Mesta facts for kids

The Mesta (which means "Honorable Council of the Mesta" in Spanish) was a very strong group that protected livestock owners and their animals in the old Crown of Castile in Spain. It started in the 1200s and ended in 1836. The Mesta is most famous for organizing the yearly journeys of sheep, especially the Merino breed. These sheep moved from summer pastures to winter pastures and back again.

The kings of Castile gave the Mesta and its animals special protection, calling them the Cabaña Real (meaning "royal flock"). The Mesta also received many other special rights. For example, the cañadas (traditional paths for sheep) were legally protected forever. No one could build on them, farm them, or block them. The most important cañadas were called cañadas reales (royal paths) because kings created them.

The Mesta grew as sheep farming became more popular after Castile took over the city of Taifa of Toledo. At first, monasteries, military groups, and rich city people were given rights to use winter pastures. These groups could not grow many crops in the dry lands of New Castile, so they focused on raising animals.

At first, the Mesta included both large and small animal owners. But later, kings started appointing royal officials to its governing body. These officials were often important nobles or church leaders, not always animal owners themselves. Wool exports became very important, especially high-quality merino wool. The Mesta helped its members get rich from this trade by getting them tax breaks. The most important places for selling wool were Burgos, Medina del Campo, and Segovia.

Even today, some streets in Madrid are still part of the cañada system. Sometimes, people even lead sheep through the modern city. This reminds everyone of the old traditions and rights, even though sheep are usually moved by train now.

Contents

How the Mesta Started

The Mesta received its first official royal document from Alfonso X of Castile in 1273. But this document said it was replacing four older ones. So, the Mesta probably existed before 1273. The king's document mostly gave the Mesta royal protection from local taxes and rules.

The Mesta's rights were similar to those of medieval merchant guilds. But the Mesta was more of a protection group. It helped sheep owners with their business. It did not own sheep or pastures itself. It also did not buy or sell wool, or control markets. Its close ties to the Spanish government gave it a very special and widespread role.

The number of sheep in Castile and León grew a lot in the 1100s and early 1200s. There wasn't enough local grass, so shepherds started moving their sheep to pastures further away. This often caused arguments between shepherds and local people. In 1252, laws were made to control how much money could be charged for sheep moving through an area. These laws also protected the use of streams and sheep paths. In 1269, the king put a tax on migrating flocks. By recognizing the Mesta in 1273, King Alfonso could collect more money from the sheep industry.

The word mesta might come from the Latin word mixta, meaning "mixed." This could refer to how stray animals got mixed with other flocks. Another idea is that it comes from mechta, a word used by Algerian nomads for their winter sheep camps. This word might have been used for meetings of animal owners and later for the Mesta itself.

The word mestengo (now mesteño) meant animals whose owner was unknown, literally "belonging to the mesta." In North America, wild horses became known as mesteños, which is where the English word mustang comes from.

Sheep Journeys Before the Mesta

Land and Climate

Most of central Spain has low rainfall. In medieval times, many areas could not grow crops easily. So, raising animals was very important. Small flocks of sheep and goats could be moved to summer pastures near towns. But large numbers of animals were often killed in the autumn because there wasn't enough food in the dry summers and cold winters. There is no clear proof of very large sheep migrations before the late Middle Ages.

As the Christian kingdoms expanded south, they moved into drier areas. In Muslim areas, people used clever ways to manage water and grow crops that could handle dry weather. But Christians did not use these methods until they conquered those lands.

Early Migrations

Some people thought that during the Reconquista (the Christian reconquest of Spain), the lands between Christian and Muslim areas were empty and used mostly for grazing. They believed this encouraged sheep to move around a lot. However, Christian farmers actually settled the Duero valley densely, growing crops and raising small numbers of animals. Large-scale sheep migrations became more common only when the reconquest moved into lands that were not good for farming.

Before the 1100s, farmers in Christian lands mostly raised oxen, cows, pigs, and some sheep. There is no proof of very large sheep flocks or long-distance migrations before the early 1100s. Long-distance sheep journeys in other countries were often for selling wool and collecting taxes, not just for feeding families.

Sheep were not very important in the Islamic Caliphate of Córdoba. There are no records of long-distance migrations before it fell in the 1030s. Some believe that a group called the Marinids brought new sheep breeds and long-distance migration practices from Morocco. But there is no clear proof they brought their flocks to Spain. It is more likely that Moroccan rams were brought to breed with local sheep.

After 1085

When Castile captured Toledo in 1085, its size grew a lot. But its population did not grow as much. Many Muslim people left the southern lands, now called New Castile. Also, new farming tools in the north made it easier to grow grain there. This meant fewer people moved south to farm.

In the 1100s and 1200s, many sheep herders in Old Castile and León started moving their sheep to more distant pastures. This included both normal movements to summer pastures nearby and "inverse" movements to winter pastures further away. For example, many Castilian cities gained control over large areas of mountain pastures and gave their citizens grazing rights.

Monasteries and Military Groups

In early times, most land in Old Castile was owned by peasants who farmed and raised small numbers of animals. But later, much of this land came under the control of monasteries, nobles, and large towns. This change helped large-scale sheep migrations grow. In the 900s and 1000s, some large monasteries started moving their sheep medium distances. They gained royal rights to use pastures in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains.

In the 1200s, military groups like the Order of Santiago and Order of Calatrava gained large land rights in New Castile. They did not settle many farmers on their lands. Instead, they focused on raising animals, especially sheep. Their flocks were among the first to use the cañadas in New Castile. By the late 1100s, these military groups were regularly moving sheep into areas that were still under Muslim control.

The Towns

Kings like Alfonso VIII and Ferdinand III protected the rights of monasteries and military groups to move their sheep south. But Alfonso X realized that giving similar rights to cities and towns in Old Castile would bring in a lot of money. When the Guadalquivir valley was conquered in the 1200s, sheep from the Duero and Tagus areas could spend the winter there. This allowed for longer journeys and more sheep to be fed.

How the Mesta Worked

Organization

The Mesta's rules were updated over time, with important ones made in 1492 and 1511. The Mesta was divided into four main areas called quadrillas (groups). These were based around the main sheep-raising cities in the north: Soria, Segovia, Cuenca, and León. The Mesta's main council had a president, who was always from the Royal Council after 1500, and the leaders of the four quadrillas. The president had a lot of power. For example, in 1779, a reformer named Pedro Rodríguez, Count of Campomanes was appointed president. He worked to break down the Mesta's power by promoting farming in its main winter pasturelands.

Important officials called alcaldes de quadrilla managed the Mesta's laws for its members. There were also financial and legal officials who helped members with leases and arguments.

Anyone who paid membership fees could attend the Mesta's meetings. The fees were based on how many sheep a person owned. Even though every member had one vote, rich nobles and large owners had the most influence. The Mesta usually held two meetings a year: one in the southern pastures in winter and one in the northern centers in autumn. These meetings organized the next sheep migration and elected officials.

Even though important nobles and monasteries were Mesta members, they were not typical. In the 1500s, most sheep owners had small to medium-sized flocks. Two-thirds of the migrating sheep were in flocks of less than 100. By the 1700s, there were fewer small owners, and some owners had more than 20,000 sheep. But the Mesta was still mostly for owners of small to medium flocks. However, in its last century, many small owners stopped migrating unless they worked for large owners. This was because their small flocks were no longer allowed to be grouped together.

The Yearly Migrations

There is not much information about the early migrations. But from the 1500s, the yearly sheep journey was planned carefully. It made sure the Merino sheep had the best conditions for feeding, growing, and having lambs. Moving the sheep to fresh grass all year made their wool very fine. This was used to justify the Mesta's special rights.

From 1436 to 1549, over 2.5 million sheep took part in the yearly migration. This number went down in the 1600s but then rose again in the 1700s, reaching about 5 million sheep by 1790-1795. After the French invasion in 1808, the numbers dropped sharply. In 1832, near the end of the Mesta, it was responsible for 1.1 million migrating Merino sheep.

By the 1700s, there was not enough pasture. So, sheep owners had to arrange grazing leases in advance. They relied on a salaried Mayoral (chief shepherd) to negotiate these leases. Some mayorales cheated, agreeing to high rents and taking a share. But groups of owners called mayoralia helped owners get access to grazing lands.

Most Merino flocks had their home pastures in León, Old Castile, and La Mancha. Flocks from León and Old Castile traveled between 550 and 750 kilometers to their winter pastures. Those from New Castile and La Mancha traveled less than 250 kilometers. The journey south usually took a month or less, arriving in October. They returned north in April and May.

Preparations for the journey south began in mid-September. Each owner's flock, marked with their brand, was given to an experienced mayoral. Larger flocks were kept together but divided into smaller units called rebaños of about 1,000 sheep. Each rebaño had a shepherd and assistants. Shepherds were usually paid with grain, lambs, cheese, and a cash fee. In earlier times, small flocks were grouped into rebaños, but this stopped in the 1700s.

When they arrived at the winter pastures, shepherds checked if the leased lands were good. From the mid-1500s, most owners arranged pastures beforehand. Otherwise, they had to pay high rents for poor grazing land. The rebaños were divided into pens for shelter and lambing. Old or weak sheep and lambs were removed to keep the wool quality high.

Lambs were ready to travel north in the spring. The flocks left the southern plains from mid-April. Their wool was shorn on the way north, then washed and taken to Mesta warehouses. The wool was later sent to markets or ports for shipping to other countries. After shearing, the journey north continued slowly. The last flocks reached their home pastures in May or early June. They would then move to summer pastures in the hills, often tired from the long journey.

The Cañadas (Drove Roads)

The yearly migration was possible because of the cañadas. These are long pathways used by migrating flocks in countries like Spain. Some of these paths in Spain have existed since the early Middle Ages. Before the 1100s, sheep were usually a small part of farming in León and Old Castile. They rarely moved outside their local area. The cañadas in León and Old Castile might have grown from shorter migrations that became longer as Christian lands expanded south.

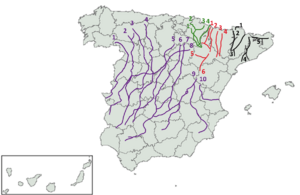

The main north-south cañadas were called Cañadas Reales (Royal Drove Roads). Their exact routes might have changed over time. They were only marked and given a specific width when crossing farmed land. Near their start and end points, many smaller local cañadas joined or branched off from the main ones. There were three main groups of cañadas reales: the western (Leonesa), the central (Segoviana), and the eastern (Manchega). These ran through the cities of León, Segovia, and Cuenca.

There are few records of sheep numbers before the early 1500s. In the 1500s, between 1.7 and 3.5 million Merino sheep migrated each year. The numbers declined in the late 1500s and early 1600s, a time of wars. This was not because there were fewer Merino sheep overall. Instead, fewer sheep made long-distance journeys. More Merino sheep were kept in their home areas.

The Right of Posesión

One of the Mesta's most debated rights was the posesión. This right meant that the Mesta's members could keep using any pasture they had leased forever. This idea came from the Mesta's own rules in 1492. The goal was to stop Mesta members from competing for winter pastures. Each of the four quadrillas chose a representative to arrange grazing leases before the migration. Each member was given enough land for their sheep, and landowners were supposed to be treated fairly. This was meant to stop competition among Mesta members and prevent landowners from raising rents too much.

The 1492 rule was just for the Mesta. But in 1501, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella made it a law. This law gave Mesta members the permanent right to use a pasture field. They could pay the same rent as their first lease, or sometimes nothing if they used the land without being challenged. The idea was to give priority to the first flocks to arrive. But the Mesta managed to get the courts to interpret this rule in a way that was even better for them. They argued that since they represented all sheep owners, they had the right to arrange all pasture leases in Castile.

Landowners in southern Castile, including towns and military groups, disagreed. But the courts supported the Mesta, and more laws confirmed this in 1505. Some people believe this right of posesión stopped farming from growing and hurt Spain's development for centuries. Others think it was a way to control rents and make sure shepherds could get pastures at stable prices.

Later kings sometimes gave special permission to ignore the Mesta's rights, including posesión, in exchange for money. But in 1633, after wool sales dropped, the posesión rules were renewed. Land that had been turned into farms was ordered to be returned to pasture. This rule might not have been fully followed due to weak kings and local resistance. However, records show that more sheep owners in the 1600s included posesión rights in their wills, seeing them as valuable property.

The first two Bourbon kings of Spain renewed the Mesta's rights in 1726 and extended the posesión law to Aragon. This was more successful than the 1633 renewal. But King Charles III and his ministers thought posesión was old-fashioned and stopped farming from growing. This led to the posesión right being limited in 1761 and completely ended in 1786.

Conflicts with Transhumance

Growing crops and raising sheep often caused problems. Moving flocks from Old Castile to Andalucía led to conflicts between shepherds and farmers. It also caused problems with local sheep owners in winter pasture areas. In the 1200s and 1300s, new plows led to more grain production in Old Castile. This created more pasture land. Also, many Muslim people left New Castile, leaving more dry farming areas empty. These changes helped animal raising, and at first, there was probably enough land for both farming and grazing.

Laws confirming the Mesta's rights were issued many times in the 1300s. But these laws often had to be repeated, especially under strong kings. This showed how much people resisted the Mesta's rights. There were many arguments over illegal tolls and building on the cañadas. Farmers also plowed pastures that were only used for a few months a year. In theory, the Mesta had the right to use all land except farms, vineyards, orchards, and hay meadows. But by the end of the 1400s, these old rights were often ignored.

Special judges called Entregadors were supposed to keep the cañadas open and protect shepherds. At first, there was one for each of the four main cañada systems. Their job was to protect the Mesta's interests and settle arguments. But in 1568, the Entregadors became Mesta officers and lost their royal status.

Migrating flocks needed places to rest, eat, and drink. They were often charged too much for these stops and for winter pastures. Shepherds had little choice but to pay. Military groups also opposed northern shepherds using winter grazing in their lands. The strong kings of the late 1400s and 1500s supported wool exports. They were better able to protect Mesta members. The posesión right in the 1500s tried to control these charges and guarantee shepherds access to pastures at fixed prices.

Under later kings, there was more resistance to migrating flocks. This led to fewer small owners taking part in transhumance. The Mesta became dominated by very large flock owners. They had the money to pay for grazing and the political power to enforce their rights. Towns tried to stop or redirect flocks, or charge them as much as possible. Even though the Mesta had clear legal rights, these rights were often broken. Cañadas routes were moved, or their width was reduced. Illegal fees were charged. Even if the Mesta won in court, those who broke the rules usually faced no punishment. Both summer and winter pastures were supposed to remain unplowed, as confirmed by a royal order in 1748. In the 1700s, these uncultivated lands were under great pressure as the number of migrating sheep doubled.

During the 1600s, the power of the Entregadors slowly disappeared. The government gave towns permission to ignore the Entregadors' power if they paid for it. By the end of that century, the Entregadors were almost powerless. Local officials took control of their towns' grazing lands. They often fenced them off, claiming they were useless as pasture. By this time, the Mesta had suffered from the general economic problems of the 1600s. Its weakened Entregadors could no longer fight these local interests.

Mesta's Changes (1500s to 1700s)

Some historians believe the Mesta had its best time during the rule of Ferdinand and Isabella. They strongly promoted wool exports and reformed taxes. This made the Mesta members better off than under later kings. But Emperor Charles V greatly increased taxes on wool and forced the Mesta to give him loans. Some argue that the wool trade started to decline from the 1560s.

However, the Mesta's success went up and down, rather than just declining. Its non-migrating flocks became more important after the mid-1600s. The Mesta did face a crisis in the early to mid-1600s due to wars and economic problems in Europe. This disrupted the wool trade and made transhumance unprofitable. But the Mesta recovered.

The Mesta started because the dry climate of central Spain and the small population in newly conquered areas made sheep migration the best way to use the land. Its continued success in the 1400s and 1500s depended on the Merino sheep. Their fine wool helped the textile industries in Italy and other countries grow.

Second, the Mesta was an important source of money for the king from the 1200s. King Alfonso X wanted to tax the migrating flocks and their wool. His 1273 document set aside certain taxes for the king and limited what others could charge. The king received much of his income from wool exports collected by the Mesta. These royal sheep taxes became very important under later kings.

As long as migrating sheep produced Merino wool and the tax on wool exports was a major source of royal income, the Mesta could continue. Wars in Spain, like the War of the Spanish Succession and the Peninsular War, disrupted the migrations and destroyed many flocks. Other European wars also hindered wool exports. Although the number of sheep controlled by the Mesta recovered after each conflict, the recovery after the Peninsular War was only partial.

1700s Recovery

After a period of weakness in the late 1600s, the Mesta recovered under the first two Bourbon kings. This happened especially after the War of the Spanish Succession ended. The government enforced the Mesta's rights more strictly. The number of migrating sheep doubled between 1708 and 1780, reaching a record high around 1780. A royal order in 1748 helped by confirming that summer and winter pastures must remain unplowed.

In the 1700s, as laws controlling pasture prices were better enforced, wool exports increased. This was also helped by a decrease in Spain's population, which reduced grain farming. High wool prices and the ban on plowing pastures prevented farming from growing. But pressure from reformers later led to farming reforms. However, there is no proof that the Mesta's system failed before the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Decline of the Mesta

In the late 1700s, people who followed the Enlightenment in Spain attacked the Mesta. They had the support of King Charles III. They believed that the benefits of fine wool exports were outweighed by the damage to farming. They thought that even dry lands could be profitable for farming. They did not fully appreciate how much migrating sheep helped fertilize the land.

Farmers wanted to grow wheat on former pastures in Andalucía, even though it meant less royal income from wool taxes. King Charles III's early reforms did not immediately hurt the Mesta's wealth. Its income was highest between 1763 and 1785. But rising grain prices and falling wool prices suggested this wealth was fragile.

King Charles III was not interested in supporting the Mesta. He allowed towns and landowners to abuse its right of free passage. His actions in the late 1700s made regular sheep migrations harder. This pushed the Mesta into a final decline. Reforms in 1761 allowed towns to use their common lands as they wished. In 1783, local non-migrating flocks were given preference for pastures in Extremadura. These measures began to hurt the Mesta. A very cold winter in 1779-80 killed many sheep. Also, less demand for fine wool hurt the Mesta. Wool prices dropped a lot between 1782 and 1799. The French invasion in 1808 completely stopped the traditional sheep migrations and wool production.

Even though Merino sheep had been exported from Spain in the 1700s, Spain lost its near-monopoly on producing the finest wools in the early 1800s. The disruption from the Peninsular War led to a decline in the quantity and quality of Spanish wool. This allowed foreign producers of Merino wool to succeed.

After the Peninsular War, King Ferdinand VII again supported the Mesta's rights in 1816 and 1827. But the Mesta was actually weak, and there was strong opposition from farmers and towns. Royal support could not stop the growth of Merino wool production in South America, Australia, and South Africa. It also could not stop competition from other wools. After 1808, most Spanish wool exports were of lower quality. The number of migrating sheep fell from 2.75 million in 1818 to 1.11 million in 1832.

During the later stages of the Peninsular War, a liberal government attacked the Mesta's rights. Another liberal government later replaced the Mesta with a short-lived state body. Although the Mesta was brought back in 1823, it was weakened and linked to old-fashioned absolute rule.

The Mesta had no place in the new political system started by the liberal government in 1833. In 1835 and 1836, the Mesta lost all its private legal powers. These were given to a new "General Association of Herdsmen." It also lost its tax privileges. Finally, on November 5, 1836, the Mesta was completely dissolved.

|

See also

In Spanish: Concejo de la Mesta para niños

In Spanish: Concejo de la Mesta para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |