Norse-American medal facts for kids

| United States | |

| Diameter |

|

|---|---|

| Thickness |

|

| Edge | plain |

| Composition |

|

| Years of minting | 1925 |

| Mintage |

|

| Mint marks | None, all pieces struck at Philadelphia Mint without mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

|

|

|

| Design | Viking warrior |

| Designer | James Earle Fraser |

| Design date | 1925 |

| Reverse | |

|

|

|

| Design | Viking longship |

| Designer | James Earle Fraser |

| Design date | 1925 |

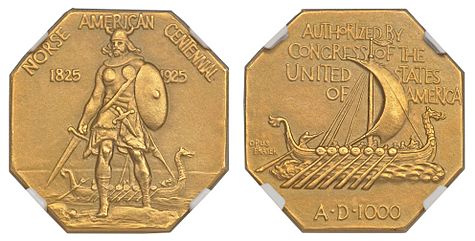

The Norse-American medal was made in 1925 at the Philadelphia Mint. It was created to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ship Restauration. This ship brought some of the first Norwegian immigrants to the United States.

U.S. Representative Ole Juulson Kvale from Minnesota was a proud Norse-American. He wanted a special coin to mark the Restauration's journey. When the Treasury Department said no to a coin, he decided on a medal instead. The famous sculptor James Earle Fraser, who designed the Buffalo nickel, created the medal. It honors the Viking heritage of these immigrants. The front of the medal shows a Viking warrior, and the back shows his ship. The medals also remind us of the early Viking explorations in North America.

After the Congress approved it, the medals were made in different metals and sizes. Most were ready before the celebrations in Minneapolis in June 1925. Only 53 gold medals were made, and they are very rare and valuable today. The silver and bronze medals are not as valuable. Sometimes, people collect these medals as part of the U.S. commemorative coin series.

Contents

Why the Norse-American Medal Was Created

On July 4 or 5, 1825, the ship Restauration left Stavanger, Norway. It carried 45 people who were moving to the United States. When they arrived in New York on October 9, the ship was stopped. It had too many passengers for its size.

President John Quincy Adams pardoned the immigrants. This meant they did not have to pay a fine. They did not speak English and did not know American laws. These passengers were the first of many Norse-Americans to cross the Atlantic. They settled mostly in the northern and western United States.

A Congressman's Idea for a Commemorative Medal

Ole Juulson Kvale was a congressman from Minnesota. He was a member of the Norse-American Centennial Commission. This group planned the 100th anniversary celebration of the Restauration's voyage. This event was important for Norse-Americans. They wanted to show their ethnic pride and how they fit into American society.

In January 1925, Kvale asked the Treasury Department for a commemorative coin. He was told they would not support it. At that time, Congress was not likely to approve coins for ethnic groups. This was because of a controversy over a 1924 coin.

Kvale then learned about the Mint making medals. He met with Treasury officials. He suggested making the medal octagonal or hexagonal. This idea was liked by officials. Kvale also worked to get commemorative stamps issued. He said the medal and stamps honored the Vikings' explorations around the year 1000. Kvale wanted to help "preserve" Norwegian heritage in metal and paper.

How the Medal Became Law

Congressman Kvale introduced a bill for the Norse-American medal. This happened in the House of Representatives on February 4, 1925. The bill was sent to a special committee. On February 10, Kvale reported that the committee approved the bill.

He said that 40,000 medals would be made. The government would not have to pay for them. Treasury officials also supported the bill. Kvale explained that the medal was important for the many descendants of Norse immigrants. It was also important for Minnesota and the "great Northwest."

Senator Peter Norbeck of South Dakota also introduced a similar bill. His bill passed the Senate on February 18. This Senate-approved bill then went to the House of Representatives. On February 27, the House discussed it.

Congressman Kvale confirmed that the Treasury Secretary supported the bill. The House then approved the bill without any changes. President Calvin Coolidge signed it into law on March 2, 1925.

The law allowed up to 40,000 medals to be made. They would be struck at the Philadelphia Mint. The Norse-American Centennial Commission would pay for the cost of making them.

Creating the Medal's Look

Kvale hoped that sculptor Gutzon Borglum would design the medal. Borglum was very busy with the Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar and later Mount Rushmore. He could not take on the work. So, James Earle Fraser, who designed the Buffalo nickel, was hired. He was paid $1,500, which was a normal fee for such work.

Fraser created the designs and sent them to the Mint. The designs were approved. The only change suggested was to remove a small word from the back of the medal. Sketches of the designs were printed in a newspaper. Some people thought the design made it seem like Norwegians still dressed like Vikings in 1825. These public comments did not change the design.

What the Medal Looks Like

The front of the medal shows a Norwegian Viking chieftain. He has just landed from his ship, which is seen behind him. He is ready for battle with a horned helmet, shield, sword, and dagger. He is meant to be landing at Vinland. This was a place in the Americas explored by Vikings around the year 1000. The horned helmet is probably not historically accurate for that time. The medal also shows the centennial dates.

The back of the medal shows a Viking ship. It also states that Congress authorized the medal and shows the approximate year Vinland was settled. The artist's signature, "OPUS FRASER" (Fraser's work), is on the left side of the ship.

Some people wonder if Leif Erikson, a famous Viking explorer, would have been a better choice. But Congressman Kvale wanted a more romantic image. He liked the idea of a Viking ship and a chieftain in full gear.

The medal does not focus on the Restauration's arrival in the United States. Instead, it celebrates the pride in the early Viking explorers. One of the stamps for the celebration shows a Viking ship, and the other shows the Restauration. These government items honored Norwegian immigrant heritage. They also suggested that Norwegians were the first Europeans to land in America.

Making and Selling the Medals

Six thousand silver medals were made between May 21 and 23, 1925. These were thin medals. They were handled like regular coins and sent to a bank for the centennial commission. Between May 29 and June 13, 33,750 thicker silver medals were made. The reason for two types of silver medals is not clear.

One hundred gold medals were made on June 3 and 4. Congressman Kvale received the second one. The thin silver medals cost the commission 30 cents each. The thick ones cost 45 cents, and the gold ones cost $10.14. The thick silver medals were sold for $1.25, and the gold ones for about $20.

The medals were sold by mail order. None were sold at the celebrations in person. People could buy only one medal for themselves. However, they could buy more for family members. The thin medals were sold later, mostly to coin collectors. Many "Norsemen" did not buy the medals. After the celebrations, Kvale tried to sell 5,000 medals in New York, but he was not successful. Of the 100 gold pieces, 47 were returned to the Treasury because they could not be sold. Some silver medals were also returned.

The Centennial Celebration

The Norse-American Immigration Centennial Celebration was held near Minneapolis. It took place from June 6–9, 1925. People came from far away in car caravans. President Coolidge attended the event. He called the Viking explorers "sons of Thor and Odin." He praised the Norwegian people.

The New York Times noted that special stamps and a medal were issued for the celebration. The newspaper said it was rare for the government to honor such an event so much.

The Times incorrectly said it was the first commemorative medal from the Mint. Later, it was found that a medal for American independence was made in 1876. Congressman Kvale learned about this older medal. He liked that it was made in a larger size. He thought a larger size would show the details of his medal better. Between 60 and 75 of these larger bronze medals were made. They were plated in silver by a private company. About 30 were given to important people, including President Coolidge.

The Norse-American medal is not a coin. It is not legal tender, meaning it cannot be used as money. But because it looks like a coin and was approved by Congress, collectors sometimes include it with U.S. commemorative coins. Silver medals can be bought for less than $100 to $500. The silver-plated bronze ones can cost between $500 and $3,500. A gold medal has sold for as much as $40,000. Some medals show damage because they were carried in pockets or worn.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |