Otto Neurath facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Otto Neurath

|

|

|---|---|

Photo of Neurath published in 1919

|

|

| Born |

Otto Karl Wilhelm Neurath

10 December 1882 |

| Died | 22 December 1945 (aged 63) Oxford, England

|

| Education | University of Vienna (no degree) University of Berlin (PhD, 1906) Heidelberg University (Dr. phil. hab., 1917) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy Logical positivism Vienna Circle Epistemic coherentism |

| Theses |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Gustav Schmoller, Eduard Meyer |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophy of science |

|

Notable ideas

|

Physicalism Protokollsatz (protocol statement) Neurath's boat Isotype |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Otto Karl Wilhelm Neurath (10 December 1882 – 22 December 1945) was an Austrian thinker. He studied how science works, how societies are organized, and how economies function. He also created the ISOTYPE method, which uses pictures to show information. He was also very good at creating new ways to set up museums. Before he left Austria in 1934, Neurath was a key member of the Vienna Circle, a famous group of philosophers.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Otto Neurath was born in Vienna, Austria. His father, Wilhelm Neurath, was a well-known economist. Otto studied math and physics at the University of Vienna. In 1906, he earned his PhD from the University of Berlin. His PhD paper was about trade, business, and farming in ancient times.

In 1907, he married Anna Schapire. She passed away in 1911 while giving birth to their son, Paul. Later, he married Olga Hahn, who was a mathematician and philosopher. Because of the war and his wife's blindness, Paul lived in a children's home for a while. He returned home when he was nine years old.

Working in Vienna

Neurath taught economics in Vienna until World War I began. During the war, he managed the Department of War Economy. In 1917, he finished his advanced degree at Heidelberg University. This paper was about how war economies work and their future importance. In 1918, he became the director of the German Museum of War Economy in Leipzig.

After the war, Neurath joined the German Social Democratic Party. He worked on plans for economic organization in Munich. When a new government took over, he was put in prison. However, the Austrian government helped him return to Austria. While in prison, he wrote a book called Anti-Spengler. It was a strong criticism of another famous book, The Decline of the West.

In Red Vienna, a period when Vienna was led by social democrats, he joined the Social Democrats. He helped groups that aimed to provide housing and gardens for people. In 1923, he started a new museum about housing and city planning. In 1925, he renamed it the Museum of Society and Economy in Vienna. The city government and workers' groups supported this museum.

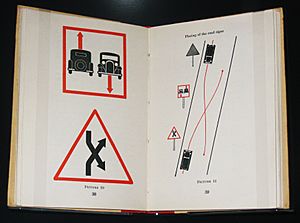

To make the museum easy to understand for everyone, Neurath focused on graphic design. He believed that "Words divide, pictures unite." This was his own saying, which he put on his office wall. In the late 1920s, he worked with illustrator Gerd Arntz and Marie Reidemeister. Together, they created new ways to show information using simple pictures. This was the start of Infographics. He first called it the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics. Later, he called it "Isotype". This name stood for "International System of Typographic Picture Education." Neurath promoted Isotype as a way to communicate ideas using pictures. He also saw it as a tool for adult education.

In the 1920s, Neurath also became a strong supporter of logical positivism. He helped write the main ideas for the Vienna Circle. He was also a key person in the "Unity of Science" movement. This movement aimed to connect all scientific knowledge.

Life in Exile

During the Austrian Civil War in 1934, Neurath was working in Moscow. He had a plan to get a secret message if it was too dangerous to go back to Austria. When he got the message, he went to The Hague, in the Netherlands, instead of Vienna. This allowed him to continue his international work. His wife also moved to the Netherlands, where she passed away in 1937.

After the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam, Neurath and Marie Reidemeister escaped to Britain. They crossed the English Channel in an open boat with other refugees. He and Marie married in 1941. Before that, they were held for a short time on the Isle of Man. In Britain, he and his wife started the Isotype Institute in Oxford. He also helped design Isotype charts for rebuilding areas in England.

Neurath died suddenly in December 1945 from a stroke. After his death, Marie Neurath continued his work at the Isotype Institute. She published his writings and finished projects he had started. She also wrote many children's books using the Isotype system until she passed away in the 1980s.

Key Ideas

Philosophy of Science

Neurath worked on what he called "protocol statements." These are basic reports of experiences. He believed that these reports should be public and impersonal, not just someone's private thoughts. This was important for making scientific knowledge clear to everyone.

One of Neurath's important ideas was called Physicalism. This idea changed how logical positivists thought about connecting all the sciences. Neurath agreed that science should aim to create a universal system of knowledge. He also agreed that ideas that cannot be tested by science (called metaphysics) should be rejected.

However, Neurath disagreed with some ideas about language. He didn't think that language perfectly mirrors reality. Instead, he suggested that reality is simply all the true sentences we have. The "truth" of a new sentence depends on how well it fits with all the sentences we already accept as true. If a new sentence doesn't fit, then either it's false, or some of our old ideas need to change. This means that truth is about how ideas fit together, not just about facts in the world.

Neurath also believed that science should not be based on personal feelings or experiences. He thought that these are too subjective. Instead, he argued that science should use the language of math and physics. This language is more objective because it describes things using space and time. This "physicalistic" approach helps remove any ideas that cannot be scientifically tested.

Neurath also said that language itself is a physical system. Because it's made of sounds or symbols, it can describe its own structure. These ideas helped form the basis of physicalism, which is still a major idea in philosophy today.

Economics

In economics, Neurath was known for supporting "in-kind" accounting instead of using money. This means tracking goods and services directly, rather than their money value. In the 1920s, he also pushed for "complete socialization." This meant making the economy much more controlled by society than what mainstream political parties wanted.

Neurath debated these ideas with other economists. He had seen during the war that goods like ammunition and food were managed directly, not just with money. This made him believe that economic planning could work by tracking amounts of goods and services, without needing money.

Otto Neurath thought that "war socialism" would come after capitalism. He saw that war economies could make decisions and act quickly. They could also use resources well to meet military goals. He believed that scientific methods could be used to improve how work is done.

Neurath's view on how societies develop was similar to classical Marxism. He thought that technology and new ways of thinking would clash with old social structures. He believed that scientific thinking and empiricism (ideas based on experience) were linked to the rise of socialism. These new ways of thinking were challenging older ideas like theology, which he saw as supporting old ways of power.

Selected Publications

Many of Neurath's writings are in German. However, he also wrote in English, using a simplified English called Basic English. His scientific papers are kept in Haarlem, Netherlands. The Otto and Marie Neurath Isotype Collection is at the University of Reading in England.

Books

- 1913. Serbiens Erfolge im Balkankriege: Eine wirtschaftliche und soziale Studie. Wien : Manz.

- 1921. Anti-Spengler. München, Callwey Verlag.

- 1926. Antike Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Leipzig, Berlin: B. G. Teubner.

- 1928. Lebensgestaltung und Klassenkampf. Berlin: E. Laub.

- 1933. Einheitswissenschaft und Psychologie. Wien.

- 1936. International Picture Language; the First Rules of Isotype. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co., ltd., 1936

- 1937. Basic by Isotype. London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co., ltd.

- 1939. Modern Man in the Making. Alfred A. Knopf

- 1944. Foundations of the Social Sciences. University of Chicago Press

- 1944. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. With Rudolf Carnap, and Charles W. Morris (eds.). University of Chicago Press.

- 1946. Philosophical Papers, 1913–1946: With a Bibliography of Neurath in English. Marie Neurath and Robert S. Cohen, with Carolyn R. Fawcett, eds. 1983

- 1973. Empiricism and Sociology. Marie Neurath and Robert Cohen, eds. With a selection of biographical and autobiographical sketches by Popper and Carnap. Includes abridged translation of Anti-Spengler.

Articles

- 1912. The problem of the pleasure maximum. In: Cohen and Neurath (eds.) 1983

- 1913. The lost wanderers of Descartes and the auxiliary motive. In: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1916. On the classification of systems of hypotheses. In: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1919. Through war economy to economy in kind. In: Neurath 1973 (a short fragment only)

- 1920a. Total socialisation. In: Cohen and Uebel 2004

- 1920b. A system of socialisation. In: Cohen and Uebel 2004

- 1928. Personal life and class struggle. In: Neurath 1973

- 1930. Ways of the scientific world-conception. In: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1931a. The current growth in global productive capacity. In: Cohen and Uebel 2004

- 1931b. Empirical sociology. In: Neurath 1973

- 1931c. Physikalismus. In: Scientia : rivista internazionale di sintesi scientifica, 50, 1931, pp. 297–303

- 1932. Protokollsätze (Protocol statements).In: Erkenntnis, Vol. 3. Repr.: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1935a. Pseudorationalism of falsification. In: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1935b. The unity of science as a task. In: Cohen and Neurath 1983

- 1937. Die neue enzyklopaedie des wissenschaftlichen empirismus. In: Scientia: rivista internazionale di sintesi scientifica, 62, 1937, pp. 309–320

- 1938 'The Departmentalization of Unified Science', Erkenntnis VII, pp. 240–46

- 1940. Argumentation and action. The Otto Neurath Nachlass in Haarlem 198 K.41

- 1941. The danger of careless terminology. In: The New Era 22: 145–50

- 1942. International planning for freedom. In: Neurath 1973

- 1943. Planning or managerial revolution. (Review of J. Burnham, The Managerial Revolution). The New Commonwealth 148–54

- 1943–5. Neurath–Carnap correspondence, 1943–1945. The Otto Neurath Nachlass in Haarlem, 223

- 1944b. Ways of life in a world community. The London Quarterly of World Affairs, 29–32

- 1945a. Physicalism, planning and the social sciences: bricks prepared for a discussion v. Hayek. 26 July 1945. The Otto Neurath Nachlass in Haarlem 202 K.56

- 1945b. Neurath–Hayek correspondence, 1945. The Otto Neurath Nachlass in Haarlem 243

- 1945c. Alternatives to market competition. (Review of F. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom). The London Quarterly of World Affairs 121–2

- 1946a. The orchestration of the sciences by the encyclopedism of logical empiricism. In: Cohen and. Neurath 1983

- 1946b. After six years. In: Synthese 5:77–82

- 1946c. The orchestration of the sciences by the encyclopedism of logical empiricism. In: Cohen and. Neurath 1983

- 1946. From Hieroglyphics to Isotypes. Nicholson and Watson. Excerpts. Rotha (1946) claims that this is in part Neurath's autobiography.

See also

In Spanish: Otto Neurath para niños