Paris–Roubaix facts for kids

|

|

| Race details | |

|---|---|

| Date | Early April |

| Region | Northern France |

| English name | Paris–Roubaix |

| Local name(s) | Paris–Roubaix |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Discipline | Road |

| Competition | UCI World Tour |

| Type | One-day |

| Organiser | Amaury Sport Organisation |

| Race director | Jean-François Pescheux |

| History | |

| First edition | 1896 |

| Editions | 122 (as of 2025) |

| First winner | |

| Most wins | (4 wins each) |

| Most recent | |

Paris–Roubaix is a famous one-day professional bicycle road race held in northern France. It starts near Paris and finishes in the town of Roubaix, close to the border with Belgium. As one of cycling's oldest races, it is considered a "Monument" of the sport. This means it is one of the five most important classic races on the European calendar.

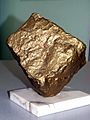

The race is known for its very difficult and bumpy cobblestone roads, also called pavé. Because of these rough roads, it has earned nicknames like The Hell of the North and Queen of the Classics. The winner of the race even gets a real cobblestone as a trophy.

The tough course often causes flat tires and other bike problems, which can change the race's outcome. The race has been held almost every year since it began in 1896, only stopping for the World Wars and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Contents

History of the Race

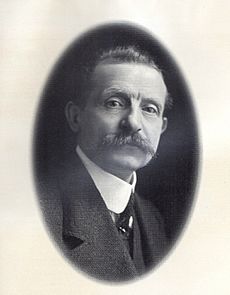

Paris–Roubaix was created in 1896 by two businessmen from Roubaix, Théodore Vienne and Maurice Perez. They had recently built a new cycling track, called a velodrome, and wanted a big race to finish there. They decided to create a race from Paris to their new track in Roubaix.

They asked the editor of a sports newspaper, Le Vélo, for help. The newspaper sent a reporter named Victor Breyer to check the route. Breyer rode the course on his bike and found it incredibly difficult. The roads were muddy, cobbled, and hard to ride on. At first, he wanted to cancel the race, but after talking with the organizers in Roubaix, he changed his mind.

The First Race

The first Paris–Roubaix took place on April 19, 1896. Many riders who signed up didn't even start the race because they heard how tough the course was. One of the local favorites was Maurice Garin, who later became the first winner of the Tour de France.

Garin finished in third place. The winner was Josef Fischer from Germany. Only four riders finished within an hour of Fischer, showing just how hard the race was. Garin won the race the next two years, in 1897 and 1898.

The Hell of the North

The nickname "Hell of the North" came after World War I. In 1919, organizers and reporters drove along the race route to see if it was still usable. The war had destroyed much of northern France.

They saw a landscape full of shell holes, mud, and ruined buildings. The roads were in terrible condition. A journalist described the scene as "hell." The name stuck, and Paris–Roubaix has been called the "Hell of the North" ever since.

The Famous Cobblestones

The cobblestones, or pavé, are the most famous part of Paris–Roubaix. In the past, many roads in France were made of cobblestones. Over time, most were paved over with smooth asphalt. This made the race easier and changed its character.

To keep the race challenging, organizers began searching for old, forgotten cobblestone paths. A group of fans called Les Amis de Paris–Roubaix (The Friends of Paris–Roubaix) was formed in 1983. This group works to protect and repair the old cobblestone roads. Thanks to them, the race still has its famous difficult sections.

The Race Course

The race is about 260 kilometers long. While it used to start in Paris, it now begins in the town of Compiègne. The first 100 kilometers are on normal roads. After that, the riders hit the first of many cobbled sections.

The race includes over 50 kilometers of cobblestones in total. These sections are graded by difficulty, with the hardest ones being the most important. The race ends with one and a half laps around the Roubaix Velodrome.

Key Cobbled Sections

Some parts of the course are so famous they have their own names. These sections are often where the race is won or lost.

Trouée d'Arenberg

The Trouée d'Arenberg (Trench of Arenberg) is a 2.4-kilometer straight road through a forest. The cobblestones here are very old, uneven, and often slippery. It is one of the most dangerous parts of the race. A former cyclist named Jean Stablinski, who used to work in a mine under the forest, suggested adding this road to the race in 1968.

Mons-en-Pévèle

This is another very difficult 3-kilometer section. It has sharp turns and rough cobblestones, making it a tough challenge for tired riders.

Carrefour de l'Arbre

The Carrefour de l'Arbre is one of the last major hurdles. This 2.1-kilometer stretch of rough cobbles comes just 15 kilometers from the finish line. Many decisive moves are made here as riders try to break away before reaching the velodrome.

The Finish Line

The race finishes inside the famous outdoor velodrome in Roubaix. After hundreds of kilometers on brutal roads, the riders enter the stadium for the final sprint on a smooth track.

Inside the velodrome, there is a special shower room for the riders. Each shower stall has a plaque with the name of a past winner. It is a place of honor for those who have conquered the "Hell of the North."

Bikes and Equipment

Paris–Roubaix is so tough that teams use special bikes. These bikes are built to handle the bumpy cobblestones. They often have stronger frames, wider tires, and sometimes even special suspension systems to absorb the shocks.

Punctures are very common, so teams place mechanics along the route with spare wheels and bikes. There is also a neutral service team from the company Mavic that helps any rider who has a problem, no matter what team they are on.

Famous Winners

Two riders hold the record for the most wins at Paris–Roubaix. Roger De Vlaeminck and Tom Boonen, both from Belgium, have each won the race four times.

Other famous three-time winners include Eddy Merckx of Belgium, Francesco Moser of Italy, and Fabian Cancellara of Switzerland.

| Rider | Year |

|---|---|

| 1923 | |

| 1932 | |

| 1934 | |

| 1954 | |

| 1957 | |

| 1962 | |

| 1977 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2005 | |

| 2010 | |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2024 |

Related Races

Since 2021, a women's race called Paris–Roubaix Femmes has been held on the Saturday before the men's race. It follows the same tough terrain but over a shorter distance.

There is also a race for younger riders under 23, called Paris–Roubaix Espoirs. Every two years, amateur cyclists can also ride the course in an event called the Paris–Roubaix Cyclo.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: París-Roubaix para niños

In Spanish: París-Roubaix para niños