Newburgh Conspiracy facts for kids

The Newburgh Conspiracy was a tense situation that happened in March 1783, right at the end of the American Revolutionary War. It involved leaders of the Continental Army who were upset about not being paid. The army's commander, George Washington, stepped in and successfully calmed his soldiers. He also helped them get the money they were owed.

Some people in the Congress might have started the problem. They sent an anonymous letter around the army camp in Newburgh, New York, on March 10, 1783. The soldiers were very unhappy because they hadn't been paid for a long time. Also, they had been promised pensions (money after they stopped working) that they hadn't received. The letter suggested they should take strong action against Congress to fix this.

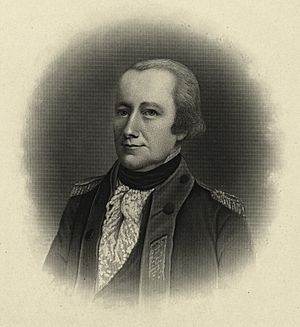

Many historians believe Major John Armstrong, Jr., an aide to General Horatio Gates, wrote the letter. However, who wrote it and why are still debated by historians. Commander-in-Chief George Washington stopped any serious talk of a rebellion. He gave an emotional speech to his officers, asking them to support Congress. Soon after, Congress agreed to a deal it had rejected before. They paid some of the back wages. They also gave soldiers five years of full pay instead of a lifetime pension.

Historians still discuss why different people acted the way they did during these events. Most historians think that politicians were behind the plot. Their goal was to make Congress keep its promises to the soldiers. Some historians think that the army seriously considered taking over the government. Others disagree with this idea. The exact reasons why congressmen talked with army officers are also debated.

Contents

Why Were Soldiers Upset?

After the British lost the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, the American Revolutionary War mostly ended in North America. Peace talks then began between British and American leaders. The American Continental Army was stationed at Newburgh, New York. They were watching British-occupied New York City.

As the war was ending and the army was about to break up, soldiers worried. They had not been paid for a long time. They feared that the Confederation Congress would not keep its promises about back pay and pensions.

In 1780, Congress had promised officers a lifetime pension. This pension would be half of their pay after they left the army. Robert Morris, who handled the country's money, stopped army pay in early 1782. He did this to save money. He said that all the unpaid money would be given to them when the war finally ended.

Throughout 1782, these money problems were often discussed in Congress and at the Newburgh army camp. Many letters and requests from individual soldiers did not change Congress's mind much.

Officers Send a Message to Congress

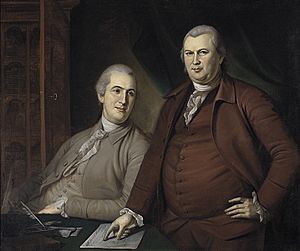

A group of officers, led by General Henry Knox, wrote a message to Congress. Many general officers signed it, so it couldn't be ignored. General Alexander McDougall and Colonels John Brooks and Matthias Ogden delivered this message to Congress in late December 1782.

The message showed how unhappy the officers were about their unpaid wages. They also worried that the half-pay pension would not be given. In the message, they offered to take a one-time payment instead of a lifetime pension. The message also included a vague warning. It said that "any further experiments on their [the army's] patience may have fatal effects." Secretary at War Benjamin Lincoln also told Congress how serious the situation was.

What Did Congress Do?

Congress was very divided about money. Rhode Island, for example, stopped any action. The country's treasury was empty. Congress did not have the power to force states to provide the money needed to pay its debts.

An attempt to change the Articles of Confederation failed. This change would have allowed Congress to collect an import tax. States strongly rejected it in November 1782. Some states had even passed laws forbidding their representatives from supporting any lifetime pension.

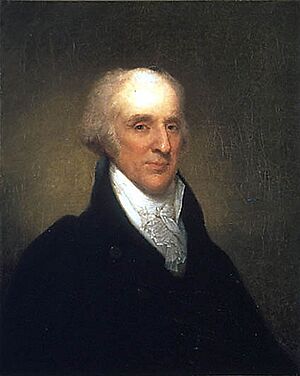

Members of the "nationalist" group in Congress supported the tax idea. These included Robert Morris, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. They believed that the army's money problems could be used. They hoped it would force Congress to get the power to raise its own money. Historian Richard Kohn says that Hamilton, Robert Morris, and Gouverneur Morris were the main leaders of this "conspiracy." Another historian, Jack N. Rakove, highlights Robert Morris's leadership.

The army's representatives first met with Robert Morris and other nationalists. The politicians convinced General McDougall that the army needed to stay cooperative. They hoped to link the army's demands with those of other people Congress owed money to. This would force opposing Congressmen to act.

On January 6, Congress created a committee to deal with the army's message. They first met with Robert Morris. He said there was no money to meet the army's demands. He also said that loans for the government would need proof of a steady income. When the committee met with McDougall on January 13, the general described the strong unhappiness at Newburgh. Colonel Brooks said that "a disappointment might throw [the army] into blind extremities."

When Congress met on January 22 to discuss the committee's report, Robert Morris surprised everyone. He offered to resign, which made the tension even higher. The leaders in Congress quickly decided to keep Morris's resignation a secret.

Plans to Increase Pressure

Debate about a funding plan focused on the pension issue. The nationalists twice urged Congress to approve a pension plan that would end after a set time, not a lifetime. Both times, it was rejected. After the second rejection on February 4, a plan to increase tensions began to form.

Four days later, Colonel Brooks was sent back to Newburgh. He was told to get the army leaders to agree with the nationalist plan. Gouverneur Morris also urged the army leaders to use their influence with state governments. This was to get approval for needed changes.

On February 12, McDougall sent a letter signed with the fake name Brutus to General Knox. It suggested that the army might have to refuse to break up until they were paid. He told Knox not to take direct action but to "not lose a moment preparing for events." Historian Richard Kohn believes these messages were not meant to cause a military takeover. Instead, they aimed to use the idea of a stubborn army refusing to disband as a political tool. This was against those who opposed the nationalists.

The nationalists also knew about many lower-ranking officers. These officers were unhappy with General Washington's leadership. They had gathered around Major General Horatio Gates, who was a long-time rival of Washington. Kohn believes these officers could be used by the nationalists to create something that looked like a takeover if needed.

On February 13, rumors arrived that a peace agreement had been reached in Paris. This made the nationalists feel even more urgent. Alexander Hamilton wrote a letter to General Washington that same day. He warned Washington about possible unrest among the soldiers. He urged Washington to "take the direction" of the army's anger.

Washington replied that he understood his officers' and men's problems. He also sympathized with Congress. But he said he would not use the army to threaten the government. Washington believed such an action would go against the ideas of republicanism they had fought for. It was unclear to the Congressional nationalists if Knox, who often supported army protests, would join any staged action. In letters written on February 21, Knox clearly said he would not. He hoped the army's strength would only be used against "the Enemies of the liberties in America."

On February 25 and 26, there was a lot of activity in Philadelphia. This might have been because Knox's letters arrived. The nationalists had not had much success getting their plans through Congress. They kept using strong words about the army's stability. On March 8, Pennsylvania Colonel Walter Stewart arrived at Newburgh. Stewart knew Robert Morris. They had worked together before when Stewart suggested coordinating activities of private creditors of the government. He knew how bad things were in Philadelphia. Washington had ordered his move to Newburgh (he was returning to duty after being sick). This would not usually draw attention. We don't know much about his movements at camp. But it seems likely he met with General Gates soon after he arrived. Within hours, rumors flew around the Newburgh camp. They said the army would refuse to disband until its demands were met.

Washington's Important Speech

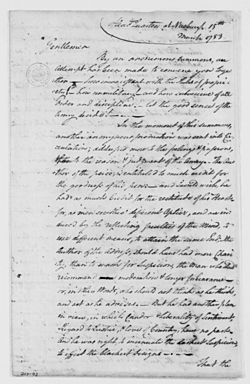

On the morning of March 10, an unsigned letter started circulating in the army camp. Major John Armstrong, Jr., an aide to General Gates, later admitted he wrote it. The letter complained about the army's condition and Congress's lack of support. It called on the army to send Congress a final demand. At the same time, an anonymous call for a meeting of all officers was published. It was set for 11 a.m. the next day.

Washington acted quickly. On the morning of the 11th, in his general orders, he objected to the "disorderly" and "irregular" nature of the anonymously called meeting. He announced that there would be an officers' meeting on the 15th instead. This meeting, he said, would be led by the most senior officer present. Washington asked for a report of the meeting, suggesting he would not attend.

On the morning of the 12th, a second unsigned letter appeared. It claimed Washington's agreement to a meeting meant he supported the plotters. Washington had first thought the first letter was from people outside the camp. He even thought Gouverneur Morris was a likely writer. But he had to admit this was unlikely given how fast the second letter appeared.

The March 15 meeting was held in the "New Building" or "Temple." This was a 40 by 70-foot (12 by 21 m) building at the camp. After General Gates opened the meeting, Washington entered the building, surprising everyone. He asked to speak to the officers. A stunned Gates gave him the floor. Washington could see from his officers' faces that they were very angry. They had not been paid for a long time. They did not show the usual respect they had for Washington.

Washington then gave a short but powerful speech, now called the Newburgh Address. He advised them to be patient. His message was that they should oppose anyone "who wickedly attempts to open the floodgates of civil discord and deluge our rising empire in blood." He then took out a letter from a member of Congress to read to the officers. He looked at it and fumbled with it without speaking. Then he took a pair of reading glasses from his pocket. These were new, and few of the men had seen him wear them. He then said:

Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.

This made the men realize that Washington had sacrificed a great deal for the Revolution, just like them. These were his fellow officers, many of whom had worked closely with him for years. Many of those present were moved to tears. With this act, the conspiracy ended as he read the letter. He then left the room. General Knox and others offered resolutions that stated their loyalty again. Knox and Colonel Brooks were then chosen for a committee to write a proper resolution. Almost the entire group approved the resolution. It expressed "unshaken confidence" in Congress. It also showed "disdain" and "abhorrence" for the irregular proposals published earlier that week. Historian Richard Kohn believes Washington, Knox, and their supporters carefully planned the entire meeting. Only Colonel Timothy Pickering spoke against it. He criticized the group for being hypocritical. They were condemning the anonymous letters that they had been praising just days before.

What Happened Next?

General Washington sent copies of the anonymous letters to Congress. This "alarming intelligence" (as James Madison called it) arrived while Congress was discussing the pension issues. Nationalist leaders arranged for a committee to respond to the news. They purposely filled it with members who were against any pension payment. The pressure worked on Connecticut representative Eliphalet Dyer, one of the committee members. He suggested approving a one-time payment on March 20.

The final agreement was for five years' full pay instead of the lifetime half-pay pension originally promised. The soldiers received government bonds. At the time, these bonds were risky. But the new government in 1790 paid them back at their full value.

The soldiers continued to complain. The unrest spread to the noncommissioned officers (sergeants and corporals). Riots happened, and a mutiny was threatened. Washington rejected ideas that the army should stay together until the states found the money for their pay. On April 19, 1783, his General Orders announced that the fighting against Great Britain had ended. Congress then ordered him to disband the army. Everyone agreed that a large army of 10,000 men was no longer needed. The men were eager to go home.

Congress gave each soldier three months' pay. But since they had no funds, Robert Morris issued $800,000 in personal notes to the soldiers. Many soldiers sold these notes to people who bought them cheaply. Some even sold them before leaving camp, just to get money to go home. Over the next few months, most of the Continental Army was sent home. Many soldiers realized this was basically the army breaking up. The army was officially disbanded in November 1783. Only a small force remained at West Point and a few scattered frontier outposts.

Problems with pay came up again in Philadelphia in June 1783. Because of a misunderstanding, troops in eastern Pennsylvania thought they would be discharged before Morris's notes were given out. They marched to the city in protest. Pennsylvania President John Dickinson refused to call out the local soldiers. He thought they might actually support the protesting soldiers. So Congress decided to move to Princeton, New Jersey. There is some evidence that several people involved in the Newburgh affair (like Walter Stewart, John Armstrong, and Gouverneur Morris) might have played a role in this uprising too.

Many laws have been passed since then to give pensions to veterans of the Revolutionary War. The most famous is the Pension Act of 1832. However, enslaved people who had escaped and fought in the war were denied pensions. One example is Jehu Grant. His pension application after the 1832 act was denied because he was an escaped slave when he served. This was despite him escaping because he feared being forced to serve the British. However, many freed slaves and slaves who joined with their owners' permission did get pensions, like Jeffrey Brace in 1821.

The most important long-term result of the Newburgh affair was a strong confirmation of a key idea: the government (civilians) must control the military. It also removed any idea of a military takeover. This showed that such actions were against the republican values the country stood for. It also proved Washington's strong belief in civilian control over the military.