killed in Action

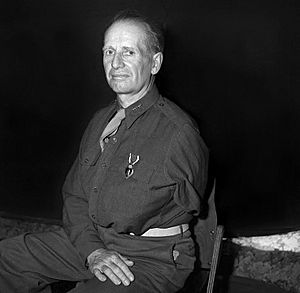

In 1943, McNair visited North Africa to see how AGF troops were doing. He wanted to improve training. On April 23, he was observing fighting in Tunisia when he was wounded by bomb fragments. A soldier nearby was killed.

McNair went to the European Theater in 1944. He was considered for command of the Fifteenth United States Army. He was also chosen to command the fake First United States Army Group (FUSAG). This was part of Operation Quicksilver, a plan to trick the Germans about the real landing sites for the Invasion of Normandy.

In July 1944, McNair was in France to observe troops during Operation Cobra. He was also there to make the Germans believe he was leading FUSAG. He was killed near Saint-Lô on July 25. This happened when bombs from the Eighth Air Force accidentally hit his position. Over 100 U.S. soldiers were killed, and nearly 500 were wounded. This was one of the first times the Allies used heavy bombers to support ground troops.

McNair was buried at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in France. His funeral was kept secret to maintain the FUSAG deception. Only a few top generals attended. When his death was reported, it first said he was killed by enemy fire. The truth about the friendly fire was reported later in August. McNair is the highest-ranking military officer buried at the Normandy cemetery. He was one of four American lieutenant generals who died in World War II. In 1954, he was promoted to general after his death. His gravestone was updated in 2010 to show his higher rank.

Hearing Loss and Its Impact

McNair started losing his hearing early in his career. The problem got worse over time. By the time he became a senior commander, his hearing loss was severe. He learned to read lips and avoided large meetings where hearing was difficult. He worried his hearing might force him to retire. However, General Marshall allowed him to continue serving. His hearing loss might have prevented him from leading troops in combat during World War II. But Marshall valued his skills as an organizer and trainer too much to let him go.

McNair's Enduring Legacy

McNair was highly respected by his peers. His performance reviews always gave him the highest ratings. General Marshall also held him in high regard. This was shown by McNair's important role in World War II and being considered for top commands. Mark W. Clark, another general, called McNair "one of the most brilliant, selfless and devoted soldiers" he had ever met.

McNair's main legacy is his role as "the brains of the Army." He was key in designing units (like the triangular division), improving officer education, updating military strategies, and developing weapons. He also trained soldiers and units, especially between World War I and II. He was one of the main architects of the U.S. Army that fought in World War II.

Another lasting legacy is his training method. He believed in starting with basic soldier skills and then building up to large unit exercises. These exercises closely simulated real combat. These ideas are still core principles for Army training today.

Historians still debate some of McNair's decisions. These include the individual replacement system and the issues with tanks versus anti-tank guns. Some historians say the replacement system was inefficient. Others argue it was necessary for keeping units in combat. Regarding tanks, some say McNair understood the limits of available weapons and developed the best strategies. Others argue his views on heavy tanks were outdated and hurt the Army's performance.

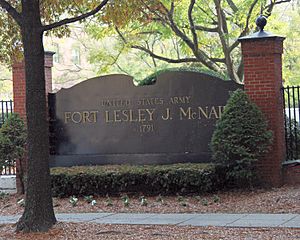

Awards and Honors

McNair received honorary degrees from Purdue University in 1941 and the University of Maine in 1943. A temporary bridge over the Rhine River in Germany was named the Lesley J. McNair Bridge in 1945. Washington Barracks in Washington, D.C., was renamed Fort Lesley J. McNair in 1948. Many roads and buildings on U.S. Army posts are named "McNair." These include McNair Hall at Fort Sill and Fort Leavenworth. McNair Barracks in Berlin, Germany, was also named for him.

McNair was inducted into the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame in 1969. This honors soldiers who made important contributions to the Army. In 2005, he was also inducted into the U.S. Army's Force Development Hall of Fame.

Family Life

Lesley McNair married Clare Huster (1882–1973) on June 15, 1905. They had one son, Douglas (1907–1944).

Clare McNair's Work

After McNair's death, Clare McNair worked for the United States Department of State. She investigated working conditions for women in the Foreign Service during World War II. She traveled to many countries to interview employees and suggest improvements.

Douglas C. McNair's Service

Douglas Crevier McNair was born on April 17, 1907. He graduated from West Point in 1928 and became an artillery officer. He rose to the rank of colonel and was chief of staff of the 77th Infantry Division. Douglas was killed in action on the island of Guam on August 6, 1944. This was just 12 days after his father's death. He died during a fight with Japanese soldiers while scouting for a new command post.

Douglas McNair received several awards after his death, including the Silver Star and Purple Heart. He was buried in Hawaii. A temporary camp on Guam and a housing development at Fort Hood, Texas, were named "Camp McNair" and "McNair Village" in his honor.

Military Awards

Lesley McNair received many awards and decorations:

| Army Distinguished Service Medal (with two oak leaf clusters) | |

| Purple Heart (with one oak leaf cluster) | |

| Mexican Border Service Medal | |

| World War I Victory Medal | |

| American Defense Service Medal | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with Arrowhead Device and 2 bronze service stars | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Officer of the Legion of Honor (France) |

Note: Two Distinguished Service Medals, one Purple Heart, and the World War II Victory Medal were awarded after his death.

Dates of Rank

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet | United States Military Academy | August 1, 1900 |

| No insignia in 1904 | Second Lieutenant | Regular Army | June 15, 1904 |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army (Temporary) | July 1, 1905 | |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army | January 25, 1907 | |

| Captain | Regular Army (Temporary) | May 20, 1907 | |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army | July 1, 1909 | |

| Captain | Regular Army | April 9, 1914 | |

| Major | Regular Army | May 15, 1917 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | National Army (Temporary) | August 5, 1917 | |

| Colonel | National Army (Temporary) | June 26, 1918 | |

| Brigadier General | National Army (Temporary) | October 1, 1918 | |

| Major | Regular Army | July 16, 1919 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Regular Army | January 9, 1928 | |

| Colonel | Regular Army | May 1, 1935 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | January 1, 1937 | |

| Major General | Army of the United States (Temporary) | September 25, 1940 | |

| Major General | Regular Army (Permanent) | December 1, 1940 | |

| Lieutenant General | Army of the United States (Temporary) | June 9, 1941 | |

| General | Regular Army (Posthumous) | July 19, 1954 |

Images for kids

-

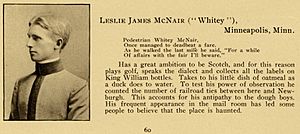

McNair in 1904's Howitzer, the West Point yearbook. The reference to King William bottles describes a brand of Scotch whisky.

-

McNair confers with an umpire during the Louisiana Maneuvers

-

McNair listens as Omar Bradley, 82nd Infantry Division commander, explains a scenario to McNair at the Louisiana Maneuvers

-

Senior officers during the Louisiana maneuvers. Left to right: Mark W. Clark, Chief of Staff, Army Ground Forces; Harry J. Malony, Chief of Staff, Second Army; Dwight D. Eisenhower, Chief of Staff, Third Army; Ben Lear, Commander Second Army; Walter Krueger, Commander Third Army; Lesley J. McNair, Commander Army Ground Forces.

-

McNair and George S. Patton, commander of I Armored Corps review map during training exercise at Desert Training Center, 1942

-

McNair after being awarded the Purple Heart in Tunisia in April 1943, with left arm in sling.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |