Otranto Barrage facts for kids

The Otranto Barrage was a special naval barrier set up by the Allied forces during World War I. It was located in the Strait of Otranto, a narrow sea passage between Italy (near Brindisi) and Greece (near Corfu). The main goal of this barrier was to stop the Austro-Hungarian Navy from leaving the Adriatic Sea and entering the wider Mediterranean Sea. If they got out, they could attack Allied ships and operations. The barrier worked well at stopping large surface ships. However, it was not very effective against submarines based in places like Cattaro.

Contents

Setting Up the Blockade

The Strait of Otranto is about 72 kilometers (45 miles) wide. To block this wide area, the Allies used many small ships called drifters. Most of these drifters were British. They usually had a small gun and depth charges. Depth charges were bombs that could explode underwater to damage submarines.

When the blockade started in 1915, about 40 drifters were on patrol at any time. They used special steel nets called "indicator nets." These nets were supposed to catch submarines or at least let the surface ships know they were there. Other drifters waited at Brindisi in Italy. Larger ships like destroyers and aircraft also helped support the drifters.

Challenges of the Barrage

The Allies had many other battles going on, like the Gallipoli Campaign. This meant there weren't enough ships and resources for the Otranto Barrage. Because of this, the barrier wasn't very good at stopping German and Austrian U-boats (submarines). Only one Austro-Hungarian submarine, the U-6, was caught by the nets during the entire war.

Many people thought the strait was simply too wide. It was hard to block it completely with nets, mines, or patrols. Submarines kept slipping through easily. This made the Allies look bad, and some called the system "a large sieve."

Later in the war, from 1917 to 1918, more ships joined the blockade. These included ships from the Australian and American navies. The force grew to 35 destroyers, 52 drifters, and over 100 other vessels. Even with more ships, submarines still managed to get through until the war ended. The Allies later started using a "convoy system" where many ships sailed together. This, along with better teamwork, helped reduce the damage caused by the submarines.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy often launched nighttime raids against the Otranto Barrage. They attacked five times in 1915, nine times in 1916, and ten times in 1917. After one raid in December 1916, Allied leaders decided the drifters needed better protection.

The Great Otranto Raid

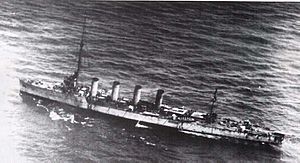

The biggest raid happened on the night of May 14-15, 1917. Three Austro-Hungarian cruisers—SMS Novara, Helgoland, and Saida—led the attack. They were supported by destroyers and submarines. The fleet was commanded by Miklós Horthy, a brave Austro-Hungarian naval officer.

During this raid, Horthy's fleet sank 14 drifters out of 47 on duty. They also badly damaged three more. One hero, Skipper Joseph Watt, was later given the Victoria Cross for bravely defending his drifter, Gowanlea, against heavy attack from the Novara.

Allied ships from Brindisi quickly responded. British light cruisers HMS Dartmouth and Bristol, along with Italian and French destroyers, sailed out to fight the Austrians. This led to the Battle of the Otranto Straits. The British ships damaged the Saida and disabled the Novara, badly injuring Horthy. However, the British ships stopped fighting when they heard that more strong Austrian forces were coming from Cattaro. The Saida then towed the damaged Novara back to port.

As the British cruiser Dartmouth returned to Brindisi, it was damaged by an enemy submarine, the UC-25. The night before, this same submarine had placed mines at the entrance of Brindisi harbor. A French destroyer, the French destroyer Boutefeu, hit one of these mines while leaving the harbor that very day. It exploded and sank with everyone on board.

Last Major Attack

In June 1918, Miklós Horthy, who was now the commander of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, planned another big attack. He wanted to use four of their most modern battleships, the Tegetthoff-class battleships, based at Pola. But as they were sailing down the Adriatic, one of the battleships, the SMS Szent István, was hit by a torpedo from an Italian torpedo boat on June 10. The battleship sank, and because of this, the entire attack was called off.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |