Osamu Dazai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Osamu Dazai

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 太宰 治 | |||||

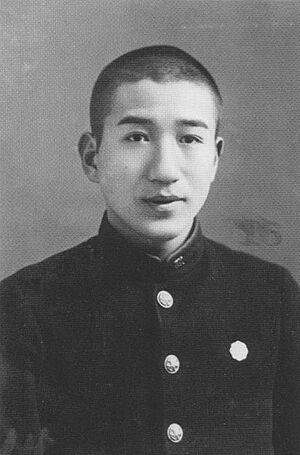

Dazai in 1948

|

|||||

| Born |

Shūji Tsushima

June 19, 1909 Kanagi, Aomori, Empire of Japan

|

||||

| Died | June 13, 1948 (aged 38) Tokyo, Allied-occupied Japan

|

||||

| Occupation | Novelist, Short story writer | ||||

|

Notable work

|

|

||||

| Movement | I-Novel, Buraiha | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 太宰 治 | ||||

| Hiragana | だざい おさむ | ||||

|

|||||

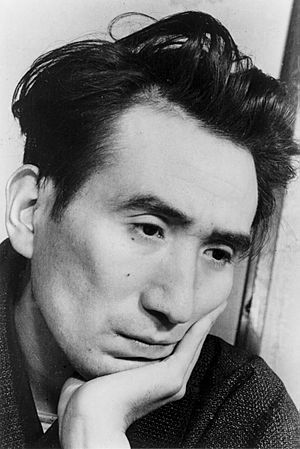

Osamu Dazai (born Tsushima Shūji in 1909; died 1948) was a famous Japanese author. Many of his most popular books, like The Setting Sun and No Longer Human, are considered modern classics.

He was inspired by other great writers such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. While Dazai is very popular in Japan, he is not as well-known in other countries. Only a few of his books are available in English. His last book, No Longer Human, is his most famous work outside of Japan.

Contents

Osamu Dazai's Early Life

Shūji Tsushima, who later became known as Osamu Dazai, was born on June 19, 1909. He was the eighth child in a very wealthy family. His family owned a lot of land in Kanagi, Aomori, a quiet part of northern Japan.

His family's large home, called the Tsushima mansion, was home to about thirty family members. Dazai's family started out as peasants. However, his great-grandfather became rich by lending money. His son then made the family even wealthier. They quickly became very respected in their region.

Dazai's father, Gen'emon, was adopted into the Tsushima family. He married the eldest daughter, Tane. His father became involved in politics because he was one of the four richest landowners in the area. He was often away from home during Dazai's childhood.

Dazai's mother, Tane, was often ill. So, Dazai was mostly raised by the family's servants and his aunt Kiye.

Education and Writing Career

In 1916, Tsushima started school at Kanagi Elementary. His father, Gen'emon, passed away in March 1923. A month later, Tsushima went to Aomori High School.

He then joined Hirosaki University's literature department in 1927. He became interested in Edo culture. He also began studying gidayū, which is a type of chanted story used in puppet theaters. Around 1928, Tsushima helped edit student publications. He also wrote some of his own stories for them.

He even published a magazine called Saibō bungei (Cell Literature) with his friends. Later, he became part of the college's newspaper staff.

Developing as a Writer

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote many detailed novels and short stories. These stories often included parts of his own life.

Japan entered the Pacific War in December 1941. Tsushima was not required to join the army. This was because of his ongoing health issues.

Many stories Dazai published during World War II were new versions of old tales. He retold stories by Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). His works from this time include Udaijin Sanetomo (1943) and Tsugaru (1944). He also wrote Pandora no hako (Pandora's Box, 1945–46).

Another work was Otogizōshi (Fairy Tales, 1945). In this book, he retold old Japanese fairy tales in a very lively and clever way.

Dazai's home was destroyed twice during the American bombing of Tokyo. However, his family was safe. His son, Masaki, was born in 1944. His third child, a daughter named Satoko, was born in May 1947. Satoko later became a famous writer herself, known as Yūko Tsushima.

Post-War Success and Famous Books

After the war, Dazai became very popular. He wrote about the difficult life in Tokyo after the war. One such book was Viyon no Tsuma (Villon's Wife, 1947). This story is about a poet's wife who keeps going despite many hardships.

In 1946, Osamu Dazai released a book called Kuno no Nenkan (Almanac of Pain). This was a personal story about how Dazai felt after Japan lost World War II. It showed the feelings of many Japanese people at that time.

Dazai also wrote Jugonenkan (For Fifteen Years), another story about his own life.

In July 1947, Dazai's most famous book, Shayo (The Setting Sun), was published. This book showed the decline of the Japanese nobility after the war. It made the already popular writer a true celebrity.

Dazai's health got worse quickly. He began writing his novel No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku, 1948) at a hot-spring resort. He finished the novel in Ōmiya. This book is now considered one of the most important books in Japanese literature. It has been translated into many languages.

In the spring of 1948, Dazai was working on a short novel called Guddo bai (Good-Bye). It was meant to be published in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, but he never finished it.

Osamu Dazai's Final Years

Osamu Dazai passed away on June 19, 1948, at the age of 38. His grave is at the Zenrin-ji temple in Mitaka, Tokyo.

Osamu Dazai's Famous Books

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | 思い出 Omoide | Memories | Part of Bannen |

| 1935 | 道化の華 Dōke no Hana | The Flowers of Buffoonery | Part of Bannen |

| 1936 | 虚構の春 Kyokō no Haru | False Spring | Part of Bannen |

| 1936 | 晩年 Bannen | The Late Years | A collection of short stories |

| 1937 | 二十世紀旗手 Nijusseiki Kishu | A Standard-Bearer of the Twentieth Century | |

| 1939 | 富嶽百景 Fugaku Hyakkei | One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji | |

| 女生徒 Joseito | Schoolgirl | ||

| 1940 | 女の決闘 Onna no Kettō | Women's Duel | |

| 駈込み訴へ Kakekomi Uttae | Heed My Plea | ||

| 走れメロス Hashire Merosu | Run, Melos! | ||

| 1941 | 新ハムレット Shin-Hamuretto | New Hamlet | |

| 1942 | 正義と微笑 Seigi to Bisho | Right and Smile | |

| 1943 | 右大臣実朝 Udaijin Sanetomo | Minister of the Right Sanetomo | |

| 1944 | 津軽 Tsugaru | Tsugaru | |

| 1945 | パンドラの匣 Pandora no Hako | Pandora's Box | |

| 新釈諸国噺 Shinshaku Shokoku Banashi | A New Version of Countries' Tales | ||

| 惜別 Sekibetsu | A Farewell with Regret | ||

| お伽草紙 Otogizōshi | Fairy Tales | Collection of short stories | |

| 1946 | 冬の花火 Fuyu no Hanabi | Winter's Firework | A play |

| 苦悩の年鑑 Kuno no Nenkan | Almanac of Pain | An autobiography | |

| 十五年間 Jugonenkan | For Fifteen Years | An autobiography | |

| 1947 | ヴィヨンの妻 Viyon No Tsuma | Villon's Wife | |

| 斜陽 Shayō | The Setting Sun | ||

| 1948 | 如是我聞 Nyozegamon | I Heard It in This Way | An essay |

| 桜桃 Ōtō | A Cherry | ||

| 人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku | No Longer Human | (Also known as A Shameful Life in a 2018 English translation) | |

| グッド・バイ Guddo-bai | Good-Bye | Unfinished |

See also

In Spanish: Osamu Dazai para niños

In Spanish: Osamu Dazai para niños

- Dazai Osamu Prize

- List of Japanese writers

- Osamu Dazai Memorial Museum

Images for kids