Penutian languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Penutian |

|

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

North America |

| Linguistic classification: | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions: |

Takelma †

|

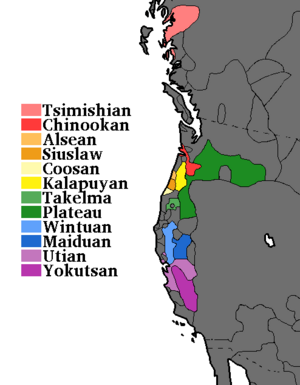

Pre-contact distribution of proposed Penutian languages.

|

|

|

|

Penutian is a suggested group of language families. It includes many Native American languages. These languages were once spoken in western North America. This area covers parts of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.

Experts still debate if the Penutian language group truly exists. Some parts of the group are also debated. It's hard to study these languages because many died out early. Also, there isn't much information written down about them.

However, some newer ideas about Penutian subgroups have strong evidence. For example, the Miwokan and Costanoan languages are now grouped as Utian. This was shown by Catherine Callaghan. She also found evidence that Utian and Yokutsan languages belong together in a Yok-Utian family.

There is also good evidence for the Plateau Penutian group. This group includes Klamath–Modoc, Molala, and the Sahaptian languages. The Sahaptian languages are Nez Percé and Sahaptin.

Contents

History of the Penutian Idea

What "Penutian" Means

The name Penutian comes from words meaning "two" in several languages. These include the Wintuan, Maiduan, and Yokutsan languages. The word for "two" in these languages sounds like "pen." In the Utian languages, it sounds like "uti."

Most language experts say "Penutian" like "pih-NYOO-shun."

Early Ideas: Five Core Families

The first idea for Penutian came in 1913. Roland B. Dixon and Alfred L. Kroeber noticed similarities. They saw these links between five language families in California:

This first idea is sometimes called Core Penutian or California Penutian. Dixon and Kroeber published their findings in 1919. Their grouping was based on how languages were built, not always on shared history. Because of this, the Penutian idea was debated from the start.

Before 1913, Albert S. Gatschet had already grouped Miwokan and Costanoan. This group is now called Utian. It was later proven by Catherine Callaghan.

Sapir's Bigger Picture

In 1916, Edward Sapir added more languages to the Penutian family. He created a new branch called Oregon Penutian. This branch included the Coosan languages, plus Siuslaw and Takelma.

Later, Sapir and Leo Frachtenberg added more groups. They included the Kalapuyan and Chinookan languages. They also added the Alsean and Tsimshianic families.

By 1929, Sapir's ideas included six main branches:

- California Penutian

- Oregon Penutian

- Chinookan

- Tsimshianic

- Plateau Penutian

- Mexican Penutian

More Recent Ideas

Some other experts have suggested adding more languages to the Penutian group. For example, Benjamin Whorf proposed a "Macro-Penutian" idea. Joseph Greenberg suggested a link between Penutian and even larger groups like the Amerind family.

Some linguists once linked the Penutian idea to the Zuni language. However, this idea is generally not accepted today.

Doubts in the Mid-1900s

In the middle of the 20th century, some scholars worried about the Penutian idea. They thought that similarities between languages might be from borrowing words. This happens when neighboring groups share words. It doesn't mean the languages came from a single older language.

Mary Haas, a linguist, explained this concern. She said it's hard to tell if similarities are from shared history or from borrowing. She stressed that studying how words spread between groups is as important as studying their family tree.

Despite these worries, a meeting in 1964 kept all of Sapir's North American groups within Penutian. But at a 1976 meeting, experts decided that the Penutian group was not yet fully proven.

Newer Ideas and Support

In 1994, a workshop at the University of Oregon found some agreement. Experts thought that the California, Oregon, Plateau, and Chinookan groups would likely be shown to be related. Later, Marie-Lucie Tarpent studied Tsimshianic. This family is far away in British Columbia. She concluded it also likely belongs to Penutian.

Some older groupings, like California Penutian, are no longer accepted by many researchers. However, other groups are gaining more support. These include Plateau Penutian, Coast Oregon Penutian, and Yok-Utian. Yok-Utian includes the Utian and Yokutsan languages.

Scott DeLancey has suggested some relationships within the Penutian family:

- Maritime Penutian

- Inland Penutian

- Yok-Utian (from the Great Basin)

- Maidu (from the Great Basin or Oregon)

- Plateau Penutian

The Wintuan languages, Takelma, and Kalapuya are still seen as Penutian languages by most scholars. They are often placed in an Oregonian branch.

Proof for the Penutian Idea

It is hard to rebuild the original sounds of Penutian languages. This is because many Penutian languages change their vowels. However, consonant sounds often match up.

For example, certain sounds in Proto-Yokuts (an early Inland Penutian language) match different sounds in Klamath (a Plateau Penutian language). This shows a pattern. But other languages like Kalapuya, Takelma, and Wintu do not show such clear links.

Here are some sound matches suggested by William Shipley. They show how sounds in an older "Proto-Penutian" language might have changed into sounds in newer languages.

-

- California Penutian and Klamath Sound Matches

| Suggested Proto-Penutian |

Klamath | Maidu | Wintu | Patwin | Yokuts | Miwok | Costanoan (Ohlone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'p, 'ph | p, ph | p | p, ph | p, ph | p, ph | p | p |

| **k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k |

| 'q, 'qh | q, qh | k | q | k | x (-k) | k | k |

| **m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| **n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| **w | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- |

| (l) | -l- | -l- | -l-, -l | -l-, -l | -l- | -l- | -l-. -r |

| #**r | s[C, L[V | h | tl, s | tl | ṭh | n | l, r |

| **-r- | d, l | d | (r?) | r | ṭh | (n?) | r |

| **-r | ʔ | ʔ | r | r | ṭh | n | r |

| **s | s- | s- | s- | s- |

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas penutíes para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas penutíes para niños

- Hokan languages

- Macro-Mayan languages

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |