Osteoclast facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Osteoclast |

|

|---|---|

|

|

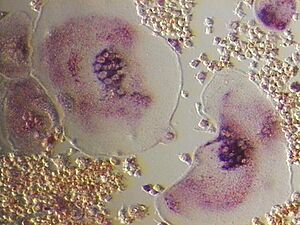

| Close-up view of an osteoclast cell. You can see it's a big cell with many nuclei and a "foamy" inside. | |

|

|

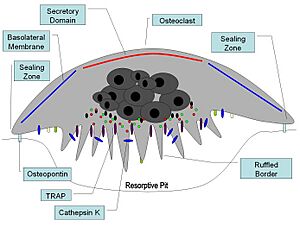

| A drawing that shows one osteoclast. | |

| Latin | osteoclastus |

| Precursor | osteoclast progenitors |

An osteoclast is a special type of bone cell that helps break down bone tissue. This is super important for keeping our bones healthy, repairing them when they get damaged, and reshaping them as we grow. Think of osteoclasts as the "clean-up crew" for your bones. They work by secreting acid and special enzymes to dissolve and digest old or damaged bone. This process is called bone resorption. It also helps control the amount of calcium in your blood, which is vital for many body functions.

Osteoclasts are found on the surfaces of bones where bone is being removed. They often sit in shallow dips called resorption bays or Howship's lacunae, which they create themselves! The bottom part of an osteoclast has many folds, like tiny fingers, called a ruffled border. This border touches the bone surface. Around this ruffled border is a clear area that helps the cell stick tightly to the bone. This creates a sealed-off space where the osteoclast can release its powerful bone-dissolving chemicals.

First, osteoclasts pump out hydrogen ions (which make things acidic) into this space. This acid dissolves the hard minerals in the bone. After the minerals are gone, the osteoclast releases enzymes that break down the remaining organic parts of the bone, like collagen. The osteoclast then "eats" these broken-down pieces. Because they can "eat" things, osteoclasts are part of a group of cells called the mononuclear phagocyte system. Hormones also control how active osteoclasts are. For example, a hormone called calcitonin slows them down.

An odontoclast is like an osteoclast, but it works on the roots of deciduous teeth (your baby teeth) to help them fall out.

Contents

What Osteoclasts Look Like

Osteoclasts are very large cells and have many nuclei (the control centers of the cell). Human osteoclasts usually have about four nuclei and are quite big, around 150–200 micrometers wide. To give you an idea, that's about twice the width of a human hair! Their large size and many nuclei help them focus the work of many smaller cells on one specific area of bone.

Where Osteoclasts Are Found

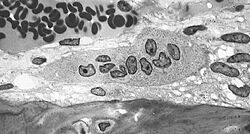

In bones, osteoclasts are located in small pits on the bone surface. These pits are called resorption bays or Howship's lacunae. The inside of an osteoclast often looks "foamy." This is because it's full of small sacs called vesicles and vacuoles. Some of these sacs are lysosomes, which contain special enzymes like acid phosphatase. Scientists can identify osteoclasts by looking for high levels of certain enzymes, like tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP).

When an osteoclast is actively breaking down bone, it forms a special cell membrane called the "ruffled border." This border has many folds, which helps the cell work faster by increasing the surface area for secreting chemicals and taking in dissolved bone parts. This ruffled border is a key sign that an osteoclast is busy at work!

How Osteoclasts Develop

For a long time, scientists debated where osteoclasts came from. Now we know that these cells develop from the fusion (joining together) of smaller cells called macrophages. Imagine many small macrophages coming together to form one big, powerful osteoclast!

For osteoclasts to form, two important signals are needed: RANKL and M-CSF. These signals come from nearby cells, like stromal cells and osteoblasts (which are bone-building cells). These signals tell the macrophages to join up and become osteoclasts.

Another important molecule called osteoprotegerin (OPG) can stop osteoclast formation. OPG is made by osteoblasts and acts like a shield, blocking the RANKL signal. So, osteoblasts (bone builders) can also help control how many osteoclasts (bone removers) are active.

What Osteoclasts Do

When osteoclasts are activated, they move to areas of bone that need to be broken down, often where there are tiny cracks. They settle into the small pits they create, called Howship's lacunae. The osteoclast then forms a tight seal around the area it's working on.

Inside this sealed-off space, the osteoclast releases hydrogen ions. These ions create an acidic environment, which helps dissolve the hard mineral parts of the bone. This process releases calcium and other substances. If the enzyme that helps make these hydrogen ions doesn't work right, it can lead to bone problems.

Besides acid, osteoclasts also release powerful hydrolytic enzymes, like cathepsin K. These enzymes digest the organic parts of the bone, such as collagen. All these chemicals work together to break down the bone matrix.

Odontoclast

An odontoclast is a type of osteoclast that helps with the absorption of the roots of deciduous teeth (baby teeth). This is why baby teeth eventually become loose and fall out!

Other Uses of the Term

The word "osteoclast" can also refer to an old surgical tool used to break and reset bones. To avoid confusion, the cell was first called "osotoclast." But when the surgical tool was no longer used, the cell became known by its current name.

Why Osteoclasts Are Important in Health

Sometimes, osteoclasts can become too large or too active, which can happen in certain bone diseases like Paget's disease of bone. In cats, abnormal osteoclast activity can cause problems with their teeth, leading to feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions.

Osteoclasts also play a big role in how braces work. When you get braces, they gently push your teeth, causing some bone to be broken down by osteoclasts on one side and new bone to be built by osteoblasts on the other side. This allows your teeth to move into their new positions.

History

Osteoclasts were first discovered by a scientist named Kölliker in 1873.

See also

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |