Matsuo Bashō facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Matsuo Bashō

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Bashō by Hokusai, late 18th century

|

|||||

| Native name |

松尾 芭蕉

|

||||

| Born | Matsuo Kinsaku (松尾 金作) 1644 Near Ueno, Iga Province |

||||

| Died | November 28, 1694 (aged 49–50) Osaka |

||||

| Pen name | Sōbō (宗房) Tōsē (桃青) Bashō (芭蕉) |

||||

| Occupation | Poet | ||||

| Nationality | Japanese | ||||

| Notable works | Oku no Hosomichi | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 松尾 芭蕉 | ||||

| Hiragana | まつお ばしょう | ||||

|

|||||

Matsuo Bashō, (松尾 芭蕉, 1644 – November 28, 1694) was a very famous poet from Japan's Edo period. He was born Matsuo Kinsaku, (松尾 金作) and later used the name Matsuo Chūemon Munefusa, (松尾 忠右衛門 宗房).

During his life, Bashō was known for his collaborative poems called haikai no renga. Today, he is seen as the greatest master of haiku. Back then, these short poems were called hokku. He also wrote interesting travel stories. One famous one is Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton (1684). This was written after his trip to Kyoto and Nara.

Many of Bashō's poems are still famous today. You can find them on monuments and traditional sites in Japan. Even though he is known for his hokku in other countries, Bashō himself thought his best work was in leading and joining renku poems. He once said, "Many of my followers can write hokku as well as I can. Where I show who I really am is in linking haikai verses."

Bashō started writing poetry when he was young. He quickly became well known across Japan. He earned a living as a teacher. But then he decided to leave city life and travel. He wandered across the country to find ideas for his writing. His poems were inspired by what he saw and felt around him. He often captured a scene's feeling in just a few simple words.

Contents

Biography of Matsuo Bashō

Early Life and Poetry Beginnings

Matsuo Bashō was born in 1644. His home was near Ueno, in Iga Province. His family had a samurai background. His father was likely a landowning farmer with some special rights.

We do not know much about his childhood. In his late teenage years, Bashō worked for Tōdō Yoshitada. He probably had a simple job, perhaps as a page.

Bashō and Yoshitada both loved haikai no renga. This was a type of poem written by several people together. The first verse was called a hokku. It had a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. Later, this hokku became known as a haiku when it stood alone. Bashō used the pen name Sōbō for his poetry. His first known poem was published in 1662.

In 1665, Bashō and Yoshitada wrote a long poem together. It had one hundred verses. In 1666, Yoshitada suddenly died. This ended Bashō's life as a servant. It is believed that Bashō then left home. He gave up any chance of becoming a samurai.

Bashō was not sure if he should become a full-time poet. He said that "the alternatives battled in my mind and made my life restless." Poetry was not seen as a serious art form back then. But his poems kept being published. In 1672, he moved to Edo (modern Tokyo). He wanted to study poetry more deeply there.

Becoming a Famous Poet

In Nihonbashi, Bashō's poetry quickly became popular. People liked his simple and natural style. By 1674, he joined the main group of haikai poets. He learned special teachings from Kitamura Kigin. He wrote a hokku about the Shogun:

甲比丹もつくばはせけり君が春 kapitan mo / tsukubawasekeri / kimi ga haru

the Dutchmen, too, / kneel before His Lordship— / spring under His reign. [1678]

In 1675, Nishiyama Sōin, a famous haikai leader, came to Edo. Bashō was one of the poets asked to write with him. At this time, Bashō chose a new pen name: Tōsei. By 1680, he had twenty students. They published a book of their poems. This showed how talented Tōsei was. That winter, Bashō moved to Fukagawa. He wanted a quieter life away from the public eye. His students built him a simple hut. They planted a Japanese banana tree (芭蕉, bashō) in the yard. This tree gave Bashō his new pen name and his first real home. He loved the plant. But he did not like the wild grass growing next to it:

ばしょう植ゑてまづ憎む荻の二葉哉 bashō uete / mazu nikumu ogi no / futaba kana

by my new banana plant / the first sign of something I loathe— / a miscanthus bud! [1680]

Even with his success, Bashō felt unhappy and alone. He started practicing Zen meditation. But it did not seem to calm him. In 1682, his hut burned down. Soon after, in 1683, his mother died. He then stayed with a friend. In the winter of 1683, his students gave him a second hut in Edo. But he still felt sad. In 1684, his student Takarai Kikaku published a collection of poems. It was called 'Shriveled Chestnuts (虚栗, Minashiguri). Later that year, Bashō left Edo. This was the first of his four big journeys.

Bashō traveled alone. He went on less-traveled roads. These roads were thought to be very dangerous. At first, Bashō worried he might die or be attacked. But as his trip went on, he felt better. He enjoyed being on the road. Bashō met many friends. He liked seeing the changing scenery and seasons. His poems became less about his inner thoughts. They were more about what he saw around him:

馬をさへながむる雪の朝哉 uma wo sae / nagamuru yuki no / ashita kana

even a horse / arrests my eyes—on this / snowy morrow [1684]

His trip took him from Edo to Mount Fuji, Ueno, and Kyoto. He met poets who wanted his advice. He told them not to follow the popular Edo style. He even said his own book, Shriveled Chestnuts, had "many verses that are not worth discussing." Bashō returned to Edo in the summer of 1685. He wrote more hokku and thought about his life:

年暮ぬ笠きて草鞋はきながら toshi kurenu / kasa kite waraji / hakinagara

another year is gone / a traveler's shade on my head, / straw sandals at my feet [1685]

When Bashō came back to Edo, he happily taught poetry again. He worked at his bashō hut. But secretly, he was already planning another trip. The poems from his journey were published as Nozarashi Kikō. In early 1686, he wrote one of his most famous haiku:

古池や蛙飛びこむ水の音 furu ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto

an ancient pond / a frog jumps in / the splash of water [1686]

This poem became famous right away. In April, poets in Edo held a haikai no renga contest about frogs. It seemed to be a tribute to Bashō's hokku. Bashō stayed in Edo. He kept teaching and holding contests. He took a short trip in autumn 1687 to watch the moon. In 1688, he took a longer trip to Ueno for the Lunar New Year. At home, Bashō sometimes kept to himself. He would refuse visitors, but then enjoy their company. He also had a quiet sense of humor, as seen in this hokku:

いざさらば雪見にころぶ所迄 iza saraba / yukimi ni korobu / tokoromade

now then, let's go out / to enjoy the snow ... until / I slip and fall! [1688]

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

Bashō planned another long journey. This trip would become his most famous work, Oku no Hosomichi, or The Narrow Road to the Deep North. On May 16, 1689, he left Edo. His student, Kawai Sora (河合 曾良), went with him. They traveled north to Hiraizumi. Then they walked to the western side of the island. They visited Kisakata and slowly walked back along the coast. During this 150-day journey, Bashō traveled about 2,400 kilometers. He went through the northeastern parts of Honshū. He returned to Edo in late 1691.

By the time Bashō reached Ōgaki, he had finished writing about his journey. He spent three years editing it. The final version was completed in 1694. It was published after he died, in 1702. The book was a huge success. Many other traveling poets followed his path. This work is often seen as his greatest achievement. It includes hokku like:

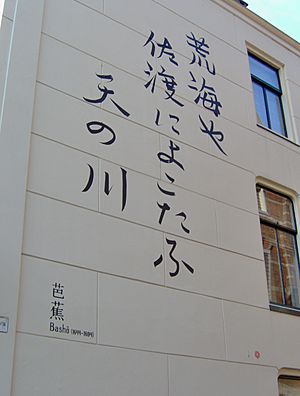

荒海や佐渡によこたふ天河 araumi ya / Sado ni yokotau / amanogawa

the rough sea / stretching out towards Sado / the Milky Way [1689]

Bashō's Final Years

When Bashō returned to Edo in the winter of 1691, he lived in his third bashō hut. His students had provided it again. This time, he was not alone. He took in his nephew Toin and a female friend, Jutei. Both were recovering from illness. Many important visitors came to see him.

Bashō continued to feel restless. He wrote to a friend that "disturbed by others, I have no peace of mind." He earned money by teaching and attending haikai parties. In August 1693, he closed the gate to his hut. He refused to see anyone for a month. Finally, he changed his mind. He adopted the idea of karumi, or "lightness." This was a Buddhist idea about accepting the everyday world.

Bashō left Edo for the last time in the summer of 1694. He spent time in Ueno and Kyoto before arriving in Osaka. He became sick with a stomach illness. He died peacefully, surrounded by his students. He did not write a formal death poem. But his last recorded poem, written during his illness, is seen as his farewell:

旅に病んで夢は枯野をかけ廻る tabi ni yande / yume wa kareno wo / kake meguru

falling sick on a journey / my dream goes wandering / over a field of dried grass [1694]

Bashō's Influence and Legacy

Early Views of His Poetry

Bashō wanted his hokku to show real feelings and surroundings. He did not just stick to old rules. Even when he was alive, people admired his poetry style. After he died, his fame grew even more. Some of his students wrote down what he said about his own poems.

In the 1700s, people loved Bashō's poems even more. Commentators tried hard to find hidden meanings in his hokku. They looked for links to history, old books, and other poems. They often praised his clever references. In 1793, Bashō was honored as a god by the Shinto religion. For a time, it was considered wrong to criticize his poetry.

In the late 1800s, this period of complete praise for Bashō ended. Masaoka Shiki, a famous critic, openly disagreed with Bashō's style. However, Shiki also helped make Bashō's poetry known in English. He also helped Japanese people understand it better. Shiki created the term haiku. This replaced hokku for the 5–7–5 poem form that stood alone. He thought this was the most artistic part of haikai no renga.

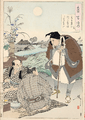

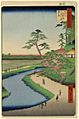

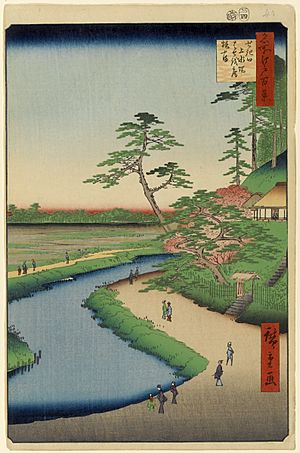

Bashō was shown in a ukiyo-e woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. This was part of the One Hundred Aspects of the Moon collection. His hermitage was also shown by Hiroshige in the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo collection.

Modern Views of Bashō's Poetry

People continued to study Bashō's poems in the 1900s. His poems were also translated into many languages around the world. In Western countries, Bashō is seen as the best haiku poet. This has made his poetry very important. Westerners often prefer haiku over other Japanese poem forms. Some Western scholars even think Bashō invented haiku. Bashō's simple and vivid poems greatly influenced poets like Ezra Pound and the Beat Generation.

A researcher named Jaime Lorente studied Bashō's hokku. He found that about 15% of Bashō's poems did not perfectly fit the 5-7-5 syllable pattern. This shows that Bashō sometimes broke the traditional rules.

In 1942, the Haiseiden building was built in Iga, Mie. This was to celebrate 300 years since Bashō's birth. The building has a round roof like a "traveler's umbrella." It was made to look like Bashō's face and clothes.

Two of Bashō's poems became popular in a short story. It was called "Teddy" by J. D. Salinger. It was published in 1952.

In 1979, a crater on the planet Mercury was named after him.

In 2003, a film called Winter Days was made. It used Bashō's 1684 renku collection. Different animators created a series of animations for the film.

List of Works

- Kai Ōi (The Seashell Game) (1672)

- Edo Sangin (江戸三吟) (1678)

- Inaka no Kuawase (田舎之句合) (1680)

- Tōsei Montei Dokugin Nijū Kasen (桃青門弟独吟廿歌仙) (1680)

- Tokiwaya no Kuawase (常盤屋句合) (1680)

- Minashiguri (虚栗, "A Shriveled Chestnut") (1683)

- Nozarashi Kikō (The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton) (1684)

- Fuyu no Hi (Winter Days) (1684)*

- Haru no Hi (Spring Days) (1686)*

- Kawazu Awase (Frog Contest) (1686)

- Kashima Kikō (A Visit to Kashima Shrine) (1687)

- Oi no Kobumi, or Utatsu Kikō (Record of a Travel-Worn Satchel) (1688)

- Sarashina Kikō (A Visit to Sarashina Village) (1688)

- Arano (Wasteland) (1689)*

- Hisago (The Gourd) (1690)*

- Sarumino (猿蓑, "Monkey's Raincoat") (1691)*

- Saga Nikki (Saga Diary) (1691)

- Bashō no Utsusu Kotoba (On Transplanting the Banana Tree) (1691)

- Heikan no Setsu (On Seclusion) (1692)

- Fukagawa Shū (Fukagawa Anthology)

- Sumidawara (A Sack of Charcoal) (1694)*

- Betsuzashiki (The Detached Room) (1694)

- Oku no Hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Interior) (1694)

- Zoku Sarumino (The Monkey's Raincoat, Continued) (1698)*

- * Denotes the title is one of the Seven Major Anthologies of Bashō (Bashō Shichibu Shū)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Matsuo Bashō para niños

In Spanish: Matsuo Bashō para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |