Luis de Onís facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luis de Onís y González-Vara

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Minister of Spain to the United States | |

| In office 7 October 1809 – 10 May 1819 |

|

| Preceded by | Valentin de Foronda |

| Succeeded by | Francisco Dionisio Vives |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 June 1762 Cantalapiedra, Salamanca, Spain |

| Died | 17 May 1827 (aged 64) Madrid, Spain |

| Spouse | Federika Christina von Mercklein |

| Profession | Diplomat and ambassador of Spain |

Luis de Onís y González-Vara (born June 4, 1762 – died May 17, 1827) was an important Spanish diplomat. He worked as Spain's special representative to the United States from 1809 to 1819. He is best known for helping to create the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819. This treaty was signed with United States Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and gave Florida to the United States.

Contents

A Look at Luis de Onís's Life

Early Years and Education

Luis de Onís was born in Cantalapiedra, a town in Salamanca, Spain, on June 30, 1762. His father, Joaquin de Onís, was a landowner. Luis learned a lot at home. He started studying Greek and Latin when he was 8 years old. By the time he was 16, he had finished his studies in humanities and law at the University of Salamanca.

Starting a Diplomatic Career

In 1780, when he was 18, Luis de Onís joined his uncle, José de Onís, in Dresden, Germany. His uncle was Spain's ambassador to the Electorate of Saxony. Luis became his uncle's personal secretary and also worked as a trade commissioner. This job allowed him to visit royal courts in cities like Berlin and Vienna.

In 1786, the Spanish government sent Onís on an important mission. They knew that Saxony had the best mining industry in Europe. Spain wanted to bring experienced miners to its colonies in America. Onís went to study at the School of Mines in Freiberg. He learned about mining and found many miners who needed jobs. He convinced a Saxon minister to let him choose 36 miners, including 6 managers, to send to Spain. Because of his success, he was offered a job as a minister to the United States, but he couldn't take it at that time.

In 1792, Onís received an award called the Cross of Charles III of Spain. In 1798, he returned to Spain and worked in Madrid. He was in charge of talks with France. In 1802, he helped with the Treaty of Amiens. Later, he was given special benefits as a "secretary to the King."

After Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain in 1808, the Spanish government moved to Seville. Onís continued his work there. He was offered diplomatic jobs in St. Petersburg and Sweden, but they didn't happen. Finally, the Spanish government, which was fighting Napoleon, decided to send him to the United States.

Ambassador to the United States

On June 29, 1809, Onís was chosen to be Spain's minister to the United States. This meant he had full power to make decisions. He was told to go to New York as soon as possible. His main goals were to keep peace between Spain and the US, get the US to officially recognize King Ferdinand VII as Spain's ruler, and buy supplies for Spain's war against France. He also had to stop French ideas from spreading in the US.

Onís arrived in New York on October 4, 1809. He asked to meet President James Madison, but the US government would not officially recognize him. They said they would stay neutral until the war in Spain was over. So, no one from the US government would talk to him officially. The United States didn't officially recognize Onís as ambassador until December 1815, more than five years after he arrived.

Onís moved to Philadelphia and used a Spanish consular office to work unofficially. He worked hard to stop the United States from moving into Florida. He also watched out for Spanish and Latin American revolutionaries who wanted to use American sympathy for their cause. The US Secretary of State, James Monroe, didn't officially agree with Onís's complaints. However, Monroe secretly supported groups that tried to cause trouble in Spanish areas.

The US took over West Florida in 1810. This happened because the border between Florida and the Louisiana Purchase was unclear. During the War of 1812 between the US and Great Britain, there was a risk of invasion in East Florida. This was a constant worry for Onís. Finally, on December 20, 1815, the US government officially recognized Onís as Spain's Ambassador. He continued to strongly argue for Spain's side.

Meanwhile, the US sent an ambassador to Madrid, John Erving. He had to wait a long time for Spain to officially recognize Onís in the US. Spain's Secretary of State, Pedro Cevallos, didn't want to give up much land in a treaty. He tried to delay talks. Onís also tried to delay official recognition of the US embassy by Spain.

During his time in the United States, Onís wrote several articles criticizing the US government. He used the pen name "Verus," which means "True" in Latin. He warned Spanish leaders in Mexico and Cuba about the US's plans to expand. During the Mexican War of Independence, he had a network of spies. They tried to stop rebels from getting help from the US. They also fought against "insurgent corsairs," who were like pirates working for the new Spanish American republics.

The Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty was signed on February 22, 1819. It took two years of difficult talks to reach this agreement. The French ambassador, Hyde de Neuville, helped by supporting Spain's side. He argued against strong opinions from people like Henry Clay in the US Congress and General Andrew Jackson, who disliked Spain's presence in East Florida.

Spain delayed officially approving the treaty for two years. They wanted to use it to stop the United States from supporting revolutionaries in South America. Once the treaty was signed, the US Senate quickly approved it. But because of Spain's delay, the US Senate had to approve it again. This time, some people, like Henry Clay, wanted Spain to also give up Texas. However, the Senate voted against this idea. The Senate approved the treaty a second time on February 19, 1821. Spain had approved it on October 24, 1820. The treaty officially began on February 22, 1821, two years after it was first signed.

The treaty had 16 parts. Half of them solved problems that had been argued about since 1783. Spain gave all its lands east of the Mississippi River, known as the Floridas, to the United States. The hardest part was deciding the borders to the west and northwest of the Mississippi. Onís tried very hard to keep Texas, New Mexico, and California for Spain.

People in the US and the Senate were very happy about the treaty. Onís returned to Europe. He believed that if he hadn't signed the treaty, Spain would have lost all its territories as far west as the Rio Grande.

The Adams–Onís Treaty was a big step in US expansion. It gave East Florida to the US. It also ended arguments over West Florida, which the US had already taken some parts of. The treaty clearly set the border with Spanish Mexico, making Spanish Texas part of Mexico. This made the borders of the Louisiana Purchase much clearer. Spain also gave up its claims to the Oregon Country to the US. For Spain, it meant they kept Texas and had a safe area between their lands in California and New Mexico and the US territories.

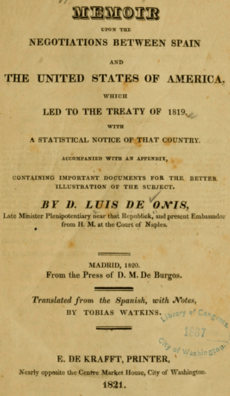

In 1820, Onís published a book about the treaty talks. It was translated into English by Tobias Watkins and published in the US in 1821.

Honors and Final Years

In 1818, the Spanish Cortes (like Spain's parliament) gave Onís the title of Regidor perpetuo de Salamanca. This meant he was a "Perpetual alderman of Salamanca," a title that could be passed down to his male children. In 1819, Onís received the "American Grand Cross" award. He was also made a "Councilor of State" and was chosen to be a minister in St. Petersburg. However, a revolution in 1820 stopped him from taking that job. The new government sent him to the embassy in Naples instead.

In the same year, he published a two-volume book called Memoria sobre las Negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América. This book was about his role in the talks that led to the 1819 treaty. His last diplomatic mission was to London in February 1821. There, he worked to prevent European countries from recognizing the new countries in Hispanic America, following the US example. In November 1822, Onís returned to Madrid. He died there on May 17, 1827, after a short illness.

Personal Life

Luis de Onís married Federika Christina von Mercklein in Dresden on August 9, 1788. They had three children: Mauricio, Narciss, and Clementina.

See also

In Spanish: Luis de Onís para niños

In Spanish: Luis de Onís para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |