Paul Otlet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Otlet

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 August 1868 |

| Died | 10 December 1944 (aged 76) Brussels, Belgium

|

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | One of several people who have been considered the founders of information science |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Information science |

| Institutions | Institut International de Bibliographie (now the International Federation for Information and Documentation) |

| Influences | Henri La Fontaine, Edmond Picard, Melvil Dewey |

| Influenced | Andries van Dam, Suzanne Briet, Douglas Engelbart, J.C.R. Licklider, Ted Nelson, Tim Berners-Lee, Vannevar Bush, Michael Buckland, Robert M. Hayes, Luciano Floridi, Frederick Kilgour, Alexander Ivanovich Mikhailov, S. R. Ranganathan, Gerald Salton, Jesse Shera, Warren Weaver |

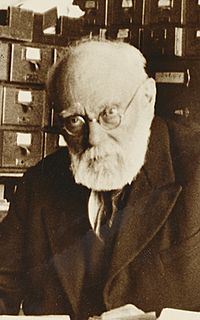

Paul Marie Ghislain Otlet (born August 23, 1868 – died December 10, 1944) was a Belgian writer, lawyer, and peace activist. Many people consider him one of the founders of information science. This field is all about how we collect, organize, and find information. Otlet called his work "documentation."

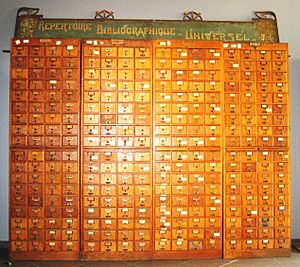

He created the Universal Decimal Classification, a system for organizing knowledge. He also helped develop an early way to find information called the "Repertoire Bibliographique Universel" (Universal Bibliographic Repertory). This system used small index cards, like those once common in libraries. Otlet wrote many essays and books about how to gather and arrange all the world's knowledge.

In 1907, Otlet and his friend Henri La Fontaine started the Central Office of International Associations. It later became the Union of International Associations and is still in Brussels. They also created a huge international center. It was first called Palais Mondial (World Palace), then later the Mundaneum. This center was meant to hold all their collections and activities.

Otlet and La Fontaine were strong supporters of peace. They believed in international cooperation, like the ideas behind the League of Nations. They saw a huge increase in information and wanted to help organize it globally. La Fontaine even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1913 for his efforts.

Contents

- Paul Otlet's Early Life

- How Paul Otlet Became an Information Expert

- The Universal Bibliographic Repertory

- The Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

- Challenges and World War I

- The Mundaneum: A World of Knowledge

- The World City Project

- Exploring New Ways to Share Information

- Paul Otlet's Beliefs

- Later Years and Legacy

- Grave

- Documentary Films About Paul Otlet

- Web Pages About Paul Otlet

- Images for kids

- See also

Paul Otlet's Early Life

Paul Otlet was born in Brussels, Belgium, on August 23, 1868. He was the oldest child of Édouard Otlet and Maria Van Mons. His father, Édouard, was a rich businessman who sold trams around the world. Paul's mother died when he was only three years old.

His father believed classrooms were too strict. So, Paul was taught by tutors at home until he was 11. He didn't have many friends as a child. He mostly played with his younger brother, Maurice. Paul soon grew to love reading and books.

When he was six, his family moved to Paris for a short time. At age 11, Paul went to school for the first time. It was a Jesuit school in Paris. After three years, the family returned to Brussels. Paul then studied at the well-known Collège Saint-Michel. His father later became a senator in the Belgian Senate.

Paul Otlet studied at the Catholic University of Leuven. He also attended the Université Libre de Bruxelles. He earned a law degree in 1890. Soon after, he married Fernande Gloner. He then worked with a famous lawyer named Edmond Picard.

How Paul Otlet Became an Information Expert

Paul Otlet soon found that he didn't enjoy being a lawyer. He became very interested in bibliography, which is the study of books and how they are listed. In 1892, he wrote an essay called "Something about bibliography."

In this essay, he said that books were not the best way to store information. He thought it was hard to find specific facts in them. He believed a better system would use cards. Each card would hold a small piece of information. This would make it easy to sort and find facts. He also thought a detailed map of all knowledge was needed to classify these facts.

In 1891, Otlet met Henri La Fontaine. He was also a lawyer who shared Otlet's interests. They became good friends. In 1895, they found the Dewey Decimal Classification. This system was invented in 1876 for libraries.

Otlet and La Fontaine wanted to make this system even bigger. They wanted it to classify individual facts, not just books. They asked the system's creator, Melvil Dewey, for permission. He agreed, as long as their new system was not translated into English. They started working on it and created the Universal Decimal Classification.

In 1895, Otlet founded the Institut International de Bibliographie (IIB). This organization was later renamed the International Federation for Information and Documentation (FID).

The Universal Bibliographic Repertory

In 1895, Otlet and La Fontaine began collecting index cards. These cards were meant to catalog facts. This collection became known as the "Repertoire Bibliographique Universel" (RBU). It means "Universal Bibliographic Repertory." By the end of 1895, it had 400,000 entries. Later, it grew to more than 15 million entries!

In 1896, Otlet started a service where people could ask questions by mail. He would send them copies of the right index cards. One expert called this service an "analog search engine." By 1912, this service answered over 1,500 questions each year.

Otlet dreamed of having a copy of the RBU in every major city. Brussels would keep the main copy. They tried to send copies to cities like Paris and Washington, D.C. But it was hard to copy and move so many cards.

The Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

In 1904, Otlet and La Fontaine started publishing their classification system. They called it the Universal Decimal Classification. The UDC was based on Melvil Dewey's system. They worked with many experts to expand it. The first part was finished in 1907.

The UDC not only sorts subjects in detail. It also has a way to link different subjects together. For example, a code could refer to the statistics of mining and metal work in Sweden. The UDC is still used by many libraries and information services today. It is even used by the BBC Archives.

Challenges and World War I

In 1906, Paul's father, Édouard, was very ill. His businesses, which included mines and railways, were in trouble. Paul and his siblings formed a company to try and manage them. Paul became the president, even though he was busy with his information work. His father died in 1907.

Paul Otlet also faced personal difficulties. He divorced his first wife and remarried in 1912.

In 1913, Henri La Fontaine won the Nobel Peace Prize. He used his prize money to help fund their information projects. These projects were struggling to find money. In 1914, Otlet went to the United States to try and get more funding. But his efforts stopped when World War I began.

Otlet returned to Belgium, but he had to flee when the Germans took over. He spent most of the war in Paris and Switzerland. Both of his sons fought in the Belgian army. Sadly, one of them, Jean, died during the war.

During the war, Otlet worked hard for peace. He wanted to create international groups that could prevent future wars. In 1914, he published a book called "La Fin de la Guerre" ("The End of War"). It suggested a "World Charter of Human Rights" to build an international federation.

The Mundaneum: A World of Knowledge

In 1910, Otlet and La Fontaine first imagined a "city of knowledge." Otlet called it the "Palais Mondial" ("World Palace"). It was meant to be a central place for all the world's information. After World War I, in 1919, they convinced the Belgian government to support this project. They argued it would help Belgium become the home of the League of Nations.

They were given space in a government building in Brussels. They hired people to help add to their Universal Bibliographic Repertory. In 1924, Otlet renamed the Palais Mondial to the Mundaneum.

The RBU grew steadily. By 1927, it had 13 million index cards. By 1934, it reached over 15 million cards! These cards were stored in special cabinets. They were organized using the Universal Decimal Classification. The Mundaneum also collected files, like letters and newspaper articles, and millions of images.

In 1934, the Belgian government stopped funding the project. The offices were closed. The collection stayed there until 1940. That's when Germany invaded Belgium. The Germans took over the Mundaneum's space. They destroyed many of its collections. Otlet and his team had to find a new home for the Mundaneum. They moved it to another building, where it stayed until 1972.

The World City Project

The World City, or Cité Mondiale, was Paul Otlet's idea for a perfect city. He imagined a city that would bring together all the world's most important organizations. This city would share knowledge with the world. It would also help build peace and cooperation among nations.

Otlet worked with several architects to design this World City. They created many plans. These plans included a World Museum, a World University, a World Library, and offices for international groups. It also had areas for nations, an Olympic Center, homes, and a park.

Paul Otlet always looked for new ways to share knowledge. He wanted to use new technologies as they were invented. In the early 1900s, he worked on storing information on microfilm. This is a way to store tiny images of documents.

These experiments continued into the 1920s. He even tried to create an encyclopedia printed entirely on microfilm. It was called the Encyclopaedia Microphotica Mundaneum.

In the 1920s and 1930s, he wrote about how radio and television could share information. In his 1934 book, Traité de documentation, he wrote that "marvellous inventions have immensely extended the possibilities of documentation." He even predicted future media that could share feel, taste, and smell. He believed an ideal information system should handle all "sense-perception documents."

Paul Otlet's Beliefs

Otlet strongly believed in international cooperation. He thought it would help spread knowledge and bring peace. He considered himself a liberal, a universalist, and a pacifist. His work to organize knowledge showed his belief in structuring information for everyone. The Universal Decimal Classification is a good example of this.

The Union of International Associations, which he co-founded, helped develop the League of Nations. It also contributed to the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, which later became UNESCO.

Otlet also held some views that are now considered outdated and harmful. For example, in some of his writings, he expressed ideas about different groups of people that were based on false beliefs about superiority. It's important to remember that while he had groundbreaking ideas about organizing information, some of his social views were not aligned with modern values of equality.

In 1933, Otlet suggested building a "gigantic neutral World City" in Belgium. He hoped this project would create many jobs and help with the unemployment caused by the Great Depression.

Later Years and Legacy

Paul Otlet died in 1944, near the end of World War II. His main project, the Mundaneum, had been closed. He had also lost all his funding.

After World War I, Otlet's ideas became less popular. He lost support from the Belgian government. His projects, like the Mundaneum, seemed too grand to some.

After World War II, Otlet's contributions to information science were largely forgotten. New ideas from American scientists became more popular.

However, in the 1980s, people started to rediscover Otlet's work. This was especially true after the World Wide Web began in the 1990s. People became interested in his ideas about organizing knowledge and using technology. His 1934 book, Traité de documentation, was reprinted in 1989.

In 1985, a Belgian academic named André Canonne suggested bringing the Mundaneum back. He wanted it to be an archive and museum. With help from others, a new Mundaneum opened in Mons, Belgium, in 1998. This museum is still open today. It holds Otlet's personal papers and the archives of the organizations he created.

Grave

Paul Otlet's grave is in the Etterbeek Cemetery. It is located in Wezembeek-Oppem, Belgium.

Documentary Films About Paul Otlet

- Levie, Françoise, The Man Who Wanted to Classify the World, DVD, 60 minutes, Memento Production, 2006.

- Wright, Alex, The Web That Wasn't: Forgotten Forebears of the Internet, UX Brighton, 2012.

- Snelting, Femke, Fathers of the Internet, Verbindingen/Jonctions 14 – "Are You Being Served?”, December 2013.

- Rayward, Warden Boyd, Biography of Paul Otlet (YouTube, 23:20)

Web Pages About Paul Otlet

- Buckland, Michael, Paul Otlet, Pioneer of Information Management.

- Rayward, Warden Boyd, Bibliography of the works of Paul Otlet.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Paul Otlet para niños

In Spanish: Paul Otlet para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |