Michael Somare facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Right Honourable Chief Sir

Michael Somare

|

|

|---|---|

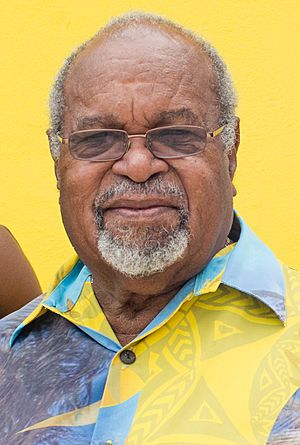

Somare in 2014

|

|

| 1st Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea | |

| In office 17 January 2011 – 4 April 2011 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General | Michael Ogio |

| Preceded by | Sam Abal (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Julius Chan (acting) |

| In office 5 August 2002 – 13 December 2010 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General |

|

| Preceded by | Mekere Morauta |

| Succeeded by | Sam Abal (acting) |

| In office 2 August 1982 – 21 November 1985 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General |

|

| Preceded by | Julius Chan |

| Succeeded by | Paias Wingti |

| In office 16 September 1975 – 11 March 1980 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chief Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Julius Chan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 April 1936 Rabaul, Territory of New Guinea, Australia |

| Died | 25 February 2021 (aged 84) Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea |

| Political party | National Alliance Party |

| Spouse |

Veronica Somare

(m. 1965) |

Sir Michael Thomas Somare (9 April 1936 – 26 February 2021) was a very important politician from Papua New Guinea. Many people called him the "father of the nation" (papa blo kantri in Tok Pisin). He was the first Prime Minister after Papua New Guinea became independent.

Sir Michael was the longest-serving prime minister. He held the job for 17 years over three different times: from 1975 to 1980, from 1982 to 1985, and from 2002 to 2011. His political career was very long, lasting from 1968 until he retired in 2017. Besides being Prime Minister, he also served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs, leader of the opposition, and governor of East Sepik Province.

He was a founding member of the Pangu Party. This party helped lead Papua New Guinea to independence in 1975. Later, he joined and led the National Alliance Party.

In 2011, while Somare was in the hospital, some members of parliament said the Prime Minister's job was empty. Peter O'Neill became the new prime minister. This caused a big disagreement. The Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea later said Somare should be Prime Minister again. This led to a time of political trouble called the 2011–12 Papua New Guinean constitutional crisis. After a new election in 2012, O'Neill won. Somare then supported O'Neill, which ended the crisis.

Contents

Early life and education

Michael Somare was born in Rabaul in 1936. His father, Ludwig Somare Sana, was a policeman who taught himself to read and write. Michael grew up in his family's village of Karau in the Murik Lakes area of East Sepik Province.

During World War II, Michael went to a Japanese-run primary school in Karau. There, he learned to read, write, and count in Japanese. He later attended other schools, including Sogeri High School. He finished school in 1957, which allowed him to become a teacher. He taught at several schools and continued his own training.

Sepik culture and leadership

Somare often wore a lap-lap, which is a traditional wrap-around skirt, instead of trousers. This showed his connection to his culture. Even though he was born in Rabaul, he felt a strong connection to his Sepik identity. He believed his childhood in Sepik villages shaped who he became.

In Sepik culture, leaders are chosen based on agreement among elders and their good reputation. This is different from leadership based on family lines. This idea of leadership, where people work together and leaders step aside when they lose support, is called the "Melanesian way" in Papua New Guinea. This way of thinking influenced Somare's political style. He believed in building agreement and avoiding conflict.

Papua New Guinea uses a Westminster style democracy. This means leaders need the support of the parliament to stay in power. Somare strongly believed in this system.

Starting in politics

Michael Somare was one of the first Papua New Guineans to get a good education and learn English. This helped him become a translator for the Legislative Council, which was a government group. This job helped him understand how politics worked.

He also worked as a radio announcer in Wewak, East Sepik. This made him well-known in the area that would later elect him as their representative. He was part of a small group of educated people who wanted Papua New Guinea to be independent. This group was called the "bully beef club."

In 1967, Somare helped start the Pangu Party. In 1968, he was elected to the National Assembly. He became the leader of the opposition. He worked to end colonial rule and helped create the country's constitution. He pushed for Papua New Guinea to govern itself, which happened in 1973. Full independence came two years later.

Somare was skilled at bringing different groups together. Papua New Guinea had many different regions and groups, some of whom wanted to be separate. He managed to unite these groups, including the People's Progress Party led by Julius Chan, to work towards independence. His ability to build agreement was key to the country's smooth path to becoming independent.

Making policies for the country

Michael Somare was known for being a leader who brought people together. He helped a country with many different groups become independent and keep its democracy.

When it came to making specific policies, Somare often reacted to events rather than setting out big plans beforehand. For example, even though Papua New Guinea was advised to focus on farming, it became more focused on getting natural resources like oil and gas. The biggest natural gas project, LNG/PNG, was developed when he was prime minister.

One clear thing about his governments was that they were careful with money. When he was prime minister from 2002 to 2011, his government kept spending under control. They used money from natural resources to reduce the country's debt instead of spending it all.

His government did try to create a big plan for the future called "Vision 2050." This document was more about inspiring people than giving exact steps. It talked about how Papua New Guinea had done since independence and encouraged citizens to do better.

Working with other countries

Michael Somare traveled a lot before becoming prime minister. He believed in being "friends with everybody and enemies of none" when dealing with other countries.

Relations with Japan

He felt a special connection to Japan. He spoke positively about the Japanese presence in his home area during World War II. He visited Japan often and received high honors from them. This friendship did not stop him from starting diplomatic relations with China soon after independence.

Relations with Indonesia

Indonesia was another important country for Papua New Guinea. Somare's government tried to stay neutral about the conflict between the Indonesian government and people in West Papua who wanted independence. Papua New Guinea never questioned Indonesia's control over West Papua.

However, after a big uprising in 1984, many refugees came to Papua New Guinea. This led Papua New Guinea to speak up about human rights in the region at the United Nations. The main goal was always to help the refugees return home. Somare believed that West Papua's situation was an internal problem for Indonesia. He suggested that West Papuans could be represented in regional groups like the Melanesian Spearhead Group as a community, not as an independent state.

Relations with Australia

Australia was also a very important country for Papua New Guinea. The relationship often depended on the leaders in power. Somare sometimes showed his strong national pride in dealings with Australia.

For example, when Papua New Guinea became independent in 1975, Somare felt that Australia's gift of a prime minister's house was not grand enough. Australia then provided a much larger house.

In 2005, Somare had to take off his shoes at Brisbane Airport during a security check. He was very upset by this, and it caused a diplomatic disagreement between the two countries. Somare felt it was disrespectful to him as a leader.

After returning to power in 2002, Somare said he would manage relations with Australia differently. He opposed Australia's "Pacific solution" program, which involved sending asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea. In 2005, he also complained that Australia was trying to control Papua New Guinea again.

Family life

Michael Somare married Veronica, Lady Somare in 1965. They had five children: Bertha, Sana, Arthur, Michael Jnr, and Dulciana. Lady Veronica also received a special cultural title from her family, showing her importance.

Michael Somare passed away in Port Moresby on 25 February 2021, at the age of 84. He died from pancreatic cancer.

Awards and recognition

Michael Somare received many honors during his life. He was given honorary doctorates from universities. In 1977, he became a member of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, which allowed him to use the title "The Right Honourable."

In 1990, Queen Elizabeth II made him a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG). In 2005, he was one of the first people to be named a Grand Companion of the Order of Logohu (GCL), which is Papua New Guinea's own honors system.

Awards and Orders

| Country | Award or Order | Class or Position | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Privy Council of the United Kingdom | Privy Councilor | 1977 |

| United Kingdom | Order of the Companions of Honour | Companion of Honour | 1978 |

| United Kingdom | Order of St Michael and St George | Knight Grand Cross | 1991 |

| Papua New Guinea | Order of Logohu | Grand Companion | 2005 |

| Fiji | Order of Fiji | Companion | year unknown (2005?) |

| United Kingdom (Royal Order) | Venerable Order of Saint John | Knight of Justice | year unknown |

| Vatican City | Order of St. Gregory the Great | Knight | 1992 |

| Japan | Order of the Rising Sun | Grand Cordon | 2015 |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Michael Somare para niños

In Spanish: Michael Somare para niños