Max Fleischer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Max Fleischer

|

|

|---|---|

Fleischer in 1919

|

|

| Born |

Majer Fleischer

July 19, 1883 |

| Died | September 25, 1972 (aged 89) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1918–1962 |

| Known for | Creation of Betty Boop, invention of the rotoscope and the "follow the bouncing ball" technique |

|

Notable work

|

Animated Antics Betty Boop Color Classics Out of the Inkwell Popeye the Sailor Talkartoons Screen Songs Song Car-Tunes Stone Age Cartoons first Superman animated work |

| Spouse(s) | Ethel "Essie" Goldstein (died 1988) |

| Children | Richard Fleischer (son) Ruth Fleischer (daughter) |

| Relatives | Dave Fleischer (brother) Lou Fleischer (brother) Seymour Kneitel (son-in-law) |

Max Fleischer (born Majer Fleischer; July 19, 1883 – September 25, 1972) was an American animator, inventor, film director, and film producer. He also started and owned his own studio. Born in Kraków, he moved to the United States. Max Fleischer was a pioneer in making animated cartoons. He led Fleischer Studios, which he started with his younger brother, Dave Fleischer.

He brought famous characters like Koko the Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman to the movie screen. He also created several important inventions for animation. These include the rotoscope, the "follow the bouncing ball" technique (first used in the Ko-Ko Song Car-Tunes films), and the "stereoptical process". His son, Richard Fleischer, became a film director.

Early Life and Beginnings

Max Fleischer was born on July 19, 1883, in Kraków, which was then part of Austria-Hungary. His family was Jewish. He was the second of six children. His father, Aaron Fleischer, was a tailor. The family moved to the United States in March 1887 and settled in New York City.

Max went to public school and later attended evening high school. He studied commercial art at Cooper Union and fine art at the Art Students League of New York. He also went to the Mechanics and Tradesman's School.

Fleischer started his career at The Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper. He began as an errand boy and worked his way up to photographer and then staff cartoonist. He drew editorial cartoons and later full comic strips. During this time, he met John Randolph Bray, a newspaper cartoonist and early animator, who later helped him get into animation.

In 1905, Fleischer married Ethel (Essie) Goldstein. He worked as a technical illustrator and later as an art editor for Popular Science magazine.

Career in Animation

The Rotoscope Invention

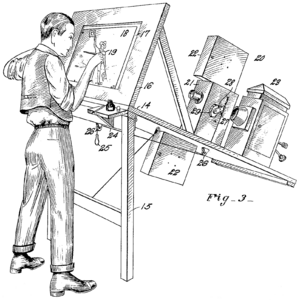

Around 1914, animated cartoons started appearing in movie theaters. However, they often looked stiff and jerky. Max Fleischer invented a way to make animation smoother. He created a device called the rotoscope. This machine combined a projector and an easel. It allowed animators to trace images from live-action film footage. This invention helped Fleischer create more realistic animation. He received a patent for the rotoscope in 1917.

Early Animation Work

Max Fleischer got his first chance to produce films at the Pathé Exchange. He chose to make a political cartoon about a hunting trip by Theodore Roosevelt. After this, he worked with John R. Bray at Paramount. Bray had a deal to distribute films with Paramount.

During World War I, Max Fleischer was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. There, he produced some of the first Army training films. These films taught soldiers about things like reading maps and using weapons. After the war, Fleischer returned to making films for theaters and educational purposes.

The Inkwell Studios and Koko the Clown

Fleischer created his Out of the Inkwell film series. These films featured a character called "The Clown," who was based on his brother Dave's experience as a sideshow clown. The series first appeared from 1919 to 1921.

Out of the Inkwell was special because it combined live action with animation. Max Fleischer himself would appear as an artist who drew the clown figure from an ink bottle onto his drawing board. This clever mix of live action and realistic animation made his series unique.

In 1921, Max and Dave started their own company, Out of the Inkwell Films, Incorporated. In 1924, "The Clown" character was given a name: "Ko-Ko." An animator named Dick Huemer helped redesign Ko-Ko and created his dog friend, Fitz. Huemer also helped the Fleischers rely less on the rotoscope for every animation. Max Fleischer also invented the "inbetweener" position. This meant one animator would draw the main poses, and an assistant would fill in the drawings in between. This made animation production faster and was soon used by the whole industry.

Fleischer also developed a technique called rotoscoping (also known as "aerial image photography"). This allowed animators to photograph animation drawings with live-action film to create a combined image. This method was very useful for making titles and special effects.

Besides comedy films, Fleischer also made educational films. In 1923, he created two longer films that explained Albert Einstein's Theory of Relativity and Charles Darwin's Evolution using animation and live action.

The Bouncing Ball and Sound Cartoons

In 1924, Fleischer partnered with others to form Red Seal Pictures Corporation. During this time, Fleischer invented the "Follow the Bouncing Ball" technique. This was used in his Ko-Ko Song Car-Tunes series. In these films, song lyrics appeared on screen, and an animated ball bounced over the words to show when to sing them.

Some of these Song Car-Tunes were among the first cartoons to use synchronized sound. The film My Old Kentucky Home (1926) used sound-on-film technology. This was actually before Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie (1928), which is often mistakenly called the first cartoon with synchronized sound. The Song Car-Tunes series ended in 1927 when the Red Seal company went bankrupt.

After this, Fleischer started working with Paramount. His Out of the Inkwell series was renamed The Inkwell Imps. In 1929, Fleischer formed a new company, Fleischer Studios, Inc.

Fleischer Studios, Inc.

Fleischer Studios began making industrial films, like Finding His Voice (1929), which showed how sound recording worked. He also started producing a new version of the "Song Car-tunes" called Screen Songs, which had sound.

Max Fleischer continued to invent new devices to improve sound recording for films. These inventions helped make sure that the music and dialogue in his cartoons were perfectly timed.

Betty Boop's Rise to Fame

Max Fleischer's famous character, Betty Boop, first appeared as a small part in an early Talkartoon called Dizzy Dishes (1930). She was inspired by singer Helen Kane. Betty Boop started as a mix between a poodle and a human. She became so popular that Paramount encouraged Fleischer to make her a regular character. She was later changed into a fully human female and became Fleischer's most famous creation.

The "Betty Boop" cartoon series began in 1932 and was a huge success. Helen Kane later sued Fleischer, claiming Betty Boop was a copy of her. However, the court found that Kane did not invent the "baby" style of singing, and she lost the lawsuit.

Popeye the Sailor's Popularity

One of Fleischer's best business decisions was getting the rights to the comic strip character Popeye the Sailor. Popeye first appeared in a Betty Boop cartoon short called Popeye the Sailor (1933). Popeye became one of the most successful comic strip characters ever adapted for the screen. The Fleischer Studio's unique style and use of music helped make Popeye so popular. By the late 1930s, Popeye was even more popular than Mickey Mouse!

Working with Paramount

In the mid-1930s, Fleischer Studios was very busy. They were making four different cartoon series: Betty Boop, Popeye, Screen Songs, and Color Classics. This meant they released 52 cartoons every year. Fleischer's studio supplied these cartoons to Paramount's theaters.

Fleischer was interested in color animation. At first, Paramount's financial problems meant he couldn't use the best three-color Technicolor process. This allowed Walt Disney to get exclusive rights to it for a few years. So, Fleischer used two-color processes like Cinecolor for his first Color Classics. The first color cartoon, Poor Cinderella (1934), starred Betty Boop. By 1936, Disney's exclusive deal ended, and Fleischer could use the three-color Technicolor process for films like Somewhere in Dreamland.

Fleischer also used his "Stereoptical Process" in these color cartoons. This technique used 3D model sets instead of flat backgrounds. The animation drawings were then filmed in front of these models, creating a sense of depth. This was used greatly in the longer Popeye cartoons like Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor (1936) and Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba's Forty Thieves (1937). These showed Fleischer's interest in making animated feature films.

After Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs became a huge hit in 1938, Paramount decided they wanted Fleischer to make an animated feature film too.

Challenges and Changes

The huge popularity of Popeye cartoons meant the studio had to expand quickly and work faster. This led to crowded conditions. In May 1937, Fleischer Studios faced a five-month strike. This meant their cartoons weren't shown in theaters for a while. Max Fleischer felt this personally, and it caused him stress. After the strike, Max and Dave Fleischer decided to move the studio from New York City to Miami, Florida, hoping for more space and fewer labor issues.

Once in Miami, the relationship between Max and Dave started to get difficult, especially with the pressure to deliver their first feature film.

Their first feature film was Gulliver's Travels, based on the classic novel. The film cost more than expected, but it earned a good profit for Paramount. However, Fleischer Studios was penalized for going over budget, which caused financial difficulties for the studio.

In 1940, Max focused more on business and technical inventions. He developed new ways to transfer drawings onto animation cels, which saved a lot of time. That same year, Fleischer acquired the rights to Superman and started developing the Superman animated series. These cartoons were more serious and had science fiction elements, which interested Max.

Paramount then ordered a second feature film, Mr. Bug Goes to Town. This film was technically very good. It was supposed to be released for Christmas 1941, but the attack on Pearl Harbor happened just two days after its preview, and the release was canceled.

After this, Max Fleischer was asked to resign from his studio. His brother Dave had already resigned. Paramount took over the studio, and its name officially changed to Famous Studios in May 1942. Max's son-in-law, Seymour Kneitel, became one of the new managers.

Later Years and Legacy

After leaving his studio, Max Fleischer worked for The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit, Michigan. He led their animation department, producing training films for the Army and Navy during the war. He also worked on top-secret research for the war effort. In 1944, he wrote a book called Noah's Shoes, which was a story about building and losing his studio.

After the war, he supervised the animated film Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1948). In 1953, Fleischer returned to the Bray Studios in New York.

In 1954, Max's son, Richard Fleischer, was directing 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea for Walt Disney. This led to a meeting between Max and Walt Disney, and Max also saw many former Fleischer animators who were now working for Disney.

In 1955, Fleischer won a lawsuit against Paramount because his name had been removed from the credits of his films. In 1958, Fleischer brought back Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc. He worked with his former animator Hal Seeger to produce 100 new color Out of the Inkwell cartoons for television.

Max Fleischer and his wife Essie moved to the Motion Picture Country House in 1967. Max Fleischer passed away on September 25, 1972, at the age of 89. He was called the "dean of animated cartoons" by the press.

After his death, there was a renewed interest in his work. Films like The Betty Boop Scandals of 1974 and The Popeye Follies brought his classic cartoons back to theaters. This led to new research and appreciation for Max Fleischer's unique animation style, which was seen as an alternative to Walt Disney's.

See also

In Spanish: Max Fleischer para niños

In Spanish: Max Fleischer para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |