Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene |

|

|---|---|

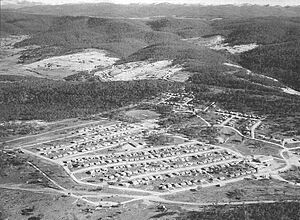

Adaminaby, undated

|

|

| Location | Eucumbene, Snowy Valleys Council, New South Wales, Australia |

| Built | 1956-1958 (dam) |

| Architect | Eucumbene dam: Snowy Hydro Electric Authority |

| Owner | Snowy Hydro Limited |

| Official name: Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene, including relics and movable objects; Eucumbene River; Eucumbene Valley; Old Adaminaby Remains; Old Adaminaby Ruins; Old Adaminaby Drowned Landscape | |

| Type | state heritage (archaeological-terrestrial) |

| Designated | 3 June 2008 |

| Reference no. | 1794 |

| Type | Townscape |

| Category | Urban Area |

| Builders | Eucumbene dam: Snowy Hydro Electric Authority |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Old Adaminaby was a town in New South Wales, Australia. It was established in 1830. Today, it lies beneath the waters of Lake Eucumbene. This lake is a huge reservoir created by the Eucumbene Dam. The dam was built between 1956 and 1958.

The area is also known by other names. These include the Eucumbene River and the Eucumbene Valley. It is also called Old Adaminaby Remains or Old Adaminaby Drowned Landscape. The land is owned by Snowy Hydro Limited. This company is owned by the Australian, New South Wales, and Victorian governments. The site was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register in 2008.

Contents

- A Look Back: History of the Area

- First People: Indigenous History

- Early Settlers: Pastoral Life (1827-1957)

- Growing Up: The Town of Old Adaminaby (1859-1949)

- Connecting Places: Roads and Bridges

- Working Hard: Industrial Development

- A Big Project: The Snowy Scheme (1949-1973)

- Moving a Town: Relocating Adaminaby (1956-1957)

- Lake Eucumbene: Today (1957-Present)

- What Remains: Description of the Site

- Condition of the Site

- Why It's Important: Heritage Listing

- Images for kids

A Look Back: History of the Area

First People: Indigenous History

The Ngarigo people lived in this area for thousands of years. Their land stretched from Canberra south to the Victorian border. It went west to Tumbarumba and east to the coast. The Ngarigo were named after the plains turkey, a bird common in the Monaro grasslands.

Different Ngarigo clans had special rights to parts of the land. The Bemerangal clan looked after the area where Adaminaby is now. They traveled to the coast seasonally, following old routes. High mountains were important meeting places for many groups. Large camps were set up in places like Adaminaby and Jindabyne. Here, groups gathered for summer hunting and ceremonies.

When the Eucumbene and Jindabyne valleys were flooded, many campsites were covered. But many stone tools can still be found around the lake edges. This shows that people also camped higher up the valley sides. This helped them avoid the cold air in the valleys. When Europeans arrived, many Ngarigo people died from disease and violence. Most were forced off their land. Some stayed to work on properties and care for their country.

Early Settlers: Pastoral Life (1827-1957)

The first European settlers came to the Monaro in 1827. They were attracted by the wide-open grasslands. Richard Brooks brought cattle to the Eucumbene valley and Adaminaby Plain. By 1831, others like William Faithfull joined him.

In 1848, Charles York and Henry Cosgrove applied for the "Adumindumee" land. George Young Mould, a doctor, arrived in 1846. In 1853, he started his property called Boconnoc in the Eucumbene valley. He also opened one of the first stores in Old Adaminaby in 1862. The Mould family lived at Boconnoc homestead until the 1950s.

Many other families farmed the land for generations. These included the Herberts, Reynolds, and Mackays. Some early properties were at Old Adaminaby, Eucumbene, and Buckenderra. Later, places like Studlands and Warwick were built. Most farms were on the eastern side of the Eucumbene River. This side had open, flat land.

Farmers used lower pastures for winter grazing. In summer, they moved their animals to higher country. These areas were called "snow leases." This practice of moving animals to different pastures is called transhumance. It was very important for farmers in the Snowy Mountains.

Growing Up: The Town of Old Adaminaby (1859-1949)

By 1859, Charles York had left Adaminaby. His stockmen lived in a few huts near the Eucumbene River. In 1859, gold was found at nearby Kiandra. Thousands of miners traveled through the small settlement. It became a stopping point for travelers.

In 1860, Joseph Chalker built the first hotel there. A post office and two stores soon followed. The hamlet was first known as Chalker's. In 1861, a village was surveyed and named Seymour. Joseph Chalker bought the first land blocks. The town grew steadily because of the gold rush. By 1877, it had 400 people, three hotels, and three stores.

In 1886, the name was changed to Adaminaby. This was to avoid confusion with Seymour in Victoria. Adaminaby became a busy town. It was supported by local farmers and travelers. By 1892, it had five general stores, two butchers, and a baker. A butter factory was built in 1895.

By the early 1900s, Adaminaby had a picture theatre and a racecourse. The Kyloe Copper Mine also helped the town's economy. Adaminaby was growing fast. By the 1920s, it had a watchmaker, cafes, a hospital, and two schools. The population in the 1940s was 750 people.

Old Adaminaby grew over its century of life. But it never had modern services. There was no electricity, water supply, or sewerage system. People used kerosene lamps and candles for light. Rainwater was collected in tanks. Residents remembered it as a friendly community. Winters were "harsh, cold, wet and windy." Heavy snowfalls were common.

Connecting Places: Roads and Bridges

In the mid-1850s, better roads and bridges were needed. Local communities wanted proper ways to cross creeks and rivers. Most bridges were simple and made of hardwood. The "truss system" became a good option. It used strong timber designs.

John A. McDonald designed a new timber truss bridge in 1879. It was easier and cheaper to build and maintain. This design became known as the McDonald Truss. Many of these bridges were built. A McDonald Truss bridge was built over the Snowy River at Jindabyne in 1893.

The Six Mile Bridge crossed the Eucumbene River. It was likely built around the same time. It was also a McDonald type truss design. This bridge was used for half a century. In 1957, parts of it were removed. People expected it to collapse, but it didn't. They even tried to burn it down, but it resisted. The bridge stayed standing as the waters rose around it.

Old roads linked farms and settlements. Adaminaby was a key junction for roads from Cooma and Jindabyne. When the Eucumbene River was dammed, these old routes were cut. This separated some communities and changed how people interacted.

Working Hard: Industrial Development

Two major mining booms helped Adaminaby grow. The first was the gold rush at Kiandra in 1859. Thousands of miners passed through Old Adaminaby. The gold rush only lasted a few years. The harsh environment and low returns led to Kiandra being deserted by 1860.

In 1900, a gold dredging company started operations at Kiandra. Their work lasted three years. At the same time, copper was found at Kyloe. This was across the Eucumbene River from Old Adaminaby. A mine shaft was dug in 1872. But real work didn't start until 1901.

The Shaeffer Bros took over the mine in 1904. They sent copper ore to a smelting company. In 1907, the Kyloe Mining Company bought the mine. They improved the site and built furnaces. Adaminaby became a busy center because of the copper mining.

By 1910, 110 men and boys worked at the Kyloe mine. This number grew to 195. Electric lights allowed mining 24 hours a day. In 1910, a huge 23-ton boiler was brought to the mine. It took 76 bullocks and six weeks to move it 50 kilometers from Cooma.

By April 1913, the mine's ore was used up. The Kyloe mine was abandoned. The boiler was taken apart. When Lake Eucumbene filled, most of the Kyloe mining site was covered. But many old items have reappeared as the water levels have dropped.

A Big Project: The Snowy Scheme (1949-1973)

People first talked about using melted snow from the Snowy River in the mid-1800s. They wanted to divert the water to help with droughts. In 1884, a plan was made to send Snowy River water to the Murrumbidgee River.

After World War I, there were power shortages. A new idea was to use the Snowy River to make hydro-electricity. This would power Sydney. By 1940, the NSW Government studied a detailed plan.

In 1949, the Australian government passed the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Power Act. The Snowy Scheme was considered a huge engineering feat. It is still one of the world's greatest engineering achievements. It is compared to the Suez Canal and Panama Canal.

The Scheme had two main parts. One part diverted the Snowy River. The other part involved damming the Eucumbene River. This water storage was first called Adaminaby Dam. It was seen as the heart of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. Later, its name was changed to Eucumbene Dam, or Lake Eucumbene.

In 1949, a ceremony was held near Old Adaminaby. The Governor General, Sir William McKell, set off an explosive charge. The Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, and other important people were there. About 1,200 guests attended, including most people from the old town. A plaque was put up near the proposed dam wall.

At first, the dam waters were only supposed to rise below the town. Some buildings would be moved to higher ground. But further studies showed that building the dam wall 6 kilometers further down the valley would hold much more water. This new plan was more expensive but worth it. The dam wall was built at the new spot. Works for the extra capacity were finished in 1967. The original ceremonial plaque ended up under many meters of water.

During the Snowy Scheme, 120 camp sites were built. Four of these are now under Lake Eucumbene's high water mark. These include Adaminaby Portal Camp and Adaminaby Transit Camp. Coles's Camp and Eucumbene Portal Camp were also submerged.

The first camp, Adaminaby Portal Camp, was built in 1949. It was abandoned in 1953 when the new dam wall was planned. A more permanent camp was set up at Eaglehawk near the dam.

Moving a Town: Relocating Adaminaby (1956-1957)

The new dam meant that the Eucumbene valley and most of Adaminaby would be flooded. This was a huge area of about 24,500 hectares. Homes, businesses, and valuable farmland would be lost. People worried about getting fair payment for their properties and lost work. Most residents did not want to move.

Some people thought the forced land takeover was illegal. Farmers formed the Graziers Protection Association. They got legal advice that the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Power Act might not be valid.

The Authority wanted to avoid lawsuits. They agreed to buy land at market rates. They also offered a 3-year lease-back option. This gave farmers time to find new properties. Most farmers moved away because there was little land to buy.

Professor Denis Winston, the Authority's town planner, designed a new town. Residents could choose from three locations. They chose a spot on the main road, called Bolairo View. They gave up lake views for a secure future on the highway. They also liked that the new site was warmer and more sheltered.

In 1954, residents voted for the new location. This was the Authority's first time moving a whole community. Many families had lived and worked in Old Adaminaby for generations. The old town had Victorian buildings, shops, hotels, and houses. It was a typical Australian rural town.

The Authority tried to make the move as easy as possible. If people wanted to move elsewhere, the Authority bought their property. They also gave money for moving costs. If people wanted to move their buildings, the Authority paid for it. They also paid for temporary housing. If people wanted a new building, the Authority provided one.

The Authority built a new town with a modern shopping center, hotel, and theatre. It also had two schools, sports clubs, and a racecourse. Thousands of trees were planted, and new roads were built. Modern services like electricity, water, and sewerage were added. The old town did not have these.

The first house was moved in 1956. Within 18 months, all buildings to be moved were gone. Weatherboard buildings were slowly transported. There were problems with wet weather and snow. Some structures had accidents along the way. Two brick and stone churches were taken apart and rebuilt. In total, 102 buildings were moved from Old Adaminaby. Most went to the new town.

The flooding was a difficult time for local residents. There was much sadness and anger about losing homes and farms. People also felt that their old social connections were broken. These feelings are still present today. Some families stayed until the water was at their doorsteps. The Authority warned that the lake could rise quickly. People had to leave many items behind when roads were cut off.

Lake Eucumbene reached its full capacity in 1973. But when the Snowy Scheme was fully working, the water level was lowered. The new Adaminaby was cut off from old routes to Jindabyne and Cooma. Good grazing land was lost, and jobs decreased. About half the town's population left due to lack of jobs. The old town blocks were large, but the new ones were much smaller.

Jindabyne was another town flooded by the Scheme. It had 250 residents. When it was time to move Jindabyne, the Authority had learned from Adaminaby. They made the process simpler. Residents had less say in the new town site. But the Authority involved them in the town's design. They also collected historical records. The new Jindabyne overlooked the newly created Lake Jindabyne. No buildings were moved there. The process was handled more positively than in Adaminaby.

Lake Eucumbene: Today (1957-Present)

Lake Eucumbene became popular for water sports. Many tourism businesses started around its shores. It was also stocked with trout, making it a popular fishing spot. Several areas were set aside for holiday cabins.

An unexpected problem was that native animals got trapped on islands as the water rose. People remember islands covered with kangaroos and snakes. There were attempts to move the kangaroos, but success was limited. Sir Edward Hallstrom and Sir William Hudson created a kangaroo refuge on one island. This became known as Hallstrom Island. It housed albino kangaroos and Great Eastern Grey kangaroos.

The Authority promoted Hallstrom Island and Grace Lea Island as tourist attractions. People could take a boat from Old Adaminaby to visit the animals. The refuges closed in 1987 after animals were illegally killed.

Since 1996, the Monaro region has had a long drought. Water levels in Lake Eucumbene have been very low. In June 2007, the lake dropped to a record low of 10% capacity. This low water level has attracted sightseers. But it has reduced the number of fishermen.

When the lake levels were low in the early 1980s, many old items appeared. At that time, no one removed them. But in 2007, many large objects were taken. These included old farm machinery and even a stone-and-brick house. The community became worried about these removals. The Snowy River Shire asked for a special heritage order. This order would stop people from interfering with the site. The order was put in place in June 2008. Signs were put up to warn the public that removing items was illegal.

What Remains: Description of the Site

The remains of Old Adaminaby are on the bottom of Lake Eucumbene. They can be grouped into five types of relics:

- Old Adaminaby: Building foundations, old household items, car parts, old plants.

- Pastoral: Farmhouse foundations, farming machines, fence posts, gardens, graves.

- Industrial: Mining buildings, waste piles, shafts, old boilers.

- Roads & Bridges: Main roads, tracks, the Six Mile Bridge.

- Snowy Scheme: Camp foundations, rubbish dumps, car parts, discarded work items.

Old Adaminaby Town Remains

When the lake waters rose, valuable items were moved. Only abandoned and useless objects were left behind. Bulldozers flattened many old buildings. Concrete slabs, bricks, and stones show where buildings once stood. Old vehicles, stoves, and household items were left behind.

Many movable items have been stolen. But piles of rubble and foundations still show where buildings and streets were. When lake levels are low, you can see steps of old churches and schools. You can also see foundations of the post office and other buildings.

Four buildings from Old Adaminaby were on higher ground. They were not flooded and are still standing. The cemetery was also on a hill and was not covered by water. These four buildings and the cemetery are not part of the heritage site:

- The old Methodist Church, now a community hall.

- The old public school, now an office.

- Denison Cottage, a brick house for holiday rentals.

- The old Police Station and Courthouse, now a private home. This concrete building was moved further up the hill.

Farm Sites and Relics

Braemar

James Holston built Braemar, a stone and brick house and post office. It was abandoned in the 1950s and covered by Lake Eucumbene. It reappeared during low lake levels in the 1980s. Recently, this 140-year-old house was taken apart. All the stones and bricks were illegally removed. Only old fruit trees and a fuel stove remain.

Burnside

Burnside was a weatherboard farmhouse. It had a separate kitchen. Later, a new kitchen was built onto the main house. It was made of local stone and bricks. Today, the kitchen fireplace and chimney remain. You can also see old timber fence posts and parts of farm machinery.

Boconnoc and Buckenderra

The Boconnoc homestead site is now overgrown. It has been out of the lake water for many years. You can find it by looking for old elm and pine trees. These were part of a large garden with fruit trees. Stones and bricks show where the house was. The Authority demolished it in the 1970s.

Four family graves at Boconnoc were not moved before the lake filled. Over 50 years, the graves were covered and uncovered by water. This caused damage to the headstones and stone walls. In 1998, an agreement was made to protect the graves. The headstones were removed, and the graves were covered in concrete. Stones from the walls were used to build protective banks.

An old stone sheep dip has reappeared near Buckenderra Creek. It was used to wash sheep. It is made of granite, suggesting it is very old.

Tryvilla

Only a brick tank stand and some foundations remain of Tryvilla. Old maps show three buildings were once here. The Delany family owned this land since 1866. The homestead was demolished in the 1950s. The foundations suggest it was built in the early 1900s.

Eucumbene

The Eucumbene property dates back to the 1840s. In the 1850s, it was the only farmhouse between Cooma and Adaminaby. The Herbert family bought it in the early 1900s. They built a new homestead in 1930. The old one was taken down in 1943. In 1955, the 1930 homestead was also demolished as the lake waters rose.

Hemsby

Hemsby was another property owned by the Mackay family. They had been in the area since 1861. George Watkins Mackay bought Hemsby in 1912. He built a weatherboard house with a corrugated iron roof. It had many outbuildings. The house was later extended with bricks. It was known for its large, formal garden.

Industrial Sites and Relics

Kyloe Copper Mine

Most of the Kyloe mine was submerged. But three main sites were visible near the water's edge. In 1995-96, concrete pillars, slabs, and a stone track could be seen. About 300 meters away, an old boiler and other items showed a processing site. There was also a waste dump and a brick floor where smelters were.

In January 2007, many more items appeared as the lake water dropped. These included concrete slabs, machinery parts, mine shafts, and a rubbish dump.

Waterous Steam Engine

This old steam engine lies in the silt at the lake's edge. It is between Old Adaminaby and Anglers Reach. Some people thought it pumped water to the mine. But it is likely it was used on a farm. It might have powered shearing or chaff-cutting equipment.

The engine has "Waterous Brantford" stamped on it. It was built by the Waterous Engine Works in Canada. This model was called the Champion type. It had a special vertical boiler. It could make steam very quickly. Only a few of these 1800 engines are known to exist today. There are only two others in Australia. One is still working in Inverell, NSW. The other is in pieces. Only one other is known in the rest of the world.

Snowy Scheme Camp Sites and Relics

Two of the four Snowy Scheme camp sites have been seen since the lake levels dropped. These are the Eucumbene Portal Camp and the Adaminaby Portal Camp.

At the Adaminaby Portal site, a well-made road goes through the camp. You can see two large shower and toilet blocks. There is also a separate laundry block. Concrete steps lead up a hill to where huts might have been. Bottles found here are stamped 1952 and 1953. This suggests the camp closed in 1953.

The Eucumbene Portal camp was built for contractors. It seemed to have better housing. This site ended up partly under water. Old beer bottles from the rubbish dump are stamped 1957. This shows the camp closed around that year. Other items in the dump include boots, shoes, and helmets. There is also an old vehicle chassis with wooden wheels. Tons of granite rock from the tunnel are dumped here. The camp site has terra cotta drainage pipes. One building was used as a scout hall until recently.

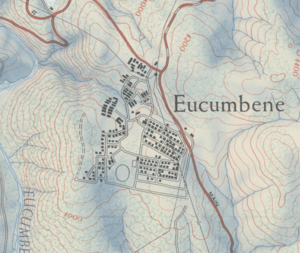

Eucumbene / Eaglehawk Camp

The Eaglehawk construction camp was built in 1953. It was about two kilometers south-east of the Eucumbene Dam site. In 1955, its name changed to Eucumbene. This was to avoid confusion with a town in Victoria. It operated until 1966. It was the largest and longest-lasting construction camp for the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

The camp housed workers and their families. They built the Eucumbene Dam and the Eucumbene-Snowy tunnel. Eucumbene was like a town. It had over 2,000 people at its busiest. The NSW Public Works Department built it.

Eucumbene had a shopping center. It included a general store, petrol station, butcher, and post office. There was a large dining hall for workers and tourists. It also had two churches and a school. A photo from 1954 shows many students at the "Eagle Hawk" Public School.

The camp had a sports area. This included a football field and tennis courts. There was a large work area for repairing trucks and machinery. The town had piped water and a sewage system.

After the tunnel work finished, most houses were moved to other camps. Larger buildings were sold. The town hall was moved to Talbingo. Two permanent houses for engineers remain today. Some sheds are also left in the old work area.

Many old items from the town can still be found. These include roads, the sewage system, and fire hydrants. You can also see foundations of the school, sports area, and houses. The land where Eucumbene stood is now privately owned.

Hallstrom Island

A few yards and sheds remain on Hallstrom Island. These are above the high water mark. They are evidence of the old animal refuge. You can also see parts of the 2.5-meter high kangaroo fence. This fence was built to keep kangaroos on the island. But many reports say the animals swam to the mainland when water was low.

Condition of the Site

As of 2008, the condition of the old items was poor. They had been underwater for many years. Then they were exposed to weather, wind, and waves. The lake started filling in 1957 and was full by 1973. Until recently, the lake was usually 80% full. But in June 2007, due to a severe drought, it dropped to a record low of 10%.

This low level revealed many parts of Old Adaminaby. It also showed parts of the surrounding farms, old industrial sites, and construction camps. In January 2008, Lake Eucumbene was at 20% capacity.

Even though the items are not perfectly preserved, they are still very important. It is amazing that this collection can still be seen and studied today. There is enough left to learn a lot about the past.

Changes Over Time

- 1956-1957: 100 houses and two churches were moved from Old Adaminaby.

- 1957: The Snowy Hydro Electric Authority demolished buildings that would be flooded.

- 1957: The Eucumbene valley began to flood, creating Lake Eucumbene.

- 1958: Construction of Eucumbene Dam was finished.

- 1959: Water reached the edge of Old Adaminaby.

- 1973: Lake Eucumbene was completely full.

- June 2007: Lake Eucumbene reached a record low level of 10% capacity.

Why It's Important: Heritage Listing

As of 2008, the remains of Old Adaminaby and the surrounding area are very important to the state's heritage. They show over a century of farming, town growth, copper mining, and worker camps. They also show how people lived, traded, traveled, and connected. All of this was suddenly covered by water in 1957.

Lake Eucumbene was the first and largest dam in the Snowy Scheme. This Scheme was one of Australia's greatest engineering achievements. It showed the country's hope for the future after World War II. It was a huge project for Australia's history and economy.

The flooding of the Eucumbene Valley and Adaminaby gained national attention. People all over Australia followed the story of the town's relocation. The exposed remains of Old Adaminaby are important. They are linked to the people who were forced to move. These people and their families still feel a sense of loss. The remains show a way of life that ended suddenly. They represent a special part of the Snowy Scheme's history for the displaced community.

These places and items can teach us more about the past. They can show us how farming, towns, and industries developed in the valley. They also provide evidence of events that shaped Australia's economy and people's lives.

Only two towns were purposely flooded for the Snowy Scheme. Adaminaby was the larger and more important one. More people were affected by the flooding of Lake Eucumbene. It is surprising and special that the sites of Old Adaminaby have reappeared after 50 years. This makes them very important to the families and the wider community.

One item found, the Waterous steam engine, is very rare worldwide. Only two other complete examples are known. One is in Inverell, NSW, and the other is in the Northern Hemisphere.

Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register in 2008.

Showing History: Cultural Significance

The site of Old Adaminaby shows a major part of New South Wales's history. It represents over a century of development for the town and surrounding farms. It shows 130 years of a rich farming industry. It also shows the growth of a busy small town from just three huts. All these ways of life ended suddenly in 1957 when the Eucumbene valley was flooded.

The site also shows other past activities. These include copper mining and processing in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It also shows the worker camps for the Snowy Scheme. The flooding of Old Adaminaby is linked to the important Snowy Scheme. Lake Eucumbene was the first and largest of 16 dams. It provided water for farming and hydro-electric power to three states. The Snowy Scheme is a legendary part of Australia's history. It is one of only two sites in Australia recognized as an international Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Community Connections: Social Significance

This site is important because of its strong link to the community of displaced people from 1957. It is also important to their families today. The people who were forced to move from the Eucumbene Valley and Old Adaminaby care deeply about their past. They remember the events that changed their lives so much.

Many people in this community still feel sadness and anger about being moved. They also feel upset about how it was handled. When the submerged sites appeared again during the recent drought, it brought back these feelings. The illegal removal of some items in 2007 made these feelings stronger.

The site is also important to people beyond those directly affected. The story of the land takeovers and relocations was followed across Australia in the 1950s. Public interest has grown again with the reappearance of the old items.

Learning from the Past: Research Potential

The items found at Old Adaminaby and the surrounding areas can teach us a lot. They show over a century of farm life, town growth, and mining. They also show the lives and working conditions of men who built the Snowy Scheme. These items represent old ways of life that ended suddenly and unusually.

They serve as a guide for how the Scheme was built. They also show the hopeful spirit of Australia after World War II. Many sites have archaeological potential. The Waterous steam engine is a rare and important piece of engineering history. The site can also help us understand how climate change and flooding might affect coastal communities in the future. It can also show the effects of long-term immersion in water on buildings.

Unique and Rare: Uniqueness of the Site

This site is important because it is one of only two similar sites in Australia. The other is nearby Lake Jindabyne. Old Adaminaby and Jindabyne were the only two towns flooded to create dams for the Snowy Scheme. Old Adaminaby is the only one that has been revealed again during drought conditions.

Old Adaminaby was the first and larger town to be flooded. Jindabyne was much smaller. The flooding of the Eucumbene Valley affected more people. Also, Jindabyne did not have as many different old items from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. After the experience with Old Adaminaby, the process of moving Jindabyne's residents was handled differently.

It is very rare and unexpected that Old Adaminaby has reappeared after 50 years. The items that survived being underwater and then exposed are unique. Jindabyne, however, is in deeper water and is unlikely to be seen again.

One item found at Lake Eucumbene, the Waterous boiler, is one of only three complete examples known in the world.

Showing Key Features: Representative Characteristics

The remaining buildings and items of Old Adaminaby and the surrounding areas show features of similar settlements in New South Wales. They represent over a century of development in towns, farms, industries, and transport.

However, in this case, all further development stopped suddenly in the late 1950s. So, the remaining buildings and items of Old Adaminaby are like a time capsule from that period.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |