Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

|

|

|---|---|

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller in 1910

|

|

| Born |

Meta Vaux Warrick

June 9, 1877 |

| Died | March 13, 1968 (aged 90) |

| Education | University of the Arts, College of Art and Design, Académie Colarossi, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Occupation | Sculptor, painter, poet |

| Movement | Harlem Renaissance |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | William H. Warrick Emma Jones |

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (MEE-tə-_-vow; born Meta Vaux Warrick; June 9, 1877 – March 13, 1968) was an African-American artist. She was famous for celebrating themes about African heritage and culture. Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was a key artist during the Harlem Renaissance. She was known as a poet, painter, theater designer, and a sculptor who showed the experiences of Black Americans.

Around the year 1900, she became known as the first Black woman sculptor. She was also a well-known sculptor in Paris before she came back to the United States. A famous sculptor named Auguste Rodin mentored her. People have called her "one of the most imaginative Black artists of her generation." Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller used her art to talk about the unfairness faced by African Americans. She created powerful sculptures that showed important moments of racial injustice, like the sad story of Mary Turner.

Contents

Early Life & Art Beginnings

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 9, 1877. Her parents were Emma (née Jones) Warrick and William H. Warrick. Emma was a skilled wig maker and beautician for wealthy white women. William was a successful barber and caterer. Her father owned several barber shops, and her mother had her own beauty salon.

Meta was named after Meta Vaux, the daughter of Senator Richard Vaux, who was one of her mother's customers. Her family was well-respected in the African-American community. They had a special place in society because of their talents. In Philadelphia, many free Black people found it hard to get good jobs. Only a few could become ministers, doctors, barbers, teachers, or caterers. Even with racism and laws like Jim Crow laws during the Reconstruction era, Meta's parents found success. They lived in a lively African-American community in Philadelphia.

Because her parents were successful, Meta had many chances to learn and experience culture. She studied art, music, dance, and horseback riding. Her older sister, Blanche, who also studied art, helped Meta start her art journey at home. Meta's father, who liked sculpture and painting, took her to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her sister, who later became a beautician, saved clay for Meta to use for her art.

In 1893, Meta went to Girls' High School in Philadelphia. There, she studied art and other school subjects. She was one of the talented artists chosen from Philadelphia public schools. She studied art and design at J. Liberty Tadd's art program in the early 1890s. Her brother and grandfather told her many exciting stories. These stories helped shape her sculpture. She became known as "the sculptor of horrors" because of her powerful and sometimes intense art style.

Marriage & Family Life

In 1907, Meta Warrick married Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller. He was a well-known doctor and psychiatrist. He was famous for his work on Alzheimer's disease. Dr. Fuller was born in Liberia and was one of the first Black psychiatrists in the United States.

The couple made their home in Framingham, Massachusetts. They were one of the first Black families to live in that community. Meta kept creating art, even though some people thought she should just be a housewife after having children. She and her husband had three children. One of their sons, Perry, also became a sculptor. Important African-American people and even the Prince of Siam visited their home.

Meta Warrick Fuller was active in her community. She helped start and light productions for the Framingham Dramatic Society. She was also a member of St. Andrew's Episcopal Church. There, she directed and designed costumes for plays and pageants.

After a fire in 1910, Meta Warrick Fuller built a studio behind her house. Her husband did not like this idea. Between her home duties, she found inspiration in her religion. She began to sculpt traditional biblical scenes. Meta believed making art was her special calling. Being told not to create art did not stop her.

Dr. Fuller passed away in 1953. Meta Warrick Fuller died on March 13, 1968, in Framingham, Massachusetts.

Despite being faced with sexism and racism, Meta’s genius shone throughout her life and work as she carried herself with pride and dignity that is evident in her timeless pieces of art which are now displayed in various places around the U.S.

Art Education & Growth

Meta's art career began when one of her high school projects was chosen for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Because of this work, she won a four-year scholarship in 1894. She went to the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now The University of the Arts). There, her talent for sculpture really grew.

As a young woman artist, Meta did not follow traditional ideas. She sculpted pieces that were influenced by the powerful images of the Symbolist era. She sometimes created literary sculptures and sometimes portrait art. She studied portrait art with Charles Grafly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Even though she said she couldn't focus only on African-American themes, Fuller became one of the best artists to show the Black experience in the United States. In 1898, she earned her diploma and teaching certificate. She also received a scholarship for another year of study.

In 1899, after graduating, Meta Warrick traveled to Paris, France. She studied sculpture and anatomy at the Académie Colarossi. She also studied drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, she faced racial discrimination. The American Women's Club refused her a room, even though she had a reservation. An African-American painter, Henry Ossawa Tanner, who was a family friend, helped her find a place to stay. He also introduced her to his group of friends.

Meta's art became stronger in Paris, where she studied until 1902. She was influenced by the famous sculptor Auguste Rodin. She became very good at showing human feelings in her art. The French press called her "the delicate sculptor of horrors." In 1902, she became Rodin's student. Rodin saw her plaster sketch called Man Eating His Heart. He told her, "My child, you are a sculptor; you have the sense of form in your fingers."

Art Career & Exhibitions

Meta Warrick created art about the African-American experience that was groundbreaking. Her works explored ideas about nature, religion, identity, and nation. She is considered part of the Harlem Renaissance. This was a time when many African Americans in New York created amazing art, literature, plays, and poetry. The Danforth Museum says that Fuller is "generally considered one of the first African-American female sculptors of importance."

Paris Exhibitions

In Paris, she met W. E. B. DuBois, an American sociologist. He became a lifelong friend and encouraged Warrick to use African and African-American themes in her art. She also met French sculptor Auguste Rodin, who supported her sculpting. Her main mentor was Henry Ossawa Tanner.

The "strong and powerful" nature of her sculptures drew French crowds to her work. They were amazed that a woman could create art that showed such deep feelings. It was a relief for Meta that her gender did not stop people from liking her art about race. By the end of her time in Paris, she was well-known. Her works were shown in many galleries.

Samuel Bing, a supporter of famous artists, recognized her talent. He sponsored a solo exhibition for her at his Salon de l'Art Nouveau. In 1903, just before Meta returned to the United States, two of her works, The Wretched and The Impenitent Thief, were shown at the Paris Salon.

Art in the United States

When Meta returned to Philadelphia in 1903, some people in the art world avoided her because of her race. Also, her art was sometimes seen as "domestic." However, Fuller became the first African-American woman to get a U.S. government art project. For this, she created a series of scenes showing African-American history. These were for the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1907.

Her display included fourteen dioramas (small scenes with figures) and 130 painted plaster figures. They showed scenes like slaves arriving in Virginia in 1619 and the home lives of Black people.

Mary Turner was her response to the sad event in 1918 where a young, pregnant Black woman was killed in Lowndes County, Georgia. Fuller's friend, Angelina Weld Grimké, wrote a short story based on this event. Meta Warrick also worked for women's rights. She joined the Women's Peace Party and the Equal Suffrage Movement. But she stopped when she realized Black women were not included in the fight for equal voting rights. She often sold her art to help fund campaigns to register voters in the South.

Warrick showed her art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 1906 and again in 1908. In 1910, a fire at a warehouse in Philadelphia destroyed many of her works. She lost 16 years of her art, including paintings and sculptures. Only a few early pieces stored elsewhere were saved. This loss was very hard for her.

1907 Jamestown Tercentennial

In February 1907, Meta Warrick signed a contract to create 14 dioramas. These showed the African-American experience. At the time, it was called the "Historic Tableaux of the Negroes' Progress." A historian named W. Fitzhugh Brundage said Fuller's scenes showed "the wide range of Black abilities, hopes, and experiences." They offered a clear different view from white history.

Warrick's scenes were shown prominently in the Negro Building at the Jamestown Tercentennial. They took up a large space. Each scene had painted plaster figures and detailed painted backgrounds. The 14 scenes showed: the arrival of the first slaves at Jamestown; slaves working in a cotton field; a runaway slave hiding; a meeting of the first African Methodist Episcopal Church; a slave defending his owner's home during the Civil War; newly freed slaves building their own home; an independent Black farmer, builder, and contractor; a Black businessman and banker; scenes inside a modern African-American home, church, and school; and finally, a college graduation. For her work on these scenes, Warrick received a gold medal from the exposition directors.

Ethiopia and Later Works

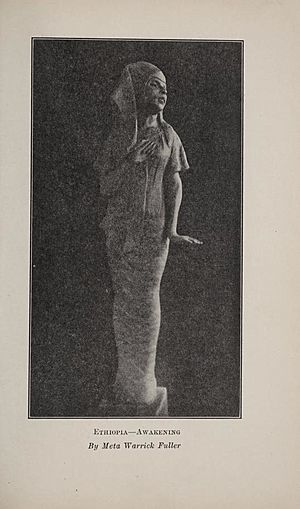

Fuller showed her art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1920. She created one of her most famous works, Ethiopia (also known as Ethiopia Awakening), for the America's Making Exhibition in 1921. This event aimed to show how immigrants contributed to U.S. art and culture. This sculpture was in the exhibition's "colored section." It represented a new Black identity that was growing during the Harlem Renaissance. It showed the pride of African Americans in their African heritage and identity.

Ethiopia was inspired by Egyptian sculptures. It is a sculpture of an African woman coming out of a mummy's wrappings, like a chrysalis from a cocoon. This showed her message about Black awareness around the world. Fuller made several versions of Ethiopia.

In 1922, Fuller showed her sculptures at the Boston Public Library. Her work was also part of an exhibition for the Tanner League. This show was held at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C.. Government art projects kept her busy, but she did not get as much encouragement in the U.S. as she had in Paris. Fuller continued to show her work until her last exhibition in 1961 at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Poetry & Theater Contributions

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was also a poet. Her poem "Departure" was included in a 1991 book called Now is Your Time! The African-American Struggle for Freedom.

- The time is near (reluctance laid aside)

- I see the barque afloat upon the ebbing tide

- While on the shores my friends and loved ones stand.

- I wave to them a cheerful parting hand,

- Then take my place with Charon at the helm,

- And turn and wave again to them.

- Oh, may the voyage not be arduous nor long,

- But echoing with chant and joyful song,

- May I behold with reverence and grace,

- The wondrous vision of the Master's face.

Theater Work

Warrick Fuller made important contributions to theater. She was a talented designer, director, and actress. One of her main interests was stage lighting. This was not seen as a true art form until the late 1920s, and men mostly did lighting design. Fuller was able to design for both African-American and white theater groups, which was very rare at the time.

In 1918, she joined theater groups in Boston, Massachusetts. She was known for her "living pictures" (where people pose to create a scene). She also made props, scenery, and masks. For an African-American play called The Answer, Fuller designed costumes and had a small acting role. She became active in the Civic League Players (CLS) in the late 1920s. She was the only African-American in that group. With the CLS, Fuller worked on over thirty shows in many different areas of production. She also taught workshops.

In 1928, she took theater classes at Wellesley College and Columbia University. These classes focused on pageants, lighting, and writing plays. After being less active with the CLS, Fuller joined a Black theater company called the Allied Arts Theatre Group (AATG). There, she worked as a head designer, director, and board member. She was involved with the AATG until the founder passed away in 1936. Even with her busy life as an artist and theater worker, Fuller wrote at least six plays. She used the pen name Danny Deaver. Here is a small part of the stage directions from her play, A Call After Midnight:

"On the long hall table is a lamp, which the characters snap on and off, as they stop to look for mail, which is left in a receptacle for that purpose. The wall lights of the room are controlled by a switch at right of entrance, but these are of dull amber, the candle variety, the light is never bright."

Legacy & Collections

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller's work has gained new attention since the late 1900s. Her art was shown in a traveling exhibition in 1988 at the Crocker Art Museum. Other artists like Aaron Douglas, Palmer C. Hayden, and James Van Der Zee were also featured. Her work was also part of a traveling exhibition called Three Generations of African American Women Sculptors: A Study in Paradox, in Georgia in 1998.

The Danforth Museum has a large collection of Fuller's sculptures. This includes many unfinished works from her home studio. Many of these were shown in a special exhibition of her work from November 2008 to May 2009.

Fuller's art was also included in the 2015 exhibition We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s at the Woodmere Art Museum.

Famous Works

- Bacchante, painted plaster sculpture, 1930

- Emancipation, in plaster, 1913; in bronze, 1999. Featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

- Ethiopia, small sculpture, painted to look like bronze, c. 1921. It is at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- Ethiopia Awakening, bronze sculpture, greenish-black color, c. 1921. It is at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

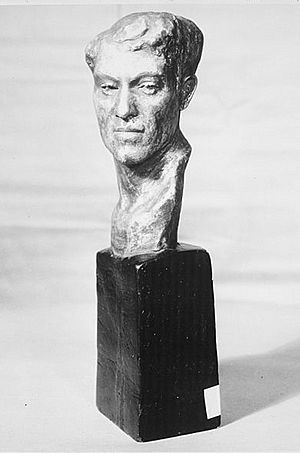

- Henry Gilbert, painted plaster sculpture, 1928

- Jason, painted plaster sculpture, Danforth Museum

- La petite danseuse, bronze sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Les Miserables, bronze sculpture, Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington

- Lazy Bones in the Shade, sculpture, c. 1937

- Man Eating Out His Heart, painted plaster sculpture, 1905–1906.

- Mary Turner (A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence), painted plaster sculpture, 1919, Museum of Afro-American History, Boston, Massachusetts

- Mother and Child, cast bronze sculpture, 1962, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War, c. 1917. Renamed and shown as "Ravages of War" in 1999 at West Virginia State College.

- Phyllis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784), painted plaster sculpture, c. 1925. It was made from an old picture published in 1773.

- Refugee, sculpture, c. 1940. A hunched male figure with a cane.

- Talking Skull, bronze sculpture, 1937, Museum of Afro-American History, Boston, Massachusetts. A kneeling male figure facing a skull.

- The Good Shepherd, painted plaster sculpture, c. 1926–1927

- Waterboy, sculpture, 1930

Images for kids

-

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (around 1895)

-

Meta V.W. Fuller (1877–1968). One of the leading Black female sculptors in America. She lived here, studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, later with Auguste Rodin in Paris. Her sculpture depicted human suffering. (Historical Marker at 254 S. 12th St. Philadelphia PA - Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 1991)

See Also

In Spanish: Meta Warrick Fuller para niños

In Spanish: Meta Warrick Fuller para niños