Thomas Bradwardine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thomas Bradwardine |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

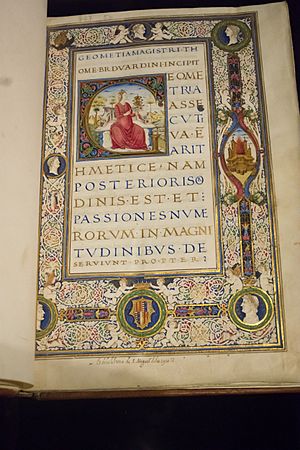

Codex in Latin with the work Geometria speculativa, illustrated by Cola Rapino's workshop (1495)

|

|

| Appointed | 4 June 1349 |

| Reign ended | 26 August 1349 |

| Predecessor | John de Ufford |

| Successor | Simon Islip |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 19 July 1349 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1300 Chichester or Hartfield |

| Died | 26 August 1349 Canterbury |

| Buried | Canterbury |

| Education | Merton College, Oxford |

Thomas Bradwardine (born around 1300 – died August 26, 1349) was an important English scholar. He was a cleric (a religious leader), a brilliant mathematician, and a physicist. He also worked for the king and, for a short time, became the Archbishop of Canterbury, a very high position in the church. People called him Doctor Profundus, which means "the Profound Doctor," because he was so smart.

Contents

Life of Thomas Bradwardine

Thomas Bradwardine was born in Sussex, England, sometime between 1290 and 1300. His family was part of the local gentry or townspeople. He might have been born in Hartfield or Chichester.

Early Education and Career

Bradwardine was a very bright student. He studied at Balliol College, Oxford, and later became a Fellow (a senior member) at Merton College, Oxford. He earned several degrees, including a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) by 1321 and a Doctor of Theology (D.Th.) by 1348. He was known for being a deep thinker, a skilled mathematician, and a clever theologian. He was also good at logic, especially with tricky problems like the liar paradox.

After his time at Merton College, Bradwardine took on important roles in the church. He became a Canon (a type of priest) in Lincoln in 1333. In 1337, he became the chaplain of St Paul's Cathedral in London.

Working with the King

Thomas Bradwardine became a close advisor to King Edward III. He served as the king's chaplain and confessor (someone the king would talk to about spiritual matters). He even traveled with the king during his wars in France. Bradwardine was present at the Battle of Crécy and the siege of Calais. The king trusted him with important diplomatic missions.

Archbishop and Death

In 1349, the church leaders in Canterbury chose Bradwardine to be the new Archbishop. However, King Edward III first wanted his own chancellor, John de Ufford, for the role. But Ufford died from the Black Death (a terrible plague) in May 1349.

So, Bradwardine traveled to Avignon to get approval from Pope Clement VI. Sadly, on his way back to England, he also caught the Black Death. He died in Rochester on August 26, 1349, just 40 days after becoming Archbishop. He was buried in Canterbury.

Bradwardine's Ideas

Bradwardine helped bring back ideas from Augustine, an ancient Christian thinker, during his time. He wrote about many subjects, including math, geometry, and how the human mind remembers things.

He also had strong beliefs about predestination, the idea that God has already decided everything that will happen. Bradwardine believed that even human actions, including evil ones, happen because of God's will. He thought that people couldn't do good things on their own, but only through God's plan. However, he also believed that free will (the ability to make your own choices) and predestination could exist together, all according to God's will.

The famous writer Chaucer even mentioned Bradwardine in his book The Nun's Priest's Tale, putting him in the same group as great thinkers like Augustine.

Bradwardine's Contributions to Science

Merton College, Oxford, where Bradwardine studied, was home to a group of smart scholars. They focused on natural science, especially physics, astronomy, and mathematics. These scholars were known as the Oxford Calculators. Bradwardine was one of them, working alongside others like William Heytesbury.

Understanding Motion

The Oxford Calculators studied how things move. They looked at kinematics (how things move) and dynamics (why things move). They were especially interested in how fast something moves at any exact moment.

They were the first to come up with the mean speed theorem. This theorem explains that if an object speeds up at a steady rate, it will travel the same distance as an object moving at a constant speed, if that constant speed is half of the accelerating object's final speed. They proved this idea long before Galileo, who often gets credit for it today.

A famous historian of science, Clifford Truesdell, said that the Oxford Calculators discovered and proved these ideas about motion. He noted that they changed how science worked by using numbers to describe movement, which is still how we do it today. Their work quickly spread across Europe.

Mathematics and Physics

In his book Tractatus de proportionibus (written in 1328), Bradwardine expanded on older ideas about proportions. He even came close to understanding the idea of exponential growth, which is used today to describe things like compound interest.

Bradwardine also tried to fix problems in Aristotle's ideas about how the physical world works. He disagreed with some common beliefs about how power, resistance, and speed are connected in motion. He looked closely at how ratios work.

He found a mistake in Aristotle's law of motion. Bradwardine's discovery was a big step towards modern physics. He was the first person credited with using exponential functions to try and explain the laws of motion.

Bradwardine's work also included some basics of trigonometry that he learned from Muslim scholars. However, he and his colleagues at Oxford didn't quite make the leap to what we call modern science, partly because they didn't have calculus yet.

The Art of Memory

Bradwardine was also interested in the "art of memory." This was a set of techniques used to help people remember things better and organize their thoughts. His book De Memoria Artificiali (around 1335) talked about memory training methods used in his time.

His work on memory was similar to ideas from the ancient Roman speaker Cicero. Bradwardine described detailed ways to remember specific information. He suggested using vivid, colorful, and active mental images, grouped into a series of "pictures" or scenes. These mental images helped recall not just facts but also how they were connected.

Bradwardine's Legacy

Thomas Bradwardine's ideas had a lasting impact. His theories about logical problems, like the liar paradox, greatly influenced the work of Jean Buridan, another important scholar. Bradwardine's work on how things move also influenced Buridan.

Even though he never left the Catholic Church, some of Bradwardine's theological ideas were similar to those that would later be part of the Reformation, led by figures like Luther and Calvin. His book De Causa Dei especially influenced John Wycliffe's ideas about grace and predestination.

Images for kids

-

Codex in Latin with the work Geometria speculativa, illustrated by Cola Rapino's workshop (1495)

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Bradwardine para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Bradwardine para niños

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |