Operations on the Ancre, January–March 1917 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operations on the Ancre, January–March 1917 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The First World War | |||||||||

The Western Front, 1917 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

British Empire French Empire |

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Robert Nivelle Douglas Haig Hubert Gough Henry Rawlinson |

Erich Ludendorff Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern Max von Gallwitz |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Fourth Army Fifth Army |

1st Army | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 2,151 (incomplete) | 5,284 prisoners | ||||||||

The Operations on the Ancre were a series of battles during the First World War. They took place from 11 January to 13 March 1917. The British Fifth Army fought against the German 1st Army. These battles happened on the Somme front in France.

After the Battle of the Ancre in November 1916, fighting on the Somme stopped for winter. Soldiers faced terrible conditions like rain, snow, fog, and deep mud. Trenches and shell-holes were filled with water. Despite this, the British kept preparing for a big attack, the Battle of Arras, planned for spring 1917.

Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander, told the Fifth Army to attack German defenses. The goal was to keep German troops busy. Small advances would help the British see more of the German positions. This would also threaten the German hold on the village of Serre. Better views meant British artillery could aim more accurately.

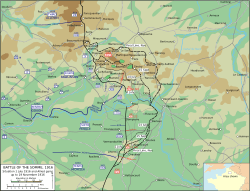

The British also planned a larger attack north of Bapaume. This area had been a bulge in the front line during the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Once the ground dried, they planned to attack from the Ancre valley and from Arras. They hoped to meet at St Léger.

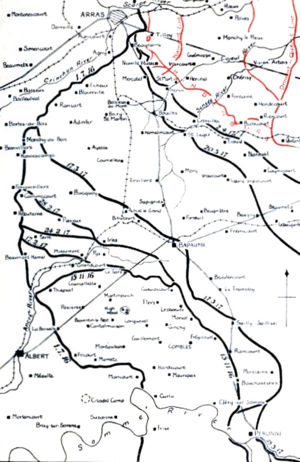

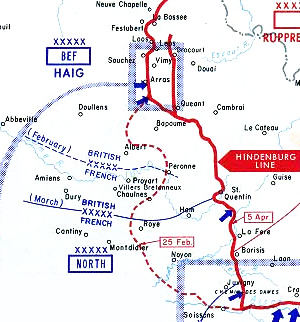

From 11 January to 22 February 1917, British actions pushed the Germans back about 5 miles. This happened on a 4-mile wide front. It forced the Germans to retreat earlier than they had planned. The British captured 5,284 German prisoners. On 22 and 23 February, the Germans pulled back another 3 miles. By 11 March, they had moved even further back. The main German retreat to the Hindenburg Line began on 16 March.

Background to the Battles

German Defenses

By late 1916, German defenses on the south side of the Ancre valley had been pushed back. They used fortified villages and trench networks. Most of these were on slopes hidden from British view. On the north side, the Germans still held the Beaumont-Hamel area. Their original front line ran west of Serre.

The Germans had built new defense lines further back. These were called Riegel I Stellung (Reserve Position I) and Riegel II Stellung (Reserve Position II). These lines had double trenches and barbed wire. A third line, Riegel III Stellung, also existed. The German 1st Army held the front from the Somme River north to Gommecourt. They had many troops ready, including ten divisions in reserve.

British Positions

The British Fifth Army held about 10 miles of the Somme front in January 1917. This stretched from Le Sars to Gommecourt Park. The army was divided into different corps. Some corps were in the front line, while others rested and trained.

The British goal was to advance to the Loupart Wood line. This was the first objective after capturing Beaumont Hamel in late 1916. Bad weather had stopped operations then. Over the winter, the Fifth Army made new plans. They wanted to stop the Germans from retreating to their new defenses, the Hindenburg Line. Air photos and prisoner reports showed a German withdrawal was likely.

The Fifth Army's next big goal was to attack the Bihucourt line. This attack was planned for three days before the Arras offensive. The army would then advance to St Léger to meet the Third Army. This would trap the Germans southwest of Arras.

Preparing for Battle

Life in the Mud: 51st (Highland) Division

The ground on the Somme became very bad in November 1916. Constant rain turned the shell-torn land into deep mud. The Ancre valley was the worst, a muddy wasteland of flooded trenches and shell-holes. Soldiers found it incredibly hard to survive. Moving supplies was difficult, often done at night to avoid German fire.

The 51st (Highland) Division took over a section of the front. They had just fought in the Battle of the Ancre and had little rest. The mud was so deep that horses drowned, and men got stuck up to their waists. Ropes were given out to pull soldiers from the mud. New trenches collapsed as soon as they were dug.

Soldiers suffered from dysentery, trench foot, and frostbite. Morale was very low. Moving around at night was dangerous, as parties often got lost. Sometimes, British and German soldiers stumbled into each other's positions by mistake. Conditions for artillery were as bad as the front line.

After three weeks, the trenches improved a little. A frost hardened the ground, but then a thaw made it even worse. The division got gumboots, but many were lost in the mud. Scottish soldiers wore kilts, which caused problems with their legs. Trousers were issued to help. Food was hard to get to the front, so soldiers used "Tommy cookers" to heat tinned food. Even with these efforts, many soldiers got sick. Battalions were relieved every 48 hours to give men a short rest.

The 2nd Division Takes Over

The 2nd Division replaced the Highlanders on 13 January. They held a 2,500-yard front. The front line had 18 infantry posts. Communication trenches were full of mud and unusable. Both sides were quiet for the rest of January.

Later, a German raid was stopped by machine-gun fire. On the north side of the valley, British troops captured more land. By the end of January, conditions were better. Snowstorms made it hard to see landmarks, and relief parties often got lost. British planes took photos of the front line, giving commanders important information. The ground stayed frozen for about five weeks, making movement easier.

7th Division's Challenges

On the north bank of the Ancre, the 7th Division returned to the front. They had marched 82 miles south in rain and fog. Conditions were even worse than on the south side. Many soldiers got sick despite efforts to prevent trench foot. The temperature dropped, hardening the ground, but then brought heavy rain.

German snipers caused many British casualties. During one trench relief, the mud was so bad that a special rescue team was needed. Many men had to go to the hospital, and one soldier died from exposure. The area was full of damaged and destroyed trenches. It was impossible to tell where the front line was.

Despite the mud, both sides launched raids. On 25 November, about 100 Germans were pushed back. The British extended their trenches, preparing for an attack. German prisoners were taken more often in December and January. Many were deserters.

Raiding continued. On 1 January, British officers met a German attack. A counter-attack failed due to German machine-gun fire. On 5 January, British artillery fired many shells at a German post. Fifty British troops then attacked through the mud. They recaptured the post, taking nine prisoners.

A Daring Trench Raid: 4/5 February

The 2nd Division planned a raid for the night of 4/5 February. A group of 60 men and two officers would attack a German trench. Their goals were to take prisoners, find documents, destroy machine-guns, and learn about German defenses. Stokes mortars would fire, and artillery would create a "box barrage" to trap the Germans.

The raiders wore white suits for camouflage in the snow. They removed anything that could identify them if captured. They practiced the attack for five days and nights. On the night of the raid, they moved forward quietly. Tripods helped them stay on course.

At 3:00 a.m., the Stokes mortars fired. A minute later, the artillery barrage began. The raiders rushed the German position through barbed wire. They quickly captured the trench. After searching dugouts, they withdrew with 51 prisoners, including two officers. They also destroyed a machine-gun. The raiders had one man killed and twelve wounded.

Battles on the Ancre

Early Attacks: 11 January – 14 February

British operations in November 1916 had captured German positions. But the weather stopped further advances. On 10 January, the 7th Division attacked German trenches. The attack followed an 18-hour bombardment. Despite the mud, the infantry advanced. They captured their objectives. A German counter-attack was stopped by British artillery. The 7th Division took 142 prisoners.

The next day, the 7th Division attacked Munich Trench. The attack began at 5:00 a.m. in thick fog. British artillery fired a creeping barrage, moving slowly due to the mud. German resistance was light. The British captured the ground and fortified it.

For the rest of January, British troops dug forward. The cold weather made movement easier, but digging was almost impossible. Small attacks became easier. The British continued to move troops around.

On 2 February, the 32nd Division advanced slightly. The next day, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division tried a surprise attack. They attacked Puisieux and River trenches. Despite moonlight and snow, they captured most of the trenches. A German counter-attack failed. The British suffered 671 casualties but took 176 German prisoners. The Germans abandoned Grandcourt that night.

On 7 February, the 63rd Division captured Baillescourt Farm. On 10 February, the 32nd Division advanced 600 yards, threatening Serre. They captured more of Ten Tree Alley. German counter-attacks failed. Each small British attack succeeded. The captured land gave the British better views of German defenses.

Actions of Miraumont: 17–18 February

The British planned more small advances in the Ancre valley. They aimed to capture several key locations. These attacks would happen three days before the main Arras offensive. Capturing Hill 130 would give them a view over Miraumont and Pys.

British artillery began firing on 14 February. They used new shells that were good at cutting wire. Fog and mist made aiming difficult. At the start of the attack, heavy artillery would bombard German positions. Artillery tactics used a "creeping barrage" that moved slowly in front of the infantry.

On 16 February, a thaw began, turning the ground to deep mud. The creeping barrage was too fast for these conditions. At 4:30 a.m., German artillery fired on the British. The Germans seemed to know about the attack. British soldiers suffered many casualties as they gathered.

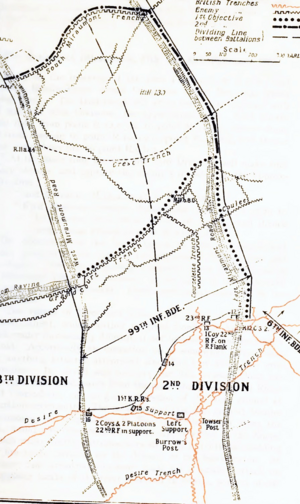

The attack on the right flank failed. This affected other attacks further west. The 99th Brigade attacked a 700-yard front. The 54th Brigade faced a steep slope. Both were vulnerable to German fire. They had three objectives, including Hill 130 and the railway.

The British infantry advanced against light German artillery fire. But the darkness, fog, and mud slowed them down. Units became disorganized. The 99th Brigade reached its first objective. But the 54th Brigade found uncut wire and lost the barrage. Germans emerged from cover and held them up.

The 53rd Brigade captured Grandcourt Trench quickly. But they were stopped at Coffee Trench by more uncut wire. Boom Ravine held out until 7:45 a.m. The advance continued far behind the barrage. On the right, the 99th Brigade struggled with fog and mud. German machine-gun fire caused many casualties.

Some British troops briefly entered South Miraumont Trench but were forced back. German reinforcements counter-attacked. Many British weapons were clogged with mud. The attack advanced the line 500 to 1,000 yards. Boom Ravine was captured, but the Germans held Hill 130. The British suffered 2,207 casualties.

On the north bank, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division attacked. They aimed to capture 700 yards of road to gain a view over Miraumont. The darkness, fog, and mud were bad, but German defense was weaker. The creeping barrage moved slower, which helped. The objective was reached by 6:40 a.m. The 63rd Division had 549 casualties. Overall, the three divisions took 599 prisoners.

The sudden thaw and fog made wire cutting difficult. The Germans seemed to be warned, which helped them defend. From 10 January to 22 February, the Germans were pushed back 5 miles. The Battle of Miraumont forced the Germans to start their retreat from the Ancre valley early. On 24 February, patrols found the Germans had left. By 17 March, British and Australian patrols entered Bapaume.

Operations on the Somme

Smaller Attacks

In January and February, the British Fourth Army began to take over from French troops. Despite these movements, smaller operations continued. The goal was to make the Germans think the Battle of the Somme was restarting. On 27 January, the 29th Division attacked. They took 368 prisoners for 382 casualties.

On 1 February, the 2nd Australian Division attacked Stormy Trench. They took part of it but were forced out by a German counter-attack. They attacked again on 4 February with more artillery and grenades. They pushed back a German counter-attack after a long fight.

On 8 February, the 17th (Northern) Division attacked a trench near Saillisel. They had spent three weeks digging trenches in the frozen ground. The attack succeeded quickly. German counter-attacks failed. British attacks on this front stopped until the end of the month.

The 8th Division planned a detailed attack for 4 March. They had specific instructions for everything. This included communications, supplies, and medical care. They even had rules for officers' clothing and how to signal for help. Morale was low on both sides, so special plans were made for soldiers who got lost or left their units.

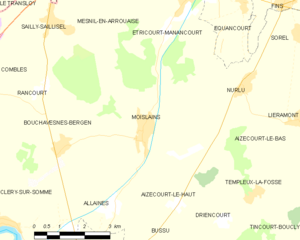

The attack aimed to capture the Malassise Spine. This ridge overlooked Bouchavesnes and the Moislains valley. Capturing it would deny the Germans a good view. It would also threaten German positions near Péronne. The attack involved two brigades. No heavy bombardment was fired on the objectives. But wire cutting and strongpoint bombardments happened for days.

The freezing weather stopped them from digging assembly trenches. Soldiers had to line up in the open. They were given chewing gum to stop coughing. A slight mist and frost helped the attack. The barrage began on time. The first objective, Pallas Trench, was taken with few losses.

The attackers reached the second objective quickly. Some even went beyond it. The Germans in a nearby wood preparing to counter-attack were scattered by machine-gun fire. German troops who were overrun were captured or killed. During the day, the Germans counter-attacked five times but were pushed back. German artillery caused more casualties as the British dug new trenches.

German bombardments continued on the night of 4/5 March. A German counter-attack captured a small part of a trench. But a British attack quickly recovered the lost ground. German bombardments continued on 6 March before slowing down. The operation cost the British 1,137 casualties. They captured 217 German prisoners. This attack, along with the capture of Irles on 10 March, forced the Germans to start their retreat to the Hindenburg Line two weeks early.

Air Operations

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) changed its organization after the Battle of the Somme. During the winter of 1916–1917, these changes worked well. On good flying days, there was a lot of air combat. German planes started patrolling the front line more often.

By January 1917, the RFC had improved. They flew in formations, and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) sent pilots with Sopwith Pup planes. These planes were as good as the best German aircraft. Both sides also started flying at night. British planes continued to fly dangerous missions. They observed German fort building behind the Somme and Arras fronts. On 25 February, reconnaissance crews reported many fires behind the German front line. The next day, 18 Squadron reported how strong the new German line was.

Aftermath of the Operations

German Retreats on the Ancre

British attacks in January 1917 happened against tired German troops. These troops were in poor defensive positions from the 1916 fighting. Some German soldiers had low morale and were willing to surrender. The German commander, Crown Prince Rupprecht, suggested retreating to the Hindenburg Line on 28 January. General Erich Ludendorff refused at first but then agreed on 4 February.

The British attacks in the Actions of Miraumont (17–18 February) made Rupprecht order a retreat on 18 March. The German 1st Army pulled back about 3 miles on a 15-mile front. This retreat surprised the British, even though they had intercepted German radio messages.

The second German retreat happened on 11 March. The British didn't notice until the night of 12 March. Patrols found the line empty between Bapaume and Achiet-le-Petit. A British attack on Bucquoy on the night of 13/14 March failed with many losses. German retreats on the Ancre spread south. On 16 March, the main German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line began. The Germans retreated slowly, using rear-guards and demolishing roads and bridges.

The Alberich Bewegung (Alberich Maneuver)

The severe cold ended in March, and thaws turned the roads into mudslides. German demolitions made it hard to move supplies forward. Many British horses had died from cold and overwork, leaving the Fifth Army short of 14,000 horses.

The 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division and 19th (Western) Division fought their way into Puisieux on 27 February. They began skirmishing towards Bucquoy by 2 March. The 18th (Eastern) Division quickly captured Irles on 10 March.

The 7th and 46th (North Midland) Division were ordered to take Bucquoy on 14 March. Air reconnaissance reported it was almost empty. But British commanders protested, saying the village was well-defended. The V Corps commander insisted on the attack. The artillery bombardment alerted the Germans, who pushed back the attack. The British suffered many casualties. The Germans withdrew two days later.

On 19 March, the I Anzac Corps was ordered to advance. They thought the Germans were retreating beyond the Hindenburg Line. Australian divisions advanced past Bapaume. They captured Beaumetz but lost it to a German counter-attack. The 7th Division commander, after the costly failure at Bucquoy, delayed his advance. The Hindenburg Line was not finished on the Fifth Army front. A quick advance might let the British attack before it became "impregnable."

The village of Croisilles eventually fell on 2 April. This was part of a larger attack on a 10-mile front. It happened after four days of bombardment. Moving over the destroyed ground was very difficult. Roads were rebuilt, and more pack animals were used to carry supplies.

The British command was careful not to risk unsupported forces. They learned that hasty attacks were not practical once the Germans began their main retreat. So, they chose a steady pursuit instead. The determined German defense of outpost villages gave them time to finish the Hindenburg Line. By 8 April, the Fifth Army was far enough forward to help the Third Army attack at Arras. They had captured several outpost villages.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |