May Howard Jackson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

May Howard Jackson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

May Howard

7 September 1877 Philadelphia, PA

|

| Died | 12 July 1931 (aged 53) New York, NY

|

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

| Known for | Sculpture |

|

Notable work

|

Portrait Bust of Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1919)

|

| Spouse(s) | William Sherman Jackson |

| Awards | Harmon Foundation, 1928 |

May Howard Jackson (born September 7, 1877 – died July 12, 1931) was an important African American sculptor and artist. She was active during the New Negro Movement, a time when Black artists, writers, and musicians created amazing works. May Howard Jackson was well-known in Washington, D.C. for her art from 1910 to 1930.

She was one of the first Black sculptors to use America's racial challenges as a theme in her art. Her sculptures showed mixed-race people with dignity. Her own experiences as a multiracial person influenced her work.

Contents

Early Life and Education

May Howard was born in Philadelphia on September 7, 1877. Her parents, Floarda and Sallie Howard, were a middle-class couple.

Learning Art

May attended J. Liberty Tadd's Art School in Philadelphia. This school taught art in new and creative ways. The founder, Tadd, believed that art training was important for strengthening the brain. He even encouraged students to use both hands for drawing. May learned drawing, designing, modeling, and carving at this school.

She later received a full scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1895. She was the first African American woman to attend PAFA. She studied with famous artists like William Merritt Chase and Charles Grafly. Her art from this time showed a natural and detailed style.

Another artist, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, who was also at PAFA, invited May to study art in France. But May declined. She believed it was not necessary to travel to Europe to improve her art. After four years at PAFA, May Howard married William Sherman Jackson. He was a math teacher who later became a high school principal.

Life in Washington, D.C.

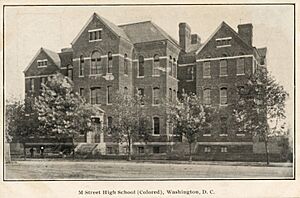

By 1902, May and William Jackson lived in Washington D.C. William taught at the M Street High School. This was the first public high school for African Americans in the United States. It was a top school for Black students at the time. Many teachers there were highly educated.

During this time, there was a big debate about the future of Black education. Booker T. Washington believed Black Americans should focus on learning skills for jobs. He thought this would help them succeed in the economy. On the other side was W. E. B. Du Bois. He was a leader of the New Negro Movement and helped start the NAACP. Du Bois argued that Black Americans deserved the right to vote, equal rights, and education based on their abilities.

The M Street High School was part of this debate. Its principal, Anna J. Cooper, invited Du Bois to speak. He spoke against vocational training being the only option for Black Americans. This caused some trouble for Dr. Cooper. In 1906, May's husband, William, became the principal. May also taught Latin there. The Jacksons played a key role in keeping M Street High School excellent. This gave them a strong reputation in the Black community.

Art Career

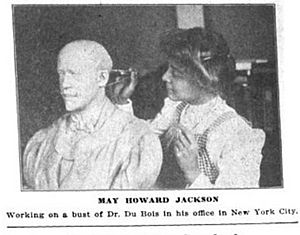

After moving to Washington, May Jackson wanted to study at the art school connected to the Corcoran Gallery of Art. But she was not allowed in because she was Black. This made her feel discouraged for a while. However, W. E. B. Du Bois encouraged her to continue her art. He believed her talent could inspire her people.

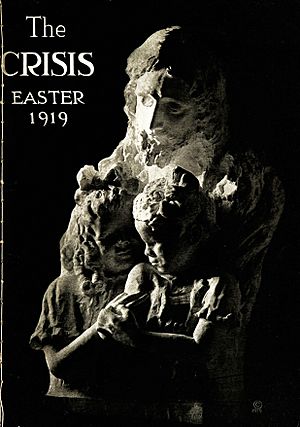

Du Bois not only supported her personally but also featured her art in The Crisis. This was his journal and the official magazine of the NAACP.

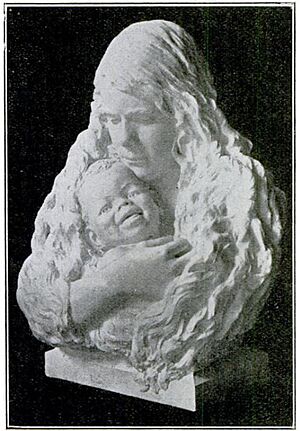

With this support, Jackson became known for using racial themes in her art. She created dignified sculptures of Black leaders. She also made touching sculptures of mothers and their mixed-race children. These works became famous in her exhibitions for the next two decades.

Jackson sculpted Du Bois in 1907. Du Bois also helped her by publishing news about her exhibitions in The Crisis until her death in 1931.

Public Art Shows

Washington Art Scene

In 1912, Jackson showed her sculpture of Du Bois at the Veerhoff Gallery in Washington. The Washington Star newspaper gave her a good review. They praised her work for showing life and movement. Later, they also praised her sculpture of Assistant Attorney General William H. Lewis. The newspaper said her portraits captured the person's character.

In 1916, she showed more sculptures at Veerhoff. The Star newspaper again praised her "exceptional gift." It was hard for Black artists to find places to show their work in Washington. The fact that Jackson's art was displayed showed her great talent.

In 1917, Jackson even exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. This was the same art school that had rejected her years before because of her race. This event was big news across the United States. Newspapers called it the "First Recognition for the Race."

Special Exhibitions

Because it was hard to get into regular galleries, artists like Jackson found other places to show their work. In May 1919, she had a solo show of 25 sculptures at the Y.M.C.A. in Washington, D.C.

The M Street High School moved to a new building in 1916. It was renamed Dunbar School after the famous African-American poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar. Jackson later made a bronze sculpture of Dunbar for the school. Dunbar High School started the Tanner Art League in 1919. They tried to have an annual art show for Black artists. Jackson's work was included in these shows. Her sculpture, The Brotherhood, was shown at Dunbar in 1922. It had also been shown at a big exhibition in New York.

Teaching Art

Jackson had a sculpture studio in her home in Washington. She also taught art at Howard University for two years (1922-1924). She taught and influenced James Porter, who later wrote one of the first histories of African-American art.

Getting Recognized

During this time, racial segregation was common in the South. Topics like mixed-race people were often avoided. Laws against mixed-race marriages were even suggested in some places.

Despite these challenges, Jackson's work was recognized. She received a Harmon Foundation Award in 1928. This award was important because it was one of the first national prizes for Black artists. An art historian, Leslie King-Hammond, praised Jackson for showing issues of race and class without being overly emotional.

Even with this recognition, Jackson felt she had not achieved enough. In 1929, she wrote about a "deep sense of injustice" that had followed her throughout her life.

Race and Identity in Art

May Jackson had light skin and could sometimes be mistaken for a white person. But the racial issues of the early 1900s pushed her to focus on her Black identity. She even shared details about her family's racial background with an anthropologist.

Her own experiences with racism continued. After showing her work at the National Academy of Design in 1916 and 1918, they asked if she had "Negro blood." When she said yes, they stopped showing her work.

Jackson was fascinated by the many different appearances among African Americans. She showed this in her sculptures like "Shell-Baby in Bronze" (1914) and "Mulatto Mother and Child" (1929). These pieces explored her own racial identity.

Her unique style was bold for its time. She focused on honest portraits of children, family members, and important African Americans. Many galleries were not interested in these subjects at first. It was not until the Harmon Foundation Awards began in 1926 that there was a national prize for Black artists.

Jackson's racial identity was clear. She was listed as one of the Black women in the March 13, 1913, women's suffrage parade.

Later Years and Legacy

The Harmon Foundation art shows happened around the time of the Great Depression. This was a difficult economic period. May Howard Jackson died in 1931. After her death, her work was not widely known for a while. Some art critics were uncomfortable with her portrayal of racial ambiguity.

Lasting Impact

Jackson and her husband took in her nephew, Sargent Claude Johnson, when he was fifteen. His parents had passed away. Johnson later became a famous sculptor during the Harlem Renaissance. He first learned about sculpture from his aunt's work and studio.

May Howard Jackson is buried at the Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about her death in The Crisis magazine. He said that the challenges of the "Color Line" (racial discrimination) deeply affected her soul.

May Howard Jackson was an artist who pushed boundaries. Her unique vision and American training helped her create a powerful body of work. She is now recognized as an important American sculptor.

Exhibitions

Public Shows

- The Veerhoff Gallery, Washington D.C. (1912, 1916)

- The New York Emancipation Exhibition (1913)

- The Corcoran Art Gallery (1915)

- The National Academy of Design (1916)

- May Howard Jackson: 25 Sculptures. War Service and Recreation Center, Y.M.C.A., Washington, D.C. (May 1919)

- Exhibit of Fine Arts by American Negro Artists, The Harmon Foundation, International House, New York (1929)

- An Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by American Negro Artists at the National Gallery of Art (1929)

Posthumous Group Shows

- 3 Generations of African American Women Sculptors: A Study in Paradox (1996) Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, Philadelphia

Catalogued Work

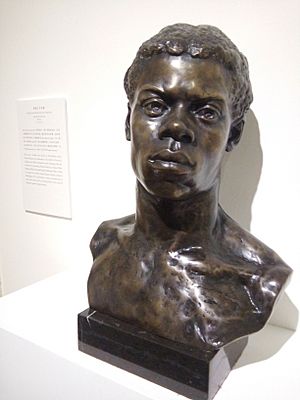

- Slave boy / Portrait Bust of an African (1899) bronze

- Portrait Bust of Paul Lawrence Dunbar (Dunbar High School, Washington D.C.)

- Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar (1906)

- Portrait Bust of W. E. B. Du Bois (1912)

- Assistant Attorney General WIlliam H. Lewis (1912)

- Morris Heights, New York City (1912) oil on linen

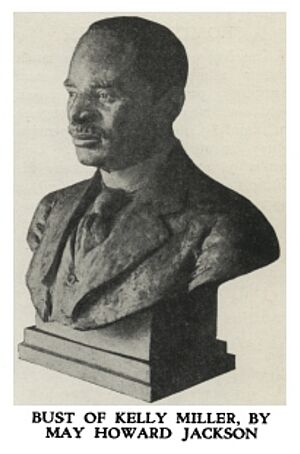

- Portrait Bust of Dean Kelly Miller (1914) bronze

- Shell-baby, bronze (1915, exhibited 1929)

- Head of a Negro Child (1916)

- William H. Lewis (before 1919)

- William Stanley Braitewait (before 1919)

- Portrait Bust of Reverend Francis J. Grimke (1922)

- Suffer Little Children to Come Unto Me (no date)

- Bust of a Young Woman (no date, plaster)

- Mulatto Mother and her Child / Mother and Child, plaster (exhibited 1918)

- William Tecumsah Sherman Jackson (exhibited 1929)

- Negro Dancing Girl (exhibited 1929)

- Resurrection (exhibited 1929)

Awards

- Harmon Foundation Award in the Fine Arts (1928) Bronze Medal

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |