North Channel Naval Duel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Channel naval duel |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American War of Independence | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Paul Jones | George Burdon † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| USS Ranger (sloop of war), 18 guns |

HMS Drake (sloop of war), 20 guns (officially 16) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 killed, 5 wounded | 5 killed, 20 wounded, HMS Drake severely damaged | ||||||

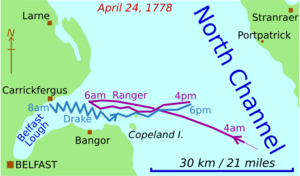

The North Channel naval duel was a sea battle between two ships. It happened on April 24, 1778. The American ship Ranger fought the British ship Drake. This fight took place in the North Channel. This channel separates Ireland from Scotland.

This battle was the first time American ships won a victory in the Atlantic. It was also one of the few American naval wins in the Revolutionary War. The Americans won without having a much stronger force. This battle was part of John Paul Jones's plan to bring the war to British waters.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The American Revolutionary War was not just fought in America. Naval battles happened all over the Atlantic. American ships, including privateers (privately owned armed ships), attacked British merchant ships. They took these captured ships to French ports. France was officially neutral then, but they helped the Americans.

These American successes encouraged France. In February 1778, France signed treaties with America. This made Britain worry about a French attack. The British Royal Navy had to send many ships to the English Channel. This left other areas, like the Irish Sea, less protected.

American captains had shown that ships could enter the Irish Sea. They could cause trouble for ships trading between Britain and Ireland. John Paul Jones wanted to show the British people that war could come to their own shores. He wanted to make them understand what Americans faced.

The Ranger Mission

John Paul Jones sailed from France on April 10, 1778. He was on the small American ship, the Ranger. He first tried to raid the port of Whitehaven in Cumberland, England. This happened on the night of April 17–18. He then bothered ships in the North Channel.

On April 20–21, Ranger entered Belfast Lough in northern Ireland. Jones wanted to capture the British ship HMS Drake. It was anchored near Carrickfergus. He was not successful that time. He returned to Whitehaven and set fire to a merchant ship.

Soon after, he raided the home of the Earl of Selkirk in Scotland. News of these attacks spread quickly. But Ranger was already heading back to Carrickfergus.

The Day of the Battle: April 24, 1778

Getting Ready for the Fight

John Paul Jones's crew hoped to get rich by capturing British merchant ships. But Jones had sunk more ships than he captured. This meant less money for his crew. They were not happy. Now, Jones wanted to capture a Royal Navy ship. This ship had no cargo to sell.

Jones later wrote that his crew was very upset. They were reluctant to fight. The wind and tide also made it hard to enter the harbor. But then, Drake started to leave port. This made the American crew feel better.

Drake had been getting ready since Ranger's first visit. They took on about 60 volunteers from Carrickfergus. This boosted their crew to about 160 men. Many of these were "landsmen," meaning they were not experienced sailors. They were mainly for close fighting.

Drake set sail around 8 AM. But the wind and tide were against them. They moved very slowly. After an hour, a small boat from Drake went to check out Ranger. Jones hid most of his crew and big guns. This trick worked. The British reconnaissance crew was captured. This cheered up the Americans. They learned that Drake had many new volunteers.

Around 1 PM, Drake slowly moved across Belfast Lough. Another volunteer, Lieutenant William Dobbs, came aboard Drake. He was a local man who had just gotten married. He brought news from Whitehaven about Ranger.

In the afternoon, the wind and tide became better. Ranger slowly moved out of the Lough into the North Channel. Jones made sure to stay close to Drake. Finally, around 6 PM, the two ships were close enough to talk. Jones flew the American flag. Lieutenant Dobbs asked what ship it was. Jones told him the truth.

The Drake was originally a merchant ship. The Royal Navy bought it to fill a gap in their fleet. Its 20 guns were not even official Navy weapons. The ship's hull was not good for quick turns or resisting cannon fire. Ranger was built as a fighting ship. Jones had made it even better. It had 18 six-pound guns. This meant Rangers total firepower was a bit stronger. But Drakes many volunteers meant they could try to board Ranger and fight hand-to-hand.

The Battle Begins

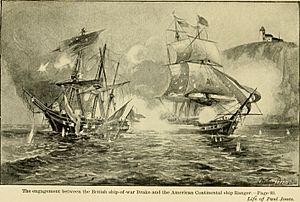

After the formal greetings, Ranger quickly turned and fired its guns at Drake. The British could not fire back right away. When they did, they had problems. Their four-pound guns were unstable when fired. They would tip forward, which was dangerous for the gun crews.

After a few more shots, more problems appeared for Drake. A piece of metal from Ranger's third shot hit Lieutenant Dobbs in the head. He was badly injured. The young boys who carried gunpowder to the guns were scared. They did not want to do their job. The ship's master had to tell the acting gunner to hurry up. Also, the slow matches used to fire the guns kept going out.

Drake's small guns could not break through Rangers strong hull. So, Drake tried to aim at Rangers masts, sails, and ropes. They wanted to slow the American ship down.

The ships were very close, but they never got close enough to grapple and board. John Paul Jones knew about the extra men on Drake. Both sides also fired small guns at each other. Here, Drake was also at a disadvantage. They ran out of paper for their cartridges. So, their musketeers had to slowly load their guns with loose powder and shot.

Drake killed only one of Jones's crew, Lieutenant Samuel Wallingford. Two others died from a cannon shot. Five of Drake's crew were killed. This included Captain Burdon himself. He was hit in the head by a musket ball. With both the captain and lieutenant out of action, the master, John Walsh, took command.

By this time, Drakes sails and ropes were torn to pieces. Its masts were also badly damaged. The ship could barely move. It could not even turn to aim its guns. The small-arms fighters had retreated. Only about a dozen people were left on Drakes main deck. A few minutes after the captain died, the remaining officers told the master they should surrender. The ship's flag had already been shot away. So, Mr. Walsh had to shout and wave his hat to surrender. John Paul Jones recorded that the battle lasted one hour and five minutes.

What Happened After

Thirty-five men from Ranger went to Drake to take control and check the damage. For the next three days, they repaired Drake while slowly sailing north-west. They captured a cargo ship that came too close. This ship was used for extra space.

Six Irish fishermen who had been captured earlier were allowed to go home. They took three sick Irish sailors with them. Jones also gave them sails from Drake and some money. When they returned, they reported that Jones was worried about Lieutenant Dobbs, who was still very ill. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy sent warships to chase them. But they never found the Americans.

News of the battle reached France quickly. The Americans were welcomed as heroes. The British learned a hard lesson. Their navy could not protect their ships, coasts, or even their own fighting vessels from American raiders. Militia groups were sent to coastal areas. Seaports got artillery to defend themselves. People formed volunteer groups to help defend their land.

From then on, the newspapers paid close attention to John Paul Jones. They tried to understand how he could be both a feared enemy and a chivalrous leader. He even wrote kind letters to the Earl of Selkirk and Lieutenant Dobbs's family.

John Paul Jones became famous around the world. The naval duel in the North Channel was a great success for his mission. It showed that even the world's most powerful nation could be attacked. News of his next mission created fear and uncertainty. This helped make his return visit in 1779 his most famous achievement.

Sources

- Bradbury, David "Captain Jones's Irish Sea Cruize", Whitehaven UK, Past Presented, 2005, ISBN: 978-1-904367-22-2

- Sawtelle, Joseph G. (Ed.) "John Paul Jones and the Ranger", Portsmouth NH, Portsmouth marine Society, 1994, ISBN: 0-915819-19-8. This book has the full log of the 1777–1778 voyage, the diary of surgeon Ezra Green, and many letters by Jones and others.

- Bradford, James (Ed) "The Papers of John Paul Jones" microfilm edition, ProQuest (Chadwyck-Healey), 1986. This set includes all known papers by or to Jones, like letters, reports, and ship logs.