J. B. S. Haldane facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J.B.S. Haldane

|

|

|---|---|

Haldane in 1914

|

|

| Born |

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane

5 November 1892 Oxford, England

|

| Died | 1 December 1964 (aged 72) Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Naomi Mitchison (sister) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors | Frederick Gowland Hopkins |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1914–1920 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Black Watch |

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (5 November 1892 – 1 December 1964) was a brilliant British-Indian scientist. People often called him "Jack" or "JBS." He made big contributions in many areas like physiology (how living things work), genetics (how traits are passed down), and evolutionary biology (how life changes over time).

Haldane was one of the key people who helped create neo-Darwinism. This idea combines Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection with Gregor Mendel's ideas about genetics. He used statistics in biology in new ways to understand these topics better.

During World War I, Haldane served as a captain in the British Army. Even though he didn't have a formal degree in biology, he taught the subject at important universities like University of Cambridge and University College London. In 1961, he gave up his British citizenship and became an Indian citizen. He then worked at the Indian Statistical Institute for the rest of his life.

Haldane introduced the "primordial soup theory" in 1929. This theory explains how life might have started from simple chemicals on early Earth. He also helped create the first gene maps for human conditions like haemophilia and color blindness. He was the first to suggest the idea of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), where eggs are fertilized outside the body. He also came up with ideas like the hydrogen economy and the concept of cloning.

In 1957, Haldane described "Haldane's dilemma." This idea talks about how fast beneficial changes can happen in evolution. He was known for his unique personality and for using himself in his experiments. He even donated his body for medical studies after he died. Many famous scientists called him one of the smartest and most important biologists of his time.

Contents

A Scientist's Life

Early Years and Learning

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane was born in Oxford, England, in 1892. His father, John Scott Haldane, was a well-known scientist who studied how bodies work. His mother, Louisa Kathleen Trotter, came from a Scottish family. John had one sister, Naomi Mitchison, who became a famous writer.

From a young age, Haldane showed he was very smart. He learned to read by age three. When he was four, after hurting his forehead, he asked the doctor about the type of blood he saw. This showed his early interest in science.

He often worked with his father in their home laboratory. This is where he first tried "self-experimentation." This meant he would test things on himself. For example, he and his father studied the effects of poison gases by breathing small amounts of them.

When he was eight, his father took him to a lecture about Mendelian genetics. This was a new idea about how traits are passed from parents to children. Even though it was hard to understand, it made a lasting impression on him. Genetics later became the field where he made his most important discoveries.

Haldane went to Eton College for high school. He studied mathematics and ancient Greek and Roman literature at New College, Oxford. He graduated with top honors in 1914. He planned to study physiology, but World War I changed his plans.

Serving in the War

In 1914, Haldane joined the British Army to help with the war effort. He became an officer in the Black Watch regiment. He was a trench mortar officer, meaning he led a team that threw bombs into enemy trenches. He even wrote a scientific paper from the front lines, which was very unusual!

He was wounded twice during the war. Once by artillery fire in France and again by a bomb in Iraq. After his injuries, he served as an instructor in Scotland and then in India. He returned to England in 1919 as a captain. His commander described him as "the bravest and dirtiest officer in my Army" because of his fierce fighting.

Academic Journey

After the war, Haldane became a Fellow at New College, Oxford, in 1919. He taught and researched physiology and genetics. He published six papers in his first year there.

In 1923, he moved to the University of Cambridge to teach biochemistry. For nine years, he focused on enzymes (proteins that speed up chemical reactions) and the mathematical side of genetics. While visiting the University of California in 1932, he was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a very high honor for scientists.

From 1927 to 1937, Haldane also worked part-time at the John Innes Horticultural Institution. He was in charge of genetics research. In 1933, he became a full Professor of Genetics at University College London. He spent most of his career there. During World War II, he moved his team to a safer location to avoid bombings. He also became the editor of the Journal of Genetics in 1933 and stayed in that role until his death.

Life in India

In 1956, Haldane left University College London and moved to India. He joined the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata. He gave several reasons for his move. He said he disagreed with the British government's actions during the Suez Crisis. He also believed the warm climate would be good for his health. He felt India shared his ideas about a socialist society, where everyone is equal.

Haldane was interested in doing scientific research that didn't cost a lot of money. He wrote that he could find things like gardens and pigeons more easily in India than in England. He studied local plants and animals, like the yellow-wattled lapwing bird. He also noticed that Indian universities often made biology students drop mathematics, which he thought was a mistake.

In 1961, Haldane officially became an Indian citizen. He was interested in Hinduism and became a vegetarian. He believed India was "the closest approximation to the Free World."

Personal Life

Haldane was married twice. His first wife was Charlotte Franken, a journalist. They married in 1926 and divorced in 1945. Later that year, he married Helen Spurway, who had been his student.

Haldane was known for his intelligence and his unique habits. He once said he could read 11 languages and give speeches in three. He didn't have any children of his own. However, he and his father greatly influenced his sister Naomi's children, many of whom became biology professors.

Following his father's example, Haldane often used himself in his experiments. He would put himself in dangerous situations to collect data. For instance, he drank dilute acid to study its effects on his blood. In one experiment, he suffered crushed bones in his spine. In other experiments, his eardrums were damaged, but he joked that he could then blow tobacco smoke out of his ear!

Haldane sometimes annoyed his colleagues with his behavior. But he was always dedicated to science.

Later Life and Passing

In 1963, Haldane visited the United States for scientific conferences. While there, he started feeling stomach pains. He went to London for a diagnosis and found out he had colorectal cancer. He had surgery in February 1964.

While in the hospital, he wrote a funny poem about his illness. It showed his humorous and rebellious spirit, even when facing death. The poem was published in a magazine and made his friends laugh.

He decided that his body should be used for medical research and teaching after he died. This showed his wish to keep helping science even after his life ended. His surgery was thought to be successful, but his symptoms returned in India. Doctors confirmed his condition was terminal.

J.B.S. Haldane died on December 1, 1964, in Bhubaneswar, India. On that day, the BBC broadcast his self-written obituary.

Amazing Scientific Discoveries

Haldane followed in his father's footsteps, with his first published work being about how blood carries gases. He also studied how kidneys work.

Genetic Linkage

In 1904, a scientist named Arthur Dukinfield Darbishire published a paper about genetics in mice. Haldane noticed that Darbishire had missed something important: the idea of genetic linkage. This means that certain genetic traits tend to be inherited together because they are located close to each other on the same chromosome.

With his sister Naomi and a friend, Haldane started his own experiments in 1908 using guinea pigs and mice. Their paper, published in 1915, was the first to show genetic linkage in mammals. Haldane wrote this paper while serving in World War I. He was the "only officer to complete a scientific paper from a forward position of the Black Watch." He also showed linkage in chickens in 1921 and in humans in 1937.

Enzyme Kinetics

In 1925, Haldane and G.E. Briggs developed a new way to understand how enzymes work. Enzymes are like tiny machines in our bodies that speed up chemical reactions. Their work helped explain the Michaelis–Menten kinetics equation, which describes how fast enzymes work depending on how much of the substance they are acting on is present. Their explanation is still used today.

Haldane's Principle

In his essay On Being the Right Size, Haldane explained a key idea called Haldane's principle. This principle states that an animal's size often determines what body parts it needs. For example, very small insects don't need blood to carry oxygen. Their cells can just absorb oxygen directly from the air. But larger animals need complex systems, like lungs and blood, to get oxygen to all their cells.

Haldane's Sieve

In 1927, Haldane pointed out that new dominant mutations (traits that show up even if only one copy of the gene is present) are more likely to become common than recessive mutations (traits that only show up if two copies of the gene are present). This is because natural selection acts more strongly on dominant traits. This idea is now called Haldane's sieve. It helps explain how new adaptations spread in large populations.

How Life Began

Haldane introduced the modern idea of abiogenesis (how life started from non-living things) in 1929. He wrote that the early ocean was like a "vast chemical laboratory" or a "hot dilute soup." This soup contained simple chemicals. With energy from the sun, these chemicals could have formed more complex organic compounds.

He suggested that the first living things might have been like viruses. These "half-living things" could have been around for millions of years before forming the first cells. In a cell, an "oily film" would have enclosed self-replicating molecules, like DNA.

A Russian scientist named Alexander Oparin had a similar idea in 1924. The "primordial soup theory" (also called the Oparin–Haldane hypothesis) became very important. In 1953, the Miller–Urey experiment showed that simple organic molecules could indeed form from basic chemicals, supporting this theory. Haldane always gave Oparin credit for having the idea first.

Malaria and Sickle-Cell Anemia

Haldane was the first to see a connection between genetic problems and infections in humans. He noticed that certain blood disorders, like thalassemias and sickle cell trait, were common in tropical areas where malaria was widespread.

He suggested that having one copy of the gene for sickle cell disease (being a heterozygous carrier) might protect people from malaria. This idea, called "Haldane's malaria hypothesis," was a big step in understanding how diseases and genetics are linked. Later, in 1954, Anthony C. Allison confirmed this hypothesis for sickle-cell anemia.

Population Genetics

Haldane was one of three main scientists, along with Ronald Fisher and Sewall Wright, who developed the mathematical theory of population genetics. This field uses math to understand how gene frequencies change in populations over time. His work was crucial for the "modern evolutionary synthesis." This combined Mendel's genetics with Darwin's natural selection.

He wrote a series of ten papers called A Mathematical Theory of Natural and Artificial Selection between 1924 and 1934. In these papers, he explained how natural selection, mutation, and migration affect gene frequencies. He also wrote a book, The Causes of Evolution (1932), based on these ideas.

His first paper in 1924 looked at the rate of natural selection in peppered moth evolution. He predicted how quickly the dark-colored moths would become more common in polluted areas. His predictions were later proven correct by experiments.

Haldane also developed methods to estimate human mutation rates and create human gene maps. He was the first to suggest that there is a "cost of natural selection," meaning that evolution can be slow because it takes time for beneficial genes to spread.

Views and Legacy

Political Views

Haldane became a socialist during World War I. He supported the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. In 1937, he openly supported the Communist Party of Great Britain. He wrote many articles for the Daily Worker, a communist newspaper.

He believed that Marxism (a political and economic theory) was true. He joined the Communist Party in 1942. He often criticized how scientific research depended on money from wealthy people. He left the party in 1950. Even after leaving, he continued to admire Joseph Stalin, a leader of the Soviet Union.

Human Cloning

Haldane was the first to think about the genetic basis of human cloning. He also thought about how to artificially create "better" individuals. He introduced the terms "clone" and "cloning" in a speech in 1963. He used these terms to describe the idea of making exact genetic copies of organisms.

Ectogenesis and In Vitro Fertilisation

In his 1924 essay Daedalus; or, Science and the Future, Haldane introduced the idea of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), which he called ectogenesis. This means growing an organism outside the body. He imagined ectogenesis as a way to create improved individuals. His ideas influenced famous books like Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

Criticism of C. S. Lewis

Haldane disagreed with the writer C. S. Lewis, who criticized science. Haldane felt Lewis unfairly presented science and looked down on humanity. Haldane even wrote a children's book called My Friend Mr Leakey (1937). He also wrote an essay called "More Anti-Lewisite" to argue against Lewis's ideas about God.

Hydrogen-Generating Windmills

In 1923, Haldane gave a talk where he predicted that Britain would run out of coal for power. He suggested building a network of windmills that would generate hydrogen for energy. This was the first time someone proposed the idea of a hydrogen-based renewable energy economy.

Awards and Honors

Haldane received many awards for his scientific work. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1932. The French Government gave him the Legion of Honour in 1937. He received the Darwin Medal in 1952 and the Darwin–Wallace Medal in 1958. He also received honorary doctorates and other prestigious awards.

Legacy

Haldane is remembered for his huge contributions to genetics, evolution, and physiology. The Haldane Lecture at the John Innes Centre and the JBS Haldane Lecture are named in his honor.

His friend Aldous Huxley even parodied him in a novel, showing how Haldane was known for being so focused on his experiments that he sometimes seemed unaware of what was happening around him.

Famous Sayings

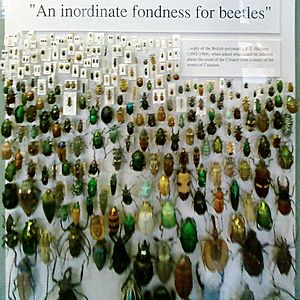

- When asked what could be learned about a Creator from nature, Haldane famously replied, "An inordinate fondness for beetles." This means he thought the Creator must really love beetles because there are so many different kinds!

- "My own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose."

- "It seems to me immensely unlikely that mind is a mere by-product of matter. For if my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true."

- "Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her but he's unwilling to be seen with her in public." (This means biologists often think about purpose in nature, but they don't always like to admit it openly.)

- "I suppose the process of acceptance will pass through the usual four stages: (i) This is worthless nonsense; (ii) This is an interesting, but perverse, point of view; (iii) This is true, but quite unimportant; (iv) I always said so." (This describes how new scientific ideas are often received.)

- When asked if he would die for his brother, Haldane supposedly replied, "two brothers or eight cousins." This was a clever way to hint at the idea of Kin selection, where animals might sacrifice themselves for relatives to pass on shared genes.

Images for kids

-

J. B. S. Haldane Avenue in Kolkata, India

-

Lysenko speaking at the Moscow Kremlin in 1935. Behind him are (left to right) Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrey Andreyevich Andreyev, and Joseph Stalin.

-

Oxford University Museum of Natural History display dedicated to Haldane and his reply when asked to comment on the mind of the Creator.

See also

In Spanish: John Burdon Sanderson Haldane para niños

In Spanish: John Burdon Sanderson Haldane para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |