Mind–body dualism facts for kids

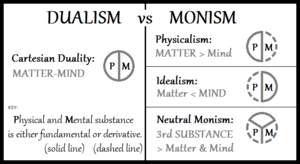

In philosophy, mind–body dualism is the idea that your mind and your body are two very different things. It suggests that your thoughts, feelings, and consciousness (your mind) are not physical, and they might even be able to exist separately from your physical body. This idea is different from other views that say the mind is just a part of the brain, or that everything is physical.

Ancient Greek thinkers like Plato and Aristotle also thought about the mind and body. Plato believed in different kinds of souls. He thought the soul was not tied to the physical body and could move to a new body after death. Aristotle agreed there were different souls for plants, animals, and humans. He believed the parts of the soul related to the body would die with the organism, but the part that allowed for reason in humans was immortal.

The idea of dualism is most famous because of René Descartes in the 1600s. He said the mind is a non-physical thing that can think and be aware of itself. He saw the brain as the place where intelligence happens, but the mind itself was separate. Descartes was one of the first Western philosophers to clearly explain the mind-body problem as we understand it today.

Contents

Types of Dualism

There are a few main ways to think about dualism:

- Substance dualism says that the mind and body are completely different kinds of things, or "substances."

- Property dualism suggests that while there might be only one kind of "stuff" (physical matter), this matter can have two different kinds of "properties"—physical properties and mental properties.

- Predicate dualism argues that we use different kinds of words (predicates) to describe mental things than we do for physical things, and you can't easily change one into the other.

Substance Dualism (Cartesian Dualism)

Substance dualism, also known as Cartesian dualism (named after René Descartes), is the idea that there are two basic kinds of things: mental things and physical things. This philosophy says that your mind can exist without your body, and your body cannot think on its own. This idea was very important in history because it led to many discussions about the famous mind–body problem.

During the 1600s, new scientific discoveries made people believe that science was the best way to gain knowledge. Bodies were seen as biological machines that could be studied in parts, using fields like anatomy and physics. Even with these new ideas, the mind-body dualism remained a popular way to think about humans for a long time.

Substance dualism fits well with many religions that believe in immortal souls living in a separate, non-physical world. Some modern philosophers have suggested less extreme forms of substance dualism that fit better with ideas like evolutionary biology.

Property Dualism

Property dualism says that the difference between mind and matter is in their properties. It suggests that when matter is arranged in a certain way (like in a human body), mental properties like consciousness appear. These mental properties might not be explainable just by looking at neurobiology or physics. It's like saying that a cake has the property of being delicious, which isn't just about the flour and sugar.

One type of property dualism is called non-reductive physicalism. This view says that all mental states are caused by physical states, but you can't completely reduce mental states to just physical ones. For example, John Searle's idea of biological naturalism says that mental states are caused by the brain, but they are still real mental experiences that can't be fully explained by just looking at neurons.

Epiphenomenalism

Epiphenomenalism is a specific type of property dualism. It says that mental states, like feelings or thoughts, are caused by physical events in the brain, but these mental states don't cause anything physical themselves. They are like a shadow – they are there, but they don't make anything happen. For example, if you decide to pick up a rock, the firing of neurons in your brain causes both your decision and your arm to move. But your decision itself doesn't cause your arm to move; only the neurons do.

This idea was discussed by thinkers like T.H. Huxley in the 1800s.

Predicate Dualism

Predicate dualism is the idea that we use different kinds of words to talk about mental events than we do for physical events. For example, words like "believe," "desire," or "think" are used for mental things, and you can't easily replace them with words used for physical things.

This view is different from "predicate monism," which says that eventually, we might get rid of mental words because the things they refer to don't really exist. Predicate dualists believe that our everyday way of talking about beliefs and desires is a necessary part of understanding human minds and behavior.

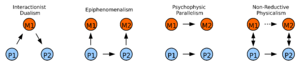

Dualist Views of Mental Causation

This section looks at how mental and physical states might affect each other.

Interactionism

Interactionism is the idea that mental states (like your beliefs and desires) can cause physical states, and physical states can cause mental states. This idea feels very natural to most people. For example, if a child touches a hot stove (a physical event), they feel pain (a mental event). Then they yell (a physical event), which makes their parents feel worried (a mental event).

Non-reductive Physicalism

Non-reductive physicalism says there's only one kind of substance (physical stuff), but it has two kinds of properties: mental and physical. Mental properties can't be fully explained by physical ones. However, all mental states are still caused by physical states. This means that mental properties are linked to physical properties.

Epiphenomenalism

As mentioned before, Epiphenomenalism states that mental events are caused by physical events but don't have any physical effects themselves. They are like side effects. So, your decision to pick up a rock is caused by your brain, and your arm moving is also caused by your brain, but your decision itself doesn't make your arm move.

Parallelism

Psychophysical parallelism is a very unique idea, mainly supported by Gottfried Leibniz. He thought that God created the universe in such a way that mental and physical events happen side-by-side, perfectly matched, but they don't actually cause each other. It just seems like they do. So, mental causes only have mental effects, and physical causes only have physical effects.

Occasionalism

Occasionalism is a philosophy that says created things cannot cause events. Instead, God directly causes all events. So, when you decide to move your hand, it's not your mind causing your hand to move; it's God causing your hand to move at the same time as your decision. The decision is just the "occasion" for God to act.

Kantianism

Immanuel Kant believed there's a difference between actions done because of desires and actions done because of reason and freedom. He thought that not all physical actions are caused by just matter or just freedom. Some actions are purely animal-like, while others come from the mind's free choice acting on the body.

History of Dualism

Ancient Greek Philosophy

Early Greek thinkers like Hermotimus of Clazomenae and Anaxagoras suggested that the mind was important for causing change, while physical things were static.

Plato, in his dialogue Phaedo, developed his famous Theory of Forms. He believed that perfect, unchanging Forms (like the idea of "beauty" or "justice") exist separately from the physical world. The things we see in the world are just imperfect copies or "shadows" of these Forms. Plato thought these Forms were non-physical and didn't exist in time or space.

Aristotle disagreed with some of Plato's ideas about Forms existing separately. Aristotle believed that form and matter always exist together. He thought the mind could take on the form of whatever it was thinking about or experiencing, and it had the unique ability to be a "blank slate."

From Neoplatonism to Scholasticism

Later philosophical schools like Neoplatonism believed that both the physical and spiritual worlds came from a single source called "the One." This idea influenced Christianity.

In the Christian tradition, especially with Saint Thomas Aquinas, the soul was seen as the "form" of a human being. Aquinas believed that humans are a mix of body and soul. He argued that the intellectual soul (the part that reasons) is not physical and can survive after the body dies. However, he also believed that a separated soul is not a complete human person.

The Catholic belief in the resurrection of the body shows this idea of body and soul forming a whole. It states that at the end of time, souls will be reunited with their bodies.

Descartes and His Followers

In his book Meditations on First Philosophy, René Descartes started by doubting everything he thought he knew. He realized he could doubt if he had a body, but he couldn't doubt that he had a mind. This made him think that the mind and body were different. Descartes described the mind as a "thinking thing" (res cogitans) and the body as an "extended thing" (res extensa). He believed animals only had bodies, not souls.

The main idea of Cartesian dualism is that the non-physical mind and the physical body are separate but can still affect each other. Mental events can cause physical events, and physical events can cause mental events. This led to a big problem: How can something non-physical affect something physical, and vice versa? This is called the "problem of interactionism."

Descartes struggled to answer this. He suggested that the mind and body interacted through the pineal gland in the brain. But this didn't fully explain how an immaterial mind could interact with a physical gland. Because Descartes' theory was hard to defend, some of his followers, like Arnold Geulincx and Nicolas Malebranche, suggested that God directly caused all mind-body interactions. This idea is called occasionalism.

Recent Ideas

New ideas about dualism have emerged. David Chalmers proposes Naturalistic dualism, arguing that there's a gap in explaining consciousness that science can't bridge yet. He thinks consciousness might be a basic property of the universe, needing new laws to understand it.

Frank Jackson also discussed dualism, especially epiphenomenalism, which says mental states don't affect physical ones. He used a famous thought experiment called Mary's room. Imagine Mary, a scientist who knows everything about colors but has only lived in a black and white room. Jackson argued that when she finally sees color, she learns something new – what it's like to experience color. This suggests there's a non-physical aspect to experience. However, Jackson later changed his mind and became a physicalist.

Arguments for Dualism

The Subjective Argument

This argument says that mental experiences have a special "subjective" quality that physical things don't. For example, what does it feel like to burn your finger, or what does the color blue look like? Philosophers call these subjective aspects qualia. The argument is that qualia cannot be reduced to anything purely physical.

Thomas Nagel explored this in his paper "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" He argued that even if we knew everything about a bat's brain and sonar system, we still wouldn't know what it's like to be a bat.

The Zombie Argument

The zombie argument is another thought experiment by David Chalmers. It asks you to imagine a "philosophical zombie" – a being that looks and acts exactly like a human, but has no consciousness or inner experience. Chalmers argues that if you can imagine such a zombie, it means consciousness is something separate from just physical processes. If a zombie could exist, it would show that consciousness is a natural phenomenon that our current science doesn't fully explain.

However, some philosophers like Daniel Dennett argue that the idea of a philosophical zombie doesn't make sense. They say that if something perfectly mimics human behavior and expressions of feelings, it would likely also experience those feelings.

Argument from Personal Identity

This argument looks at how we understand our own identity. For a physical object, like a printer, you can imagine it being made of slightly different parts, and it's still the same printer. But for a person, it's harder. If you imagine a copy of yourself, even if it's 70% physically the same, does it feel 70% like you? This argument suggests that our personal identity, our "self," is not just about our physical parts.

Richard Swinburne used a thought experiment: what if your brain's two halves were put into two different people? Which one would be "you"? He argued that even if we knew every atom in your brain, we still wouldn't know what happened to "you" as an identity. This suggests that a part of our mind or soul is non-physical.

Argument from Reason

Philosophers like C.S. Lewis have argued that if all our thoughts are just the result of physical causes in our brain, then we can't trust that our thoughts are actually true or logical. If our beliefs are just atoms moving, why should we think they are correct? This argument suggests that for us to truly reason and gain knowledge, our minds must be more than just physical processes.

Lewis quoted J. B. S. Haldane: "If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true...and hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms."

Arguments Against Dualism

Arguments from Causal Interaction

One of the biggest arguments against dualism is the problem of how the mind and body interact. If the mind is non-physical, how can it cause things to happen in the physical brain and body? And how can physical events in the brain cause mental experiences?

Critics ask:

- Where does the interaction happen? If pain is not physical, where does it "take place" when you burn your finger?

- How does the interaction happen? If your decision to move your arm is a mental event with no physical force, how can it make neurons fire? This seems to go against the laws of physics.

Replies to Interaction Arguments

Some replies suggest that the mind might influence how energy is distributed in the brain, without changing the total amount of energy. Others argue that the human body might not be a "closed system" in terms of energy, allowing for non-physical influence. Some even suggest that unknown scientific processes, like dark energy or dark matter, might be involved, though this would make it a physical process, not a dualistic one.

Another idea is that if quantum mechanics is true, then very small events might be unpredictable, and perhaps this unpredictability allows for the mind to influence the brain.

Argument from Brain Damage

This argument, made by philosophers like Paul Churchland, points out that when the brain is damaged (from an accident or disease), a person's mental abilities and personality are almost always affected. If the mind were completely separate from the brain, how could this happen? We can often even predict what kind of mental changes will occur based on which part of the brain is damaged. This suggests a very strong connection, or even identity, between the brain and the mind.

For example, the famous case of Phineas Gage, who had a metal rod go through his brain, showed big changes in his personality. This physical damage clearly affected his mind. Modern neuroscience also shows that manipulating specific brain areas can reliably change mental states, suggesting a direct causal link.

Argument from Biological Development

This argument says that humans start as purely physical beings (like a fertilized egg) and nothing non-physical is added during development. Therefore, we must be entirely physical beings. The idea of a non-physical mind seems unnecessary if everything can be explained by physical development.

Argument from Neuroscience

Modern neuroscience provides strong evidence that mental processes have a physical basis in the brain. For example, scientists can sometimes detect a person's decisions up to 10 seconds before they are aware of them, by looking at brain activity. They can also detect subjective experiences and thoughts by scanning the brain. This suggests that our thoughts and feelings are deeply connected to, or are, our brain activity.

Argument from Simplicity

This is often called Occam's razor. It's a rule in science and philosophy that says we should not assume more things exist than are necessary to explain something. If we can explain the mind and its properties using only physical things (the brain), then why should we believe in a separate, non-physical mind? It's simpler to assume one thing (physical brain) than two (physical brain and non-physical mind).

Some argue that Occam's razor might not apply to abstract concepts like the mind, but generally, it encourages looking for the simplest explanation first.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dualismo mente-cuerpo para niños

In Spanish: Dualismo mente-cuerpo para niños