Pedro Ciruelo facts for kids

Pedro Sánchez Ciruelo (born around 1465 – died 1548) was a Spanish thinker. He was a philosopher, a religious scholar (theologian), a mathematician, and an expert in stars and planets (astronomer and astrologer). He also wrote about how the natural world works.

Contents

Early Life

Ciruelo was born in Daroca, Spain, sometime between 1460 and 1470. Daroca was an important city in the Kingdom of Aragon. His family had Jewish roots. During the Spanish Inquisition, a time when people with Jewish backgrounds faced challenges in Spain, his family history was looked into. Ciruelo may have said he was an orphan to create distance from his Jewish heritage. This was because his grandfather had been accused of changing his religious beliefs, and an uncle had admitted to returning to Jewish beliefs after becoming Catholic. His family was not thought to be rich; many of them worked in common jobs like shoemaking.

Education and Career

Ciruelo first studied grammar and public speaking (rhetoric) in Daroca. This sparked his love for learning. In 1482, he went to the University of Salamanca, where he became very interested in logic and mathematics. While there, he also developed a strong interest in astronomy and astrology, especially after reading the works of Abraham Zacuto. Ciruelo later mentioned Zacuto and Rodrigo Vasurto, a professor of astrology at Salamanca, in his own writings.

After Salamanca, Ciruelo studied theology at the University of Paris for ten years. There, he joined a group of Spanish scholars called calculatores who were interested in mathematical physics. With Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Ciruelo helped to improve the math lessons at the university. He also published several books with a French printer named Guy Marchant.

In 1502, Ciruelo returned to Spain. He taught philosophy in Sigüenza and later at the University of Zaragoza. In 1509, he moved to the University of Alcalá to teach theology and mathematics. One of his students there was Domingo de Soto. Later, in 1533, he worked at the Segovia Cathedral until 1537. He then moved back to Salamanca, where he continued to write until he passed away.

Works and Beliefs

Ciruelo wrote explanations (commentaries) on important books like the Sphaera de Sacrobosco. He also wrote about Thomas Bradwardine's math books, Arithmetica Speculativa and Geometria Speculativa. These commentaries, along with those from other calculatores, became popular textbooks in many European universities. This helped Paris become a center for math books in the 1400s.

Mathematics Program

Ciruelo and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples played a big role in expanding math teaching at the University of Paris in the late 1400s. At that time, there wasn't a set math plan for students. Ciruelo had his own advanced math program that used five different texts on "theoretical arithmetic, practical arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy."

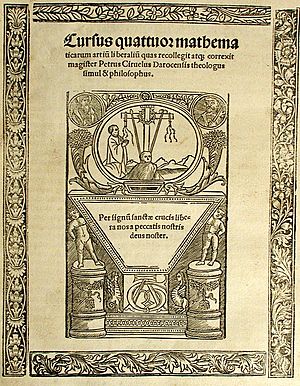

During his time in Paris, Ciruelo wrote four math books. Two were new versions of Thomas Bradwardine's texts, one was an original book, and one was a commentary on Sacrobosco's Sphaera. Ciruelo's books were published by Guy Marchant, who liked Ciruelo's academic background. Printing these math books was sometimes hard because it needed special equipment for figures and numbers.

Ciruelo's Cursus

In his book Cursus quattuor mathematicarum artium liberalium, Ciruelo looked at why we use words like "arithmetical" and "geometrical" to describe number patterns (progressions, sequences, and proportions). He was one of the few people to discuss this history.

You might think these terms come from the math subjects they are used in. But Ciruelo thought differently. He believed the terms showed how these math ideas were used to measure things. This idea is supported by how Aristotle used "geometrical proportion" to talk about measurements in math ratios.

Ciruelo's Cursus also included writings on music theory. These writings showed a shift in 16th-century math, where people started to prove geometry ideas using algebra instead of just drawings. This meant treating geometric shapes as abstract symbols. This was important for music theory, which involves dividing strings into musical intervals. Ciruelo's work could explain these ideas using only numbers, without needing to refer to physical strings. For example, he showed how to break down compound intervals into smaller ones using just numeric ratios. This way of thinking helped lead to "equal temperament" tuning in music.

Ciruelo on Astrology

Ciruelo's main book on astrology, Apotelesmata astrologiae Christianae, came out in 1521. In it, he argued that only people who understood both religion and astrology, like himself, could truly judge the subject. Ciruelo believed that studying the cosmos (the universe) was a way to admire God's creation.

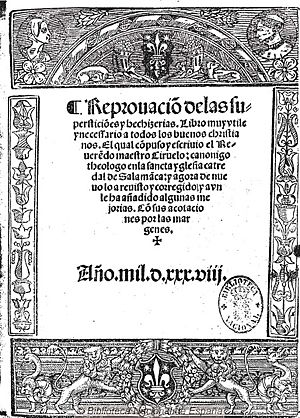

However, he was against certain beliefs. In his 1538 book Reprobación de supersticiones y hechizerías, he set rules for what kinds of astrology were real and which were just superstitions. He said that believing in the evil eye, predicting the future from dreams, using good luck charms (amulets), horoscopes, and making rain were wrong. But he thought that witches flying was real. For him, any practice that claimed to change future events was not right. Ciruelo also thought most Arabic astrology was wrong, saying it "corrupted" Ptolemy's old astrology book Tetrabiblos. He wanted to bring back Ptolemy's original astrology.

Natural, Preternatural, and Supernatural

Many of Ciruelo's ideas about astrology were based on his religious beliefs. These are explained in his Reprobación de supersticiones y hechizerías. In the 16th century, studying astrology was a big religious debate. Any astrological practice that tried to do things beyond human power was seen as interfering with God's domain, which was considered heresy (a belief against church teachings). So, it was very important for astrologers to define what was humanly possible and what was divine.

In the 16th century, Christians believed in three ways things could happen: the natural, preternatural, and supernatural orders. Ciruelo explained these from a universe (cosmological) point of view:

- The supernatural order means events caused by God, like miracles. Ciruelo said it "comes from God, who operates miraculously on the course of nature."

- The preternatural order means events caused by spirits, demons, and angels. These beings were created by God and had special powers, but were still seen as natural beings. This mix of natural and supernatural created a middle ground: the preternatural.

- The natural order means events caused by things on Earth. Ciruelo said this usually involves actions by living creatures with free will.

Ciruelo believed these three orders were enough to explain everything on Earth. The natural and supernatural orders were first suggested by Anselm of Canterbury. Ciruelo added the preternatural order, seeing it as a natural result of the other two. This extra difference between the natural and the supernatural showed, in Ciruelo's view, that superstitious rituals were pointless. Rituals trying to do preternatural things could never work without help from a preternatural or supernatural power.

Because of these reasons, Ciruelo only thought "natural astrology" was "legitimate." This meant astrological practices that respected the line between the natural and the preternatural.

See also

In Spanish: Pedro Ciruelo para niños

In Spanish: Pedro Ciruelo para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |